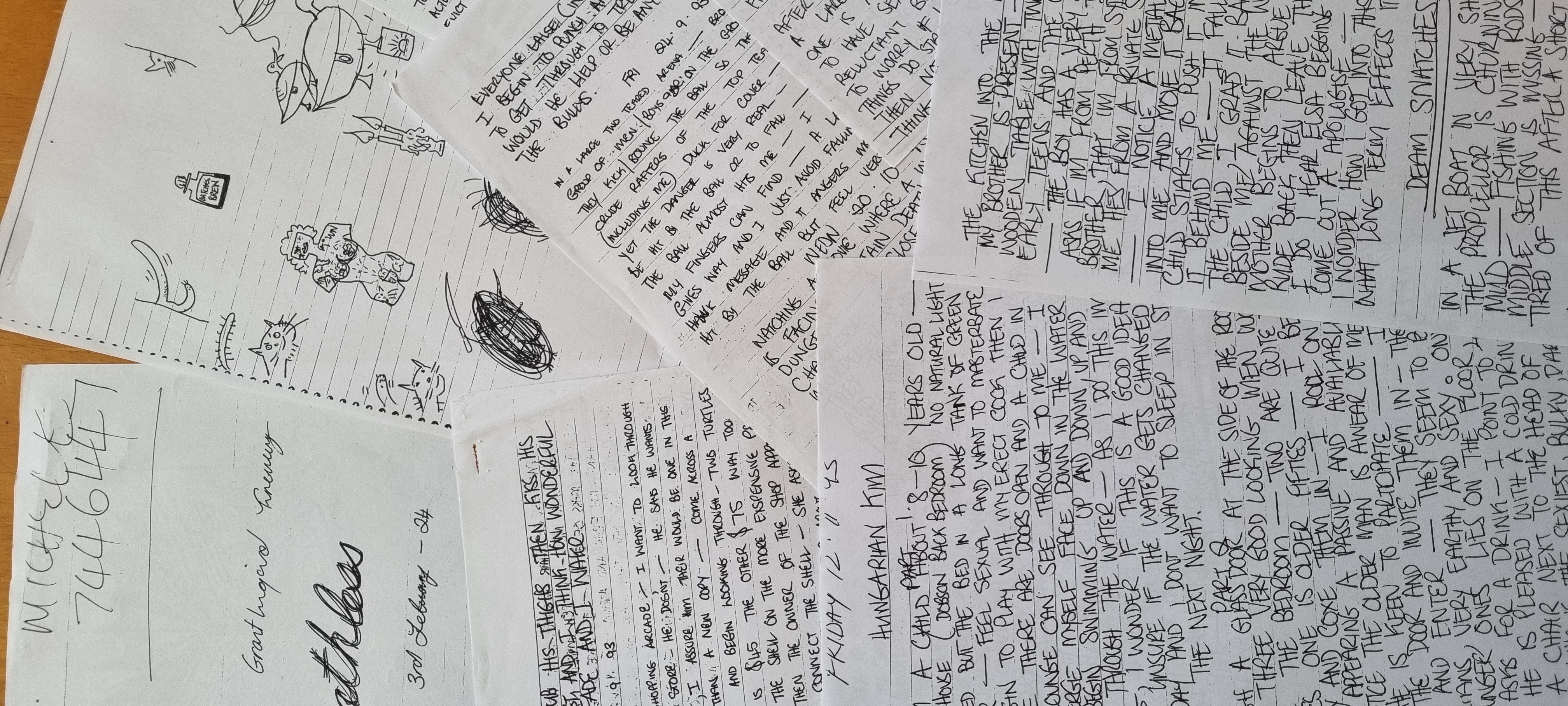

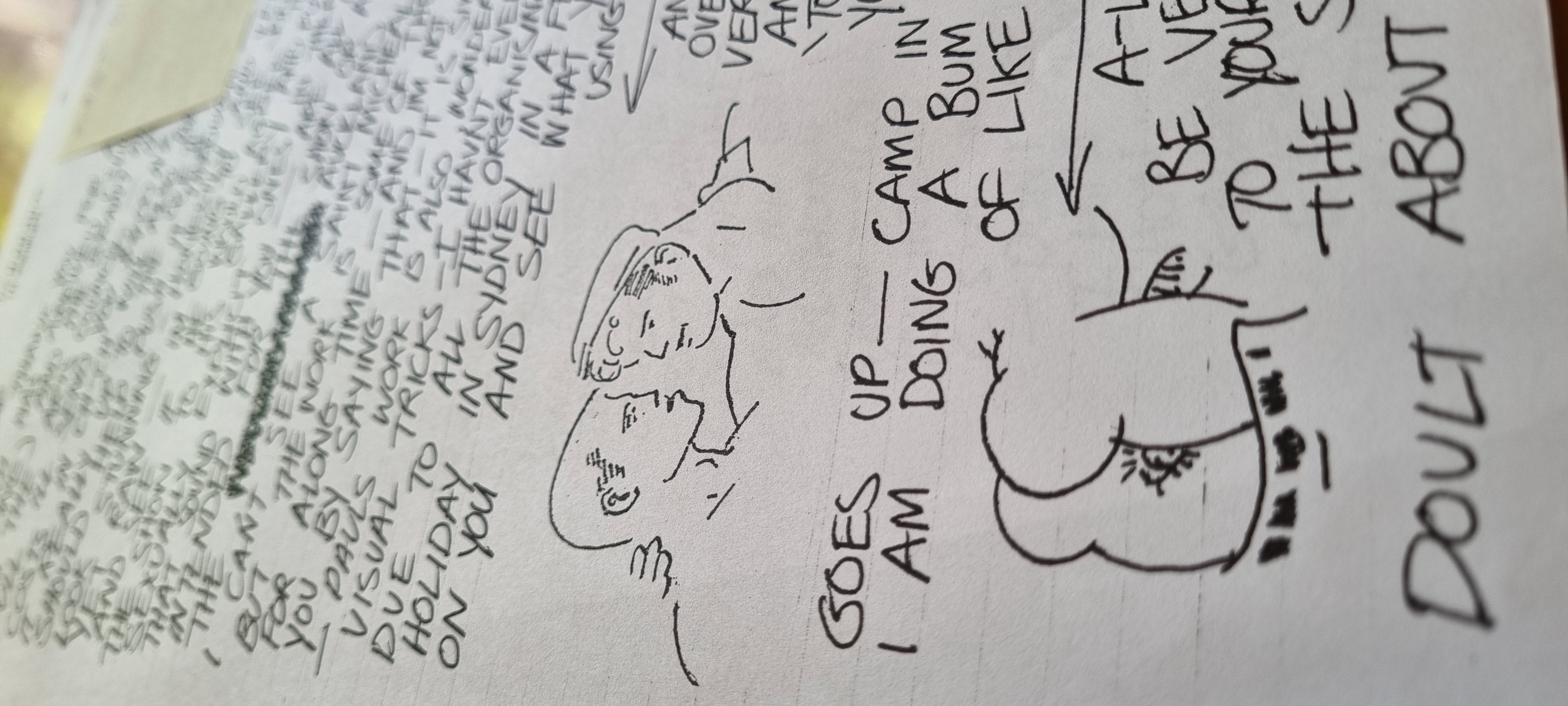

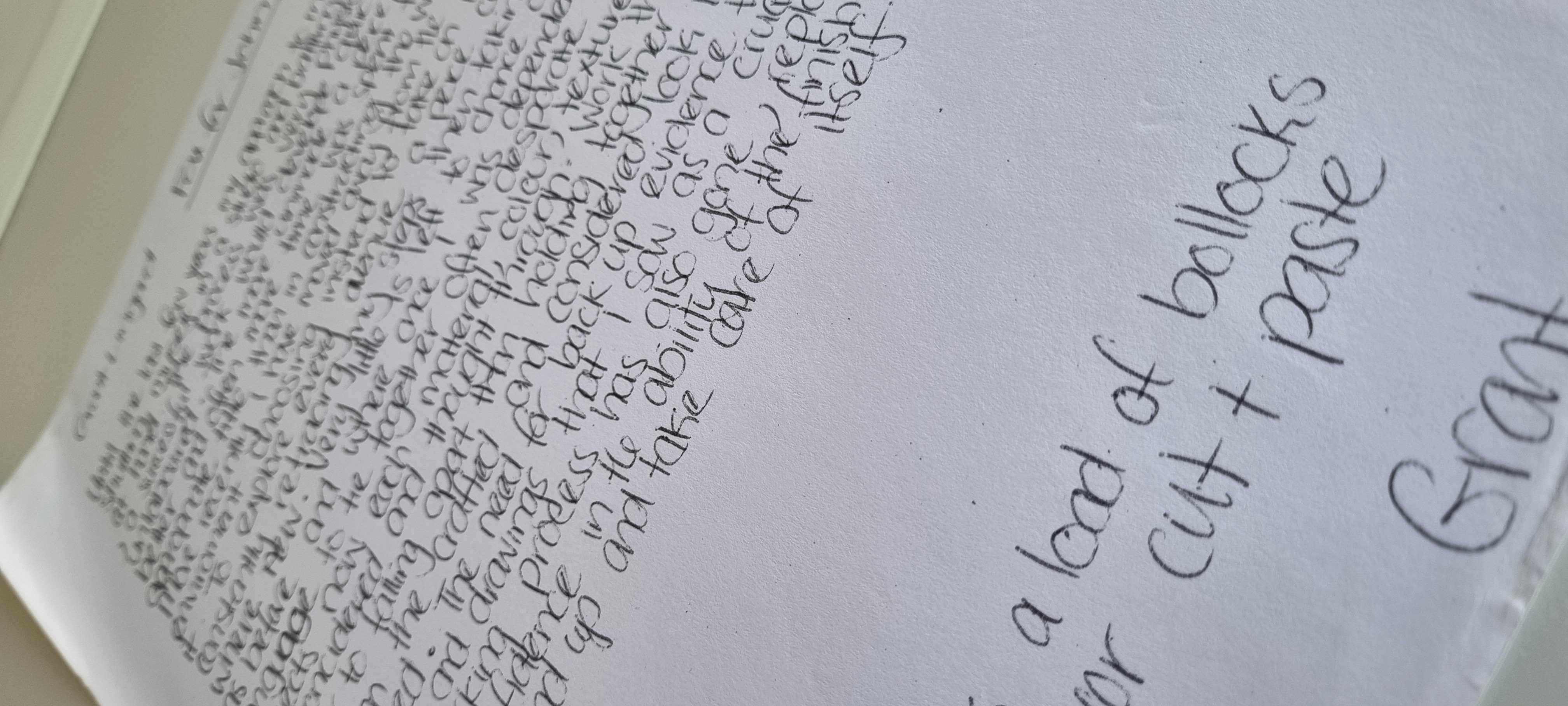

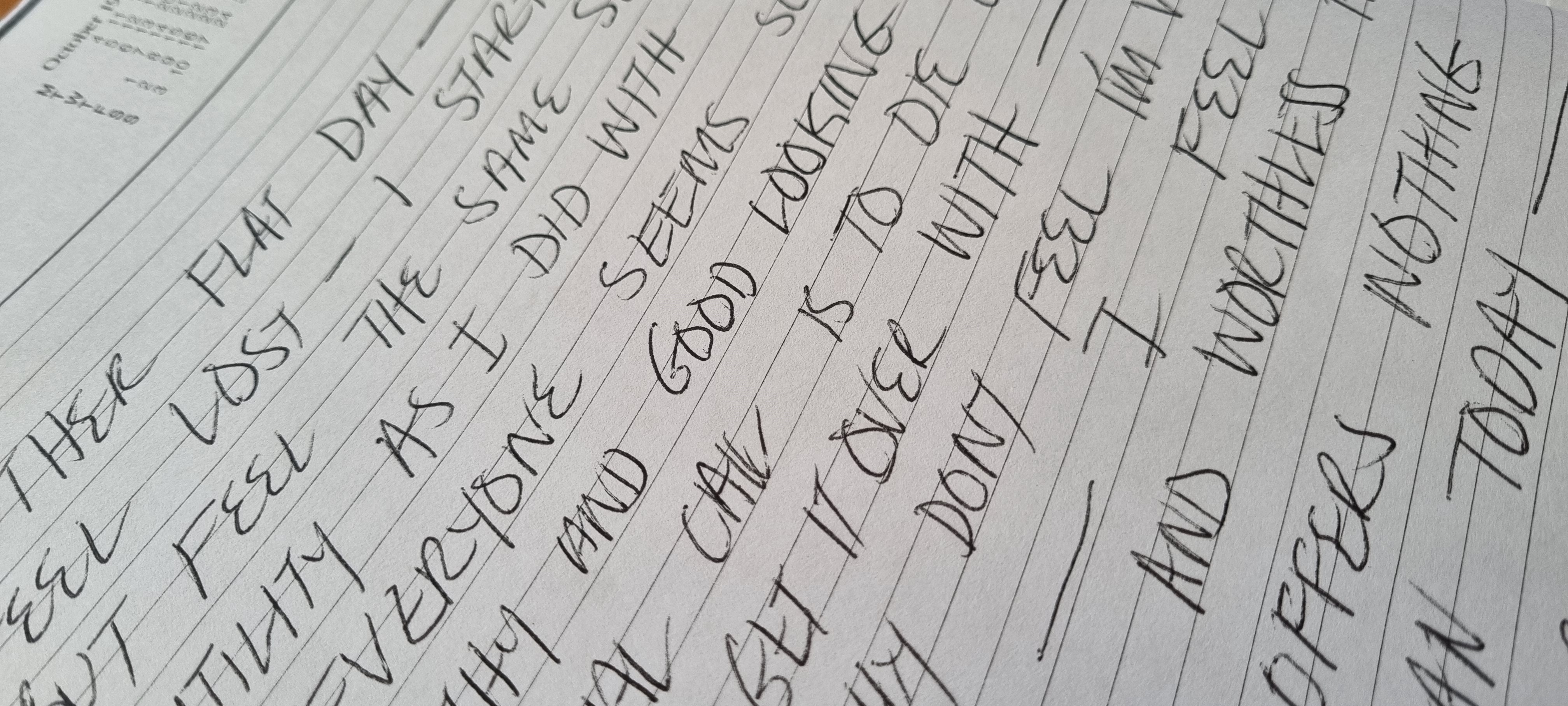

Grant Lingard (1961–1995) was a West Coast boy through and through. Born in the tiny town of Blackball (most famously known as the birthplace of the New Zealand Labour Party), he came from a line of coalmining, rugby-playing men, who were considered by many to be prototypes for the good Kiwi bloke. Practical men, manly men, tough men, emotionless men. Such ideals of manliness that could never be applied to Grant, but they were exactly what he based his creative practice on.

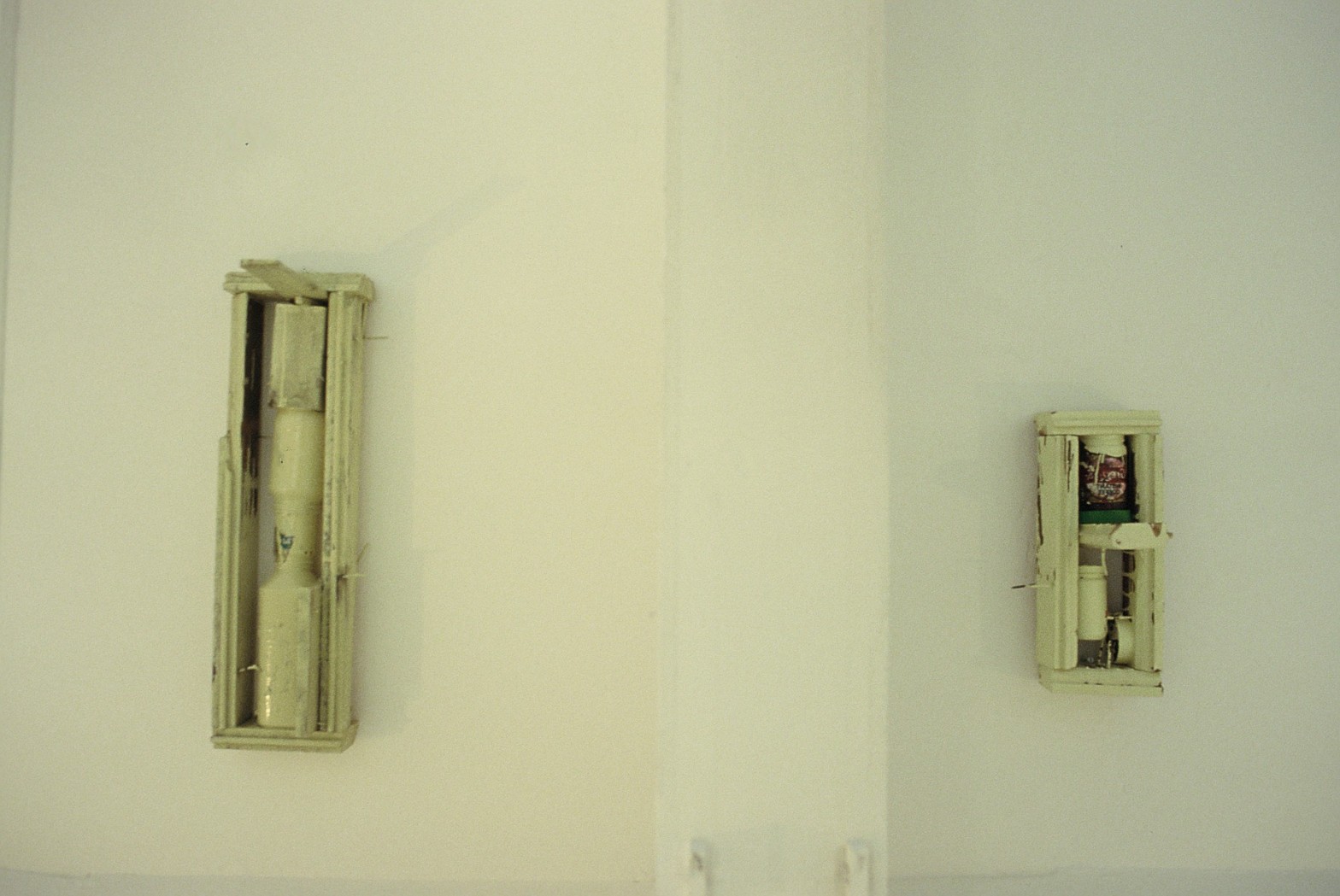

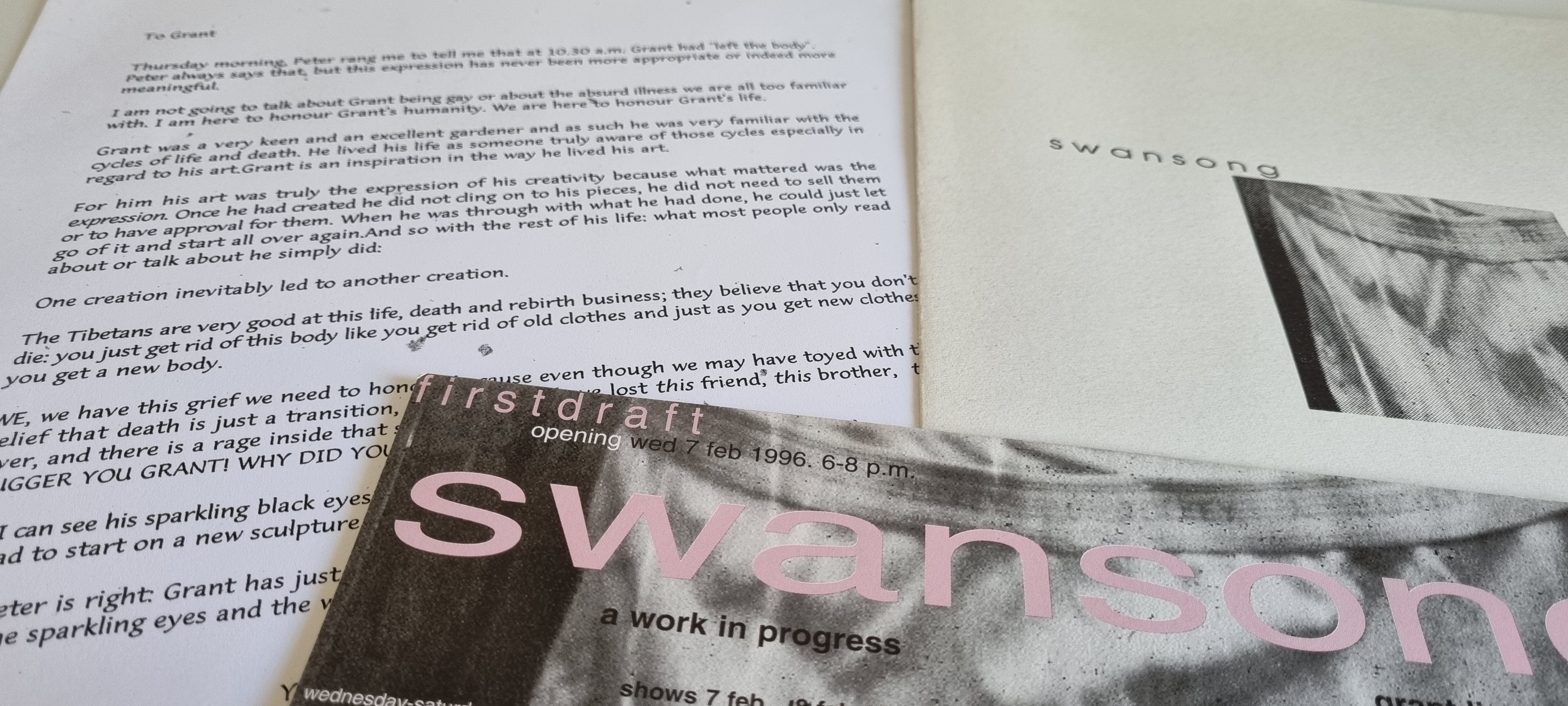

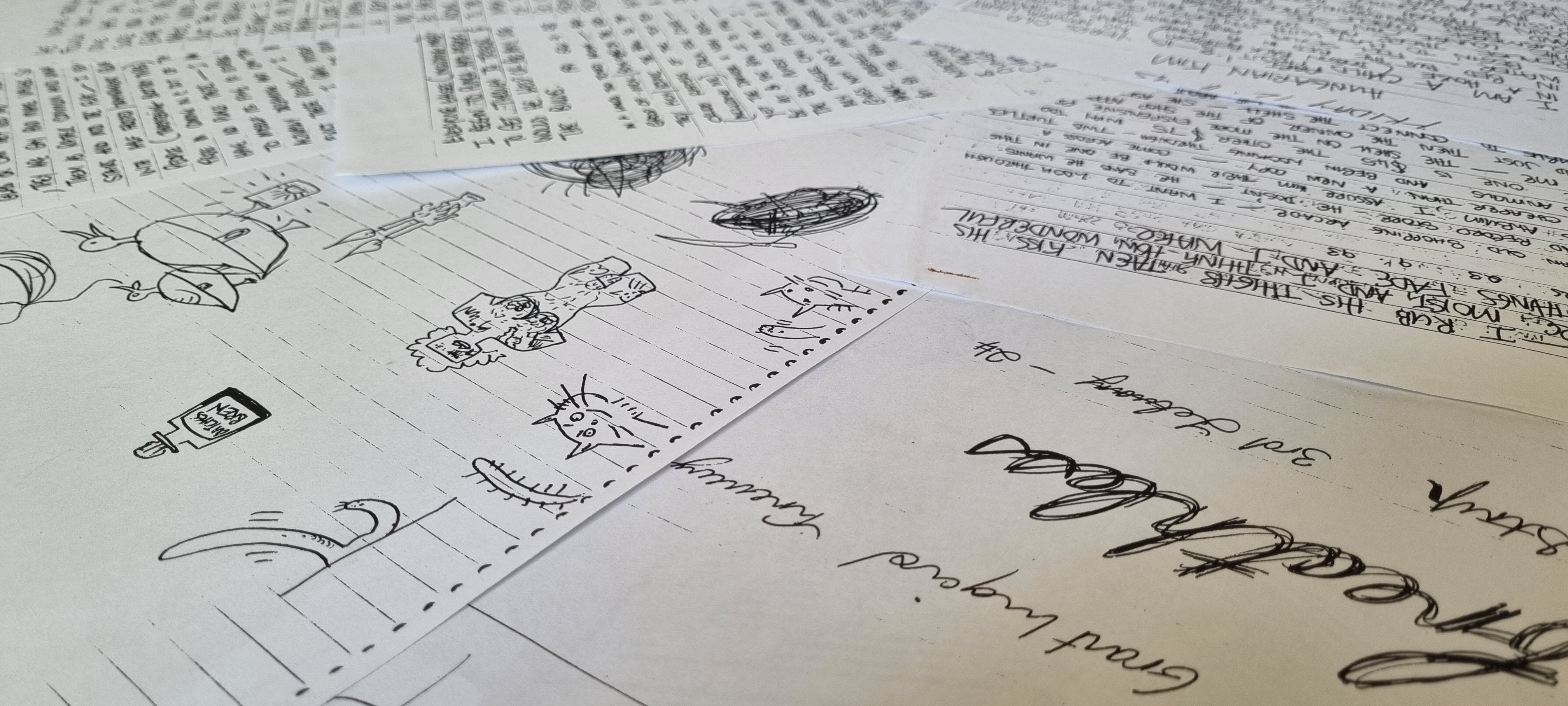

From State House Yellow (1 & 2), 1985, a homage to New Zealand’s public housing made from demolition materials to Strange Bedfellows (4 Flagons, 4 Poems), 1993, in which he installed flagons – the good-Kiwi-bloke staple – on gallery plinths, Grant’s work focused primarily on masculinities and his attempt to make sense of his own queerness. From 1987 onwards, his work took on an additional value, with Box of Birds (an image of which could be seen in the Malcolm Ross, Fiona Clark, Grant Lingard: Looking at Men display at Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, although it was never exhibited) which can be considered his first direct response to the AIDS crisis. This additional layer of ‘virus’ is clear, as his own diagnosis and health journey became more central to his work. Indeed, Swan song, an exhibition planned by Grant, was installed by his friends at Firstdraft in Sydney, Australia in 1996 after his death, and recently shown at the Adam Art Gallery Te Pātaka Toi.

Grant’s work traversed risqué topics: cruising in Christchurch’s Hagley Park (the exhibition Incident in the Park, 1988); homosexuality, in the group exhibition Homosexual: Beyond Four Straight Sides, 1988; the damaging and othering influence of rugby (the exhibition Smells Like Teen Spirit, 1993); the personal impact of HIV/AIDS (the 1991 exhibition Beauty and the Beast); and of course, Swan song.