—

exhibition Details

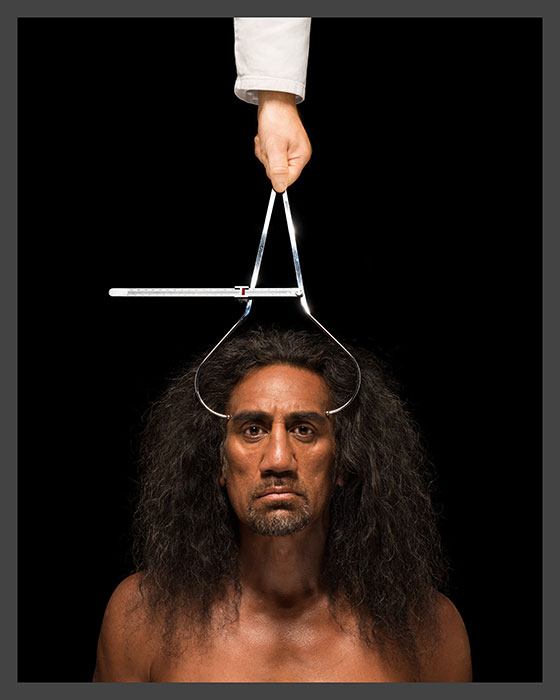

Storytelling, Pacific histories and politics are powerful drivers in the artwork of John Pule and Yuki Kihara. Follow the arresting narrative in Pule’s 18-part drawing Death of a God, which offers an account of anthropologist Dr Edwin Loeb’s early 20th-century fieldwork in Niue, and see Kihara’s clever critique of the pseudo-science of anthropometry – the measurement of the human individual – in her photographic series, A Study of a Samoan Savage.

Yuki Kihara

Yuki Kihara artist concept outline. Courtesy of the artist and Milford Galleries Dunedin

The five works from Yuki Kihara’s 2015 series A Study of a Samoan Savage show a man as a manifestation of the Pacific demi-god Maui, being examined. The images show the use of medical instruments in the human body’s evaluation and reference the role of photography in 19th-century scientific and pseudo-scientific analysis. In Kihara’s estimation, Samoan men were historically depicted as ‘exotic savages, fetishized as a subject and as an object, colonised and treated as commodities’.

As background to this series Kihara studied the historical European use of anthropometry as a tool in social anthropology. Anthropometry involves ‘taking the measure of a man’ and is a pseudo-science encountered in cross-cultural studies of non-Western people. The practice involved the hierarchical evaluation of race based on body shape and skin colour. Early anthropologists used photography to collect information about ‘body types’, which they then employed to propound scientific theories, including racial eugenics or the supposed genetic improvement of the human race.

A Study of a Samoan Savage is both an indictment of the stereotyping of anthropometry and a re-presentation of its methodologies. Maui’s expression connotes a sense of old-fashioned stillness in posing for a studio portrait. Yet he also looks defiant, which issues a challenge that strongly contrasts the historical ways such subjects were depicted. Through taking control of the camera and representation, this artwork conveys a provocative message by reusing a historical method of cultural categorisation to critique and rebut racial bias.

Ko ngā rima t oi i tā Yuki Kihara rārangi o 2015 He tirohanga o He Tauira tangata Mohoao Hamoa e āhua tangata ana, ko te korokē ko Māui kei te tirohia. Ko nga toi e whakaahua ana i ngā taonga rongoa i roto i te tinana tangata, e tātari e pā atu ana ki te mahi a te toi whakaahua i ngā rau tau mai i 1900 hei whakatauira i te mahi pūtaiao tika, kore mana rānei. I tā Yuki Kihara whakatau, i tohungia i aua wā ko ngā tāne Hāmoa he mohoao tino rerekē, whakamana nuitia hei tauira, hei taonga, kua pūreitia, kua whakamaimoatia he mea noa iho.

Hei pātū mō tēnei rārangi toi, i ako a Kihara i te mahi ‘anthropometry’ he kaitaki mātauranga i te akoranga take tika tangata. ‘Anthropometry’ ko te mahi whātau tangata, he mahi koretake e mau ana i ngā tirohanga e whakariterite ana, whakarerekē rānei, i ngā iwi taketake o mua, Ko tana kaupapa he whakarārangi i te mana o ia momo taketake mai i ōna āhua tinana, ā, tae kiri hoki. Ko ngā kaikohi whātau tangata o mua i whakamahi i te tango whakaahua hei kohikohi i ngā momo tinana, ka whakamahia hei hanga aro pūtaiao, tau atu ki te āhua momo rerekētanga ā-iwi, me te tupu pai haere ake koia o te āhua momo tangata.

He tauira tangata mohoao Hāmoa – E rua ōna tohu kino, ko te mahi whakamana nui i te mahi ‘anthropometry’ me te whakaora ake i ōna momo mahi. Ko te āhua o Māui e whai ana i te nuku kore tawhito o mua i te noho ki te tangohanga whakaahua. Ahakoa rā, he āhua riri anō ka kitea, tino rerekē ki te āhua tawhito kei aua hunga kua whakaahuatia i mua. Mā te kapo i te mana o te pouaka whakaahua, me tana whakatau mai, ka takina e tēnei momo toi te tono tumatuma mā roto i te whakahou i te momo mahi tawhito e whakarārangi momo tikanga me te patuki tirohanga whakaiti momo iwi.

John Pule

John Pule once noted that his work aimed to ‘recreate the knowledge lost in migration’. He does this with an art practice that involves a variety of media – literary novels, poetry, installation, performance, painting, drawing and print-making. Pule’s achievements with these art forms, created over three decades, has gained him an international reputation.

All of Pule’s artwork generates composite visual, written and spoken narratives. He weaves politics, cosmology and mythology together, and pictures global shifts in time and place. Increasingly, Pule’s work acts like a cartography of human relationships while responding to history’s inextricable connection with personal memory. He frequently juxtaposes Pacific cultures with the influence of depopulation and diaspora.

John Pule’s art is informed by a wide-ranging familiarity with anthropological accounts of Niue’s culture. His 1998 novel Burn My Head in Heaven (Tugi e Ulu haaku he Langi) is an indigenous narrative about the seven months of anthropological fieldwork that American scholar Dr Edwin Loeb undertook on Niue during 1923–4.

In 1999, Pule further expanded his account of Loeb’s controversial study of Niuean culture by illustrating it in the 18-part drawing that he titled Death of a God. Loeb’s published research includes an account of Niueans recreating their historic killing-the-god ritual. They made an effigy of the god Limanua, which was included in a performance event that Loeb witnessed and participated in. John Pule’s visual narrative mixes pictographic drawings with his own report to give an account of the anthropologist’s involvement in an ancient Niuean ritual.

E ai ki ngā whakatau a John Pule i mua, ko āna mahi e hāngai ana ‘ki te hanga i te mātauranga i ngaro whakatere’. Ka mahia ēnei e ngā mahi toi e mau ana i ngā momo pāpahō – tuhinga pukapuka, mahi whiti, rauhanga, whakatau, toi kokowai, whakaahua, tānga kahu. Ko ngā rerenga o aua mahi toi, neke atu te hanganga i te toru tekau tau, i whakanuitia ai tōna mana i te ao whānui.

Ko te katoa o ngā mahi toi a Pule ka hono tahi i ngā wānanga tirohanga, tuhituhi, me te whakatau kupu. Ka rarangatia e ia te ao tōrangapū ki te ao tuku iho me te ao pūrākau – me te neke whānui o te ao i waenga wā me waenga wāhi. E ai ka māhi ngā hanganga a Pule pēnei i te pūrewa whakapapa i waenga i te whakautu ki te hono tūturu o te whakaheke tātai ki te hinengaro. Ka taurimatia e ia ngā tikanga Moana Marino ki te pānga o te mimititanga me te whakatere hunga tāngata.

Kia whāngaia ngā mahi toi a John Pule e tōna mātauranga whānui ki ngā hahunga tuhinga o te ao mengā tikanga o Niuē. Ko tana tuhinga pukapuka o 1998, Burn My Head in Heaven (Tugi e Uku haaku he Langi – Tahuna taku Upoko i te Rangi) he tuhinga māori mō te ono marama i kimi mātauranga ai te tohunga nei a Dr Edwin Loeb i Niue i ngā tau 1923–4.

I te tau 1999, ke whakawhānuitia e Pule ta na tuhinga mo te tirohanga rikarika nei a Loeb i ngā tikanga o Niuē, ka whakaahuatia e ia ki tana mahi toi 18 ōna wāhanga, i tohu te ingoa Te Matenga Atua. Ko te tuhinga a Loeb i tāngia he tuhinga nāna mo te ‘tikanga patu atua’ i mahia e rātou i Niuē. Nā rātou i mahi he āhua mō te atua, mo Limanua, ka whakaurua ki te kapa i kite, i uru atu a Loeb. Ko te toi whakaahua a John Pule e hono ana i ngā kōrero me ngā toi āhua o tana ake tuhinga o te hononga o te tohunga tikanga tangata ki ngā tikanga tawhito o Niuē.

- Date

- —

- Curated by

- Ron Brownson

- Location

- Ground level corridor

- Cost

- Free entry

Related artworks

A study of a Samoan Savage: Head with Pelvimeter

C-type print

Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, gift of the Patrons of the Auckland Art Gallery, 2015

A study of a Samoan Savage: Bicep with Skinfold Caliper

C-type print

Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, gift of the Patrons of the Auckland Art Gallery, 2015

A study of a Samoan Savage: Subscapular with Skinfold Caliper

C-type print

Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, gift of the Patrons of the Auckland Art Gallery, 2015

A study of a Samoan Savage: Nose Width with Vernier Caliper

C-type print

Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, gift of the Patrons of the Auckland Art Gallery, 2015

A study of a Samoan Savage: Subnasale-nasale Root Length with Vernier Caliper

C-type print

Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, gift of the Patrons of the Auckland Art Gallery, 2015