In 2019, Gretchen Albrecht – Between Gesture and Geometry, published by Massey University Press, was launched at Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki. Written by Luke Smythe, it is a monograph of Gretchen Albrecht, whose dedicated practice has enriched and illuminated our country’s art for over 60 years.

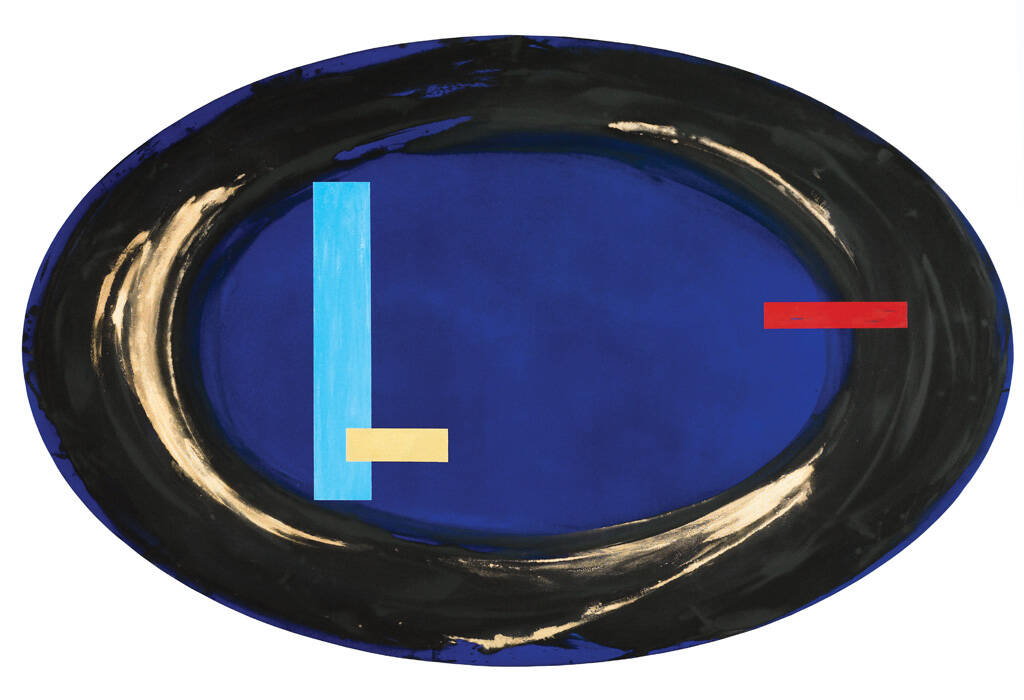

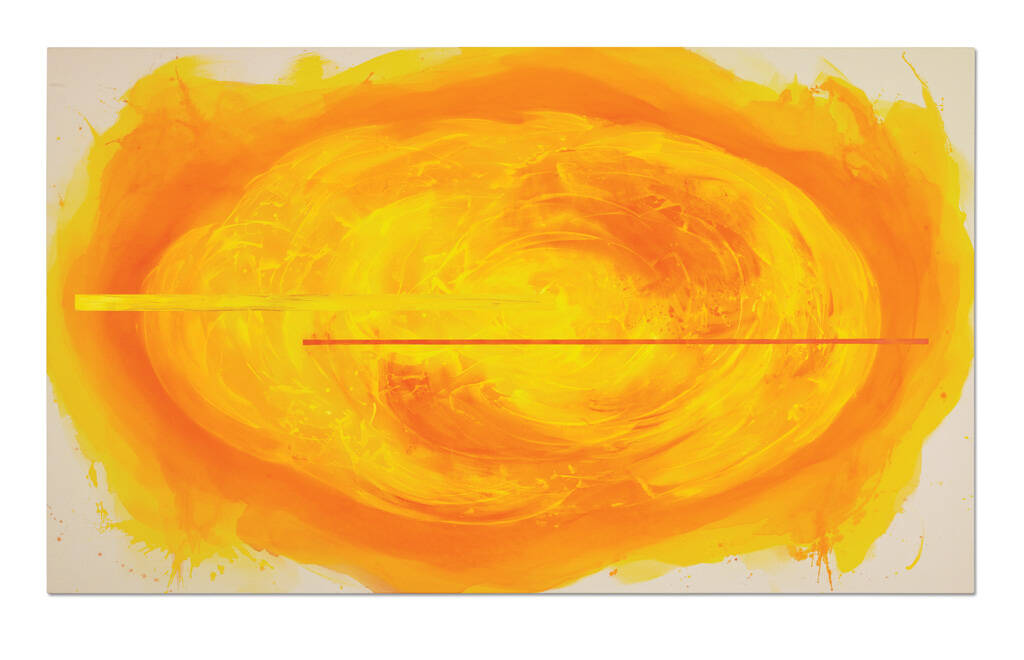

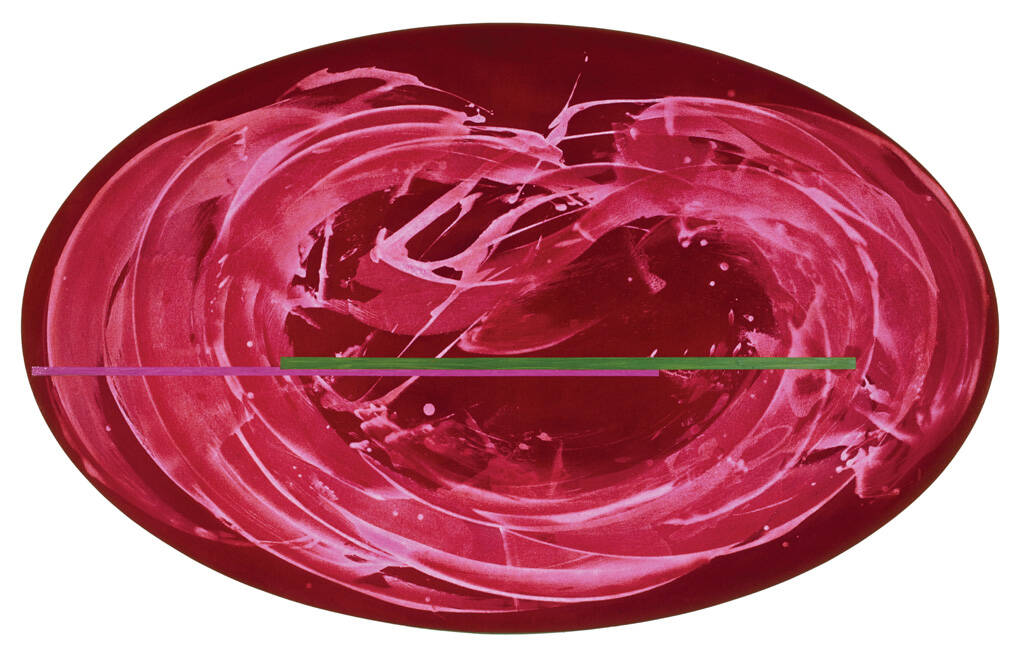

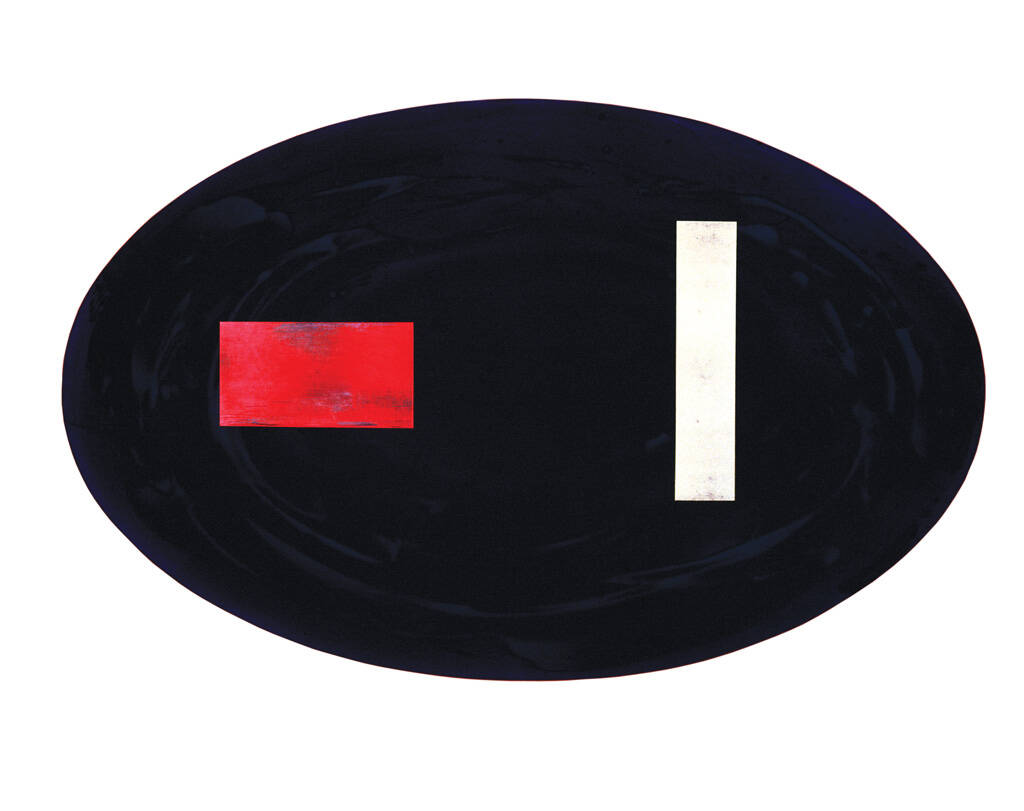

The Gallery holds at least seven of Albrecht’s major works, including Aotearoa – Cloud, 2002, and Gains and Losses (Father – Red), 1998, and has held two solo exhibitions over the years: Seasonal/Four Paintings (1985–86), and Gretchen Albrecht: Illuminations (2002).

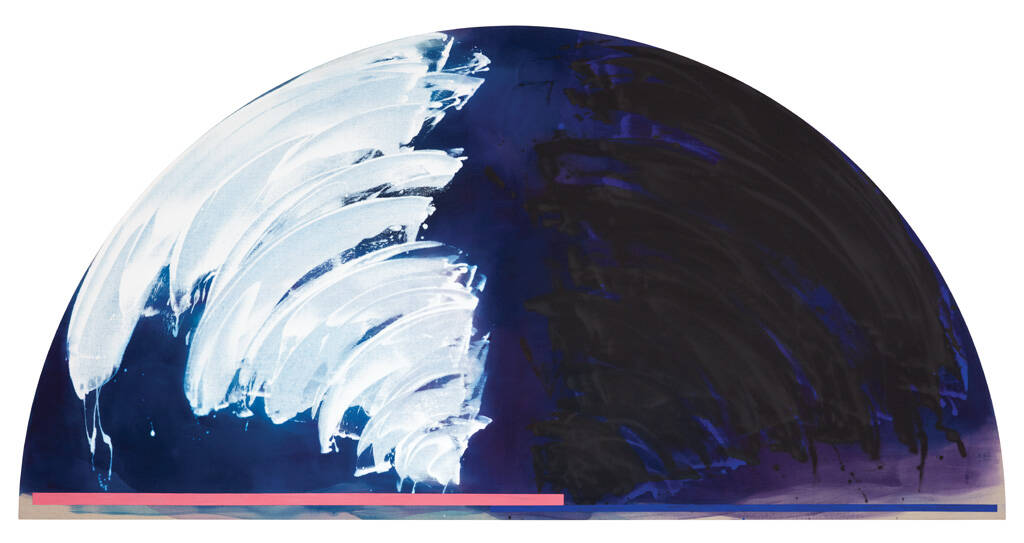

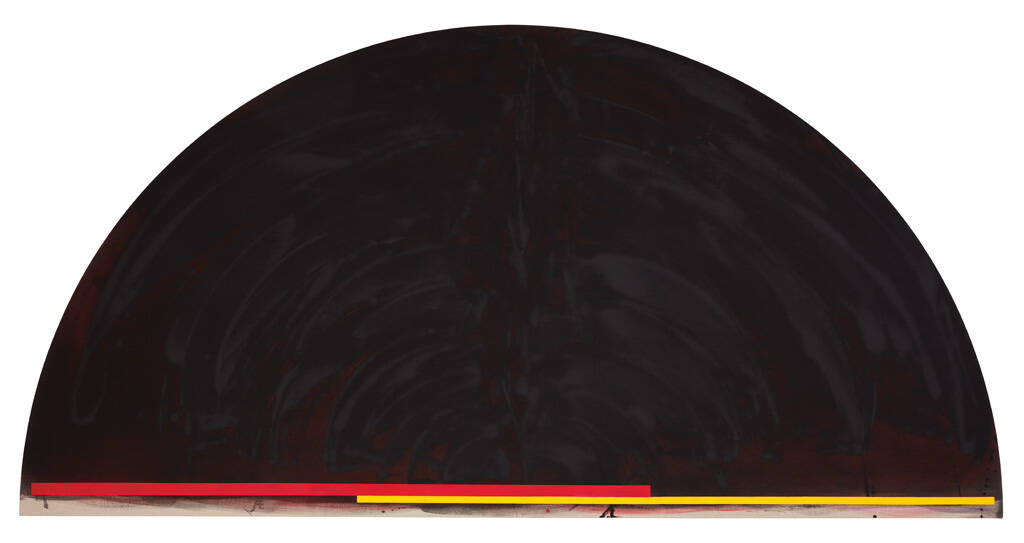

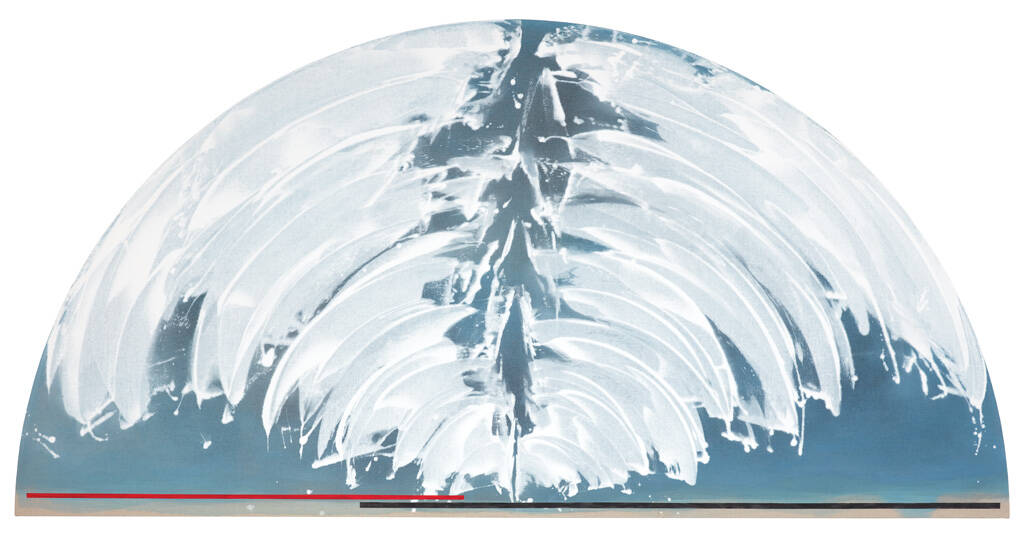

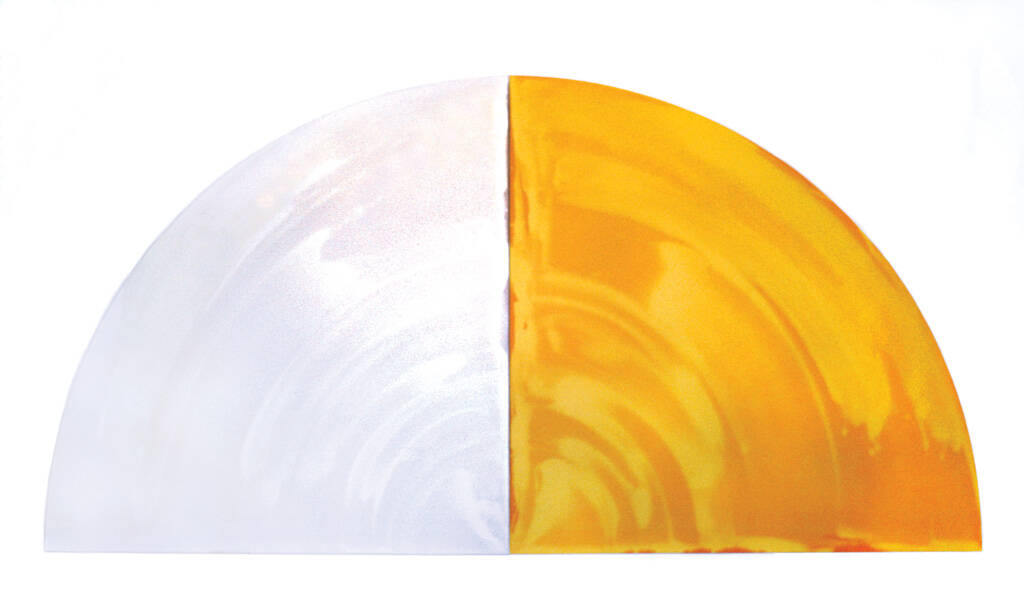

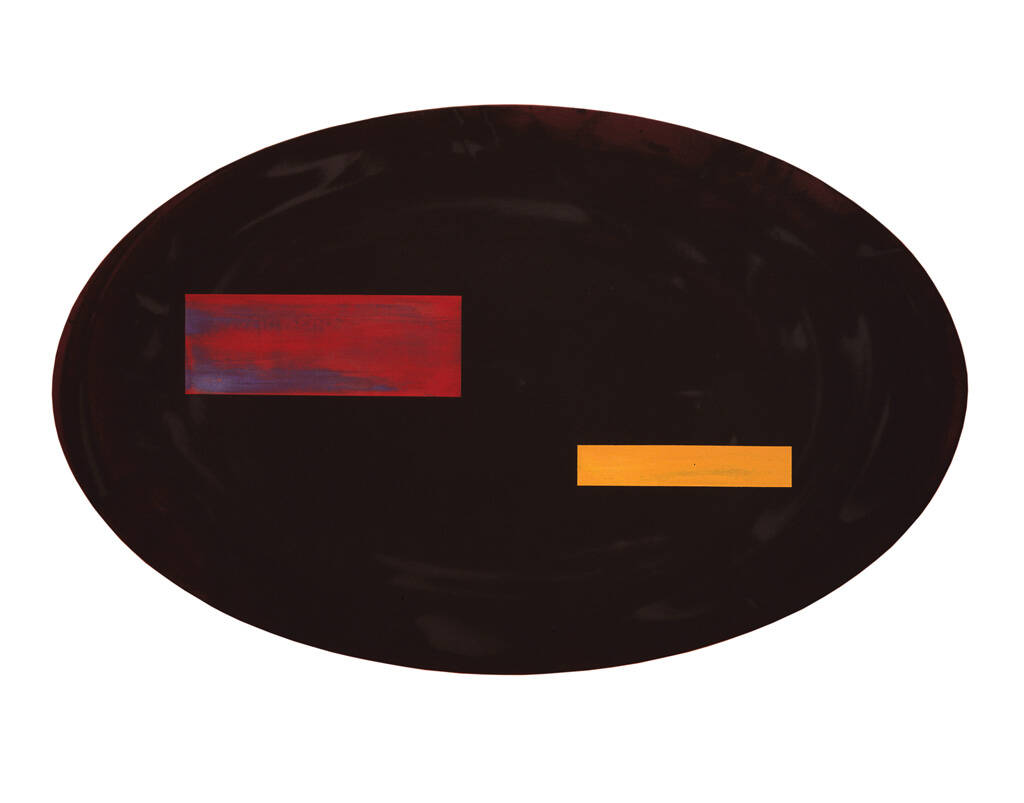

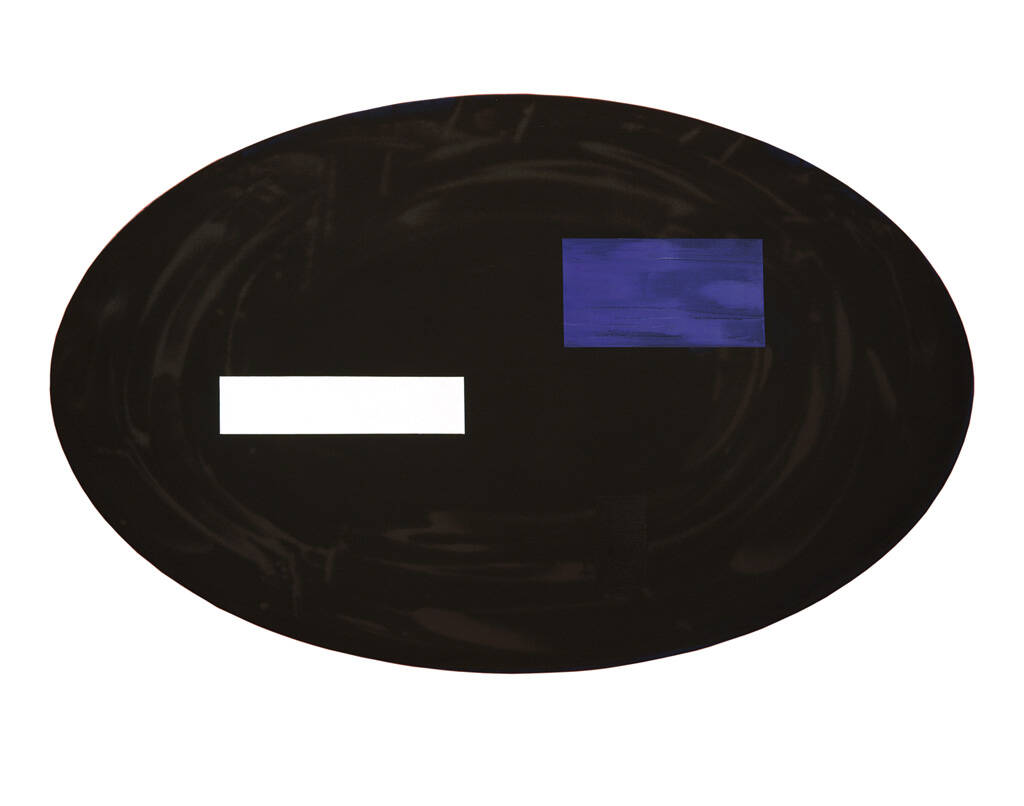

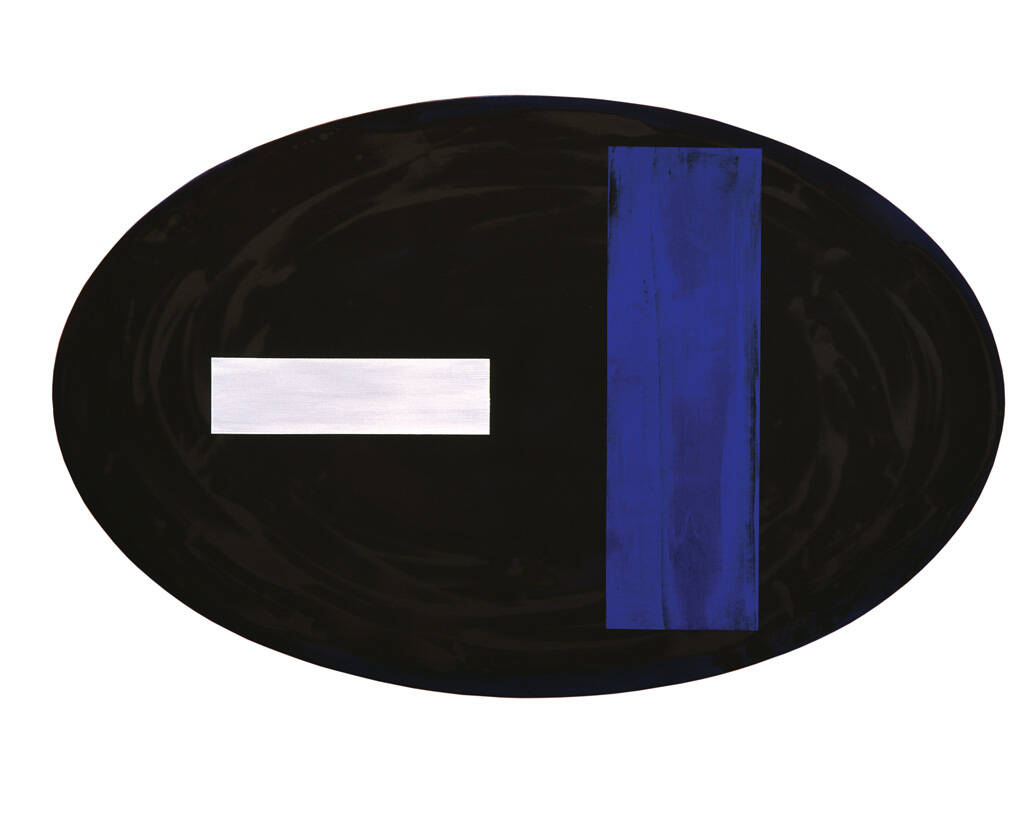

The Covid years, with their insistence on solitude and containment, prompted Gretchen to reconsider themes and structures in her work from the perspective of a painter with a long view. During those years, she completed two suites of paintings: After Goya, 2020, four large hemispheres ‘talking’ to four portraits by Goya, which reaffirmed her kinship with the Western art tradition, and Eight Hours, 2019–21, a meditation on the eight hours of the Divine Office, prayers sung throughout day and night in monasteries since medieval times which honour time’s eternal present.

The significance of these series was recognised by author and publisher, and in 2023, a revised edition of the monograph with a new cover and a final evocative chapter, ‘Time’s Measure’, was launched at Two Rooms Gallery.

Catharina van Bohemen spoke to Gretchen Albrecht about working with Luke Smythe, how she paints, and the importance of After Goya and Eight Hours.