—

exhibition Details

Winner

Finalists

International judge

Judge's statement

Jury

Jury's statement

Sponsors

Coordinating curator

Publication

Winner of the Walters Prize 2006

The Walters Prize 2006 was awarded to Francis Upritchard for Doomed, Doomed, All Doomed. The winner was announced by international judge, Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev at a gala dinner on 3 October 2006.

Finalists

- Wet Social Sculpture 2005, by Stella Brennan: first shown at ST PAUL St Gallery, Auckland

- Polar Projects 2004, by Phil Dadson: first shown at Dunedin Public Art Gallery

- The Humours 2005, by Peter Robinson: first shown at Dunedin Public Art Gallery

- Doomed, Doomed, All Doomed 2005, by Francis Upritchard: first shown at Artspace, Auckland

International judge

The Walters Prize 2006 was judged by Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, then Chief Curator at the Castello di Rivoli Museum of Contemporary Art in Turin. Christov-Bakargiev co-curated the first Turin Triennale, was the artistic director of the 2008 Sydney Biennale and was previously senior curator at New York's P.S.1 Contemporary Art Centre.

Judge's statement

I have selected Francis Upritchard for this prize. There is a mysterious conjuncture between the found materials and the 'made' parts of her work, as materials are transformed. Her works are not assemblages, nor collages. Rather, she transitions and recycles found and dead objects into forms of portraiture that posit discrete healing and mending of subjectivity. Leather returns to being the skin of a face or of the hands after the violence it has been through in the cycle of industrial production of leather. Fur goes back from being part of someone's fur coat to being hair on a body. And this return to the body of an animal, whether human or not, is poetic. Upritchard celebrates the hand-made, and poor technology seems to me increasingly topical today, in the digital age. To understand the past, one does not only collect it, one does not need to incorporate it into a museum or archive, one needs to remake it, to recreate it, and thus to make it personal and one's own. We have all been fascinated by old hair combs, sewing instruments, paper cutters.

But to make them again, not to find and appropriate them, is a delicate procedure, an unheroic procedure. There is a nostalgia and a yearning to make figures today, and Upritchard makes them, but at the same time she suggests how individual subjectivity is very vulnerable and fragile today: on a large plinth in the second gallery, there is a frontal display of four figures. They all point in a direction or have a tension towards somethings, either towards each other, towards us, or towards some spiritual entity, almost as if they were figures of a Pieta (a Deposition from the cross). They sit or stand or kneel on individual plinths on top of a white base, and look from the front, at first glance, as if they are full sculptures 'in the round', each alone and solitary. They are suffering, praying, needing, asking. But as you walk around them, to the back of the white base, they suddenly appear flat, like silhouettes, almost paper cut-outs. This sudden absence of depth is shocking, and perhaps suggests the false depth of consciousness today, in our age of global scanning. You then realize that this lack of depth in the world today, is underlined by the lay-out of the exhibition itself: an empty wall in the main gallery, while little sculptures hang around the corner, to the side, where labels would normally go, or on the floor, again in a corner area of the second room. Two left-over pieces of furniture are on another margin of the display area. And, back to the plinth with the four figures, here too, a fifth one seems missing as one points to an empty area in the middle of the plinth. I had seen images of Upritchard's work, and of some of the other finalists' works, previous to experiencing this exhibition. But I had never seen the work in the flesh. The difference is astounding. Upritchard's work resists photography and reproduction, and this too, in the age of overwhelming communications and surveillance technology, gives me a good feeling, somewhat of an escape route.

Jury

The 2006 jury comprised:

- Christina Barton – writer, curator and art history programme director at Victoria University of Wellington

- Andrew Clifford – then freelance writer, curator and broadcaster

- Wystan Curnow – writer, curator, co-director of Jar Space and English Professor at Auckland University

- Heather Galbraith – then Senior Curator and Manager of Curatorial Programmes at City Gallery, Wellington

Jury's statement

In deciding which artists have had the biggest impact on New Zealand art over the last two years, the 2006 Walters Prize jury left no stone unturned. After extensive deliberations, it was surprising to find that four projects had seemingly found their own way to the top of our list. Interestingly, some of New Zealand's most senior practitioners featured alongside emerging artists, all with fresh, vibrant projects that collectively demonstrated an impressive diversity in New Zealand's current cultural production. Without dispute we had settled on an exceptional group of works and we unanimously agree that this exciting group of projects represent the best produced in New Zealand since the last Walters Prize.

Converting AUT's ST PAUL St gallery into a public spa with dubious restorative intent, Wet Social Sculpture is an irreverently layered result of Stella Brennan'sinterest in the fate of modernism and the idiosyncratic ways that art draws on and is absorbed by popular culture. Neatly combining her ongoing explorations of abstract cinema, psychedelic escapism, suburban consumerism and utopian architecture,Wet Social Sculpture is a witty and engaging critique of how concepts age and are translated into contemporary culture.

It is always pleasing and impressive to see a senior artist's practice continue to increase in energy, range and sophistication and Philip Dadson is currently at the top of his game. Having recently retired from full-time teaching to concentrate on his own work, the last few years have been busy for Dadson and the rewards of this renewed focus have been evident in his work. In particular, a 2003 residency in Antarctica resulted in Polar Projects, a large body of video and sound works, drawings and photographs that have been variously installed around the country. The selectors were especially struck with the video works, which powerfully demonstrate how Dadson uses technology, found materials and the body in his distinctive way to capture and channel the rhythms that resonate in any and every environment, even one as unrelenting as this icy landscape.

Peter Robinson's work has always been a challenge to 'good taste' and is no exception. Here a livid lexicon of sculptural forms pay their dues to artistic heavyweights like Claes Oldenburg, Jackson Pollock, Philip Guston and Franz West, while simultaneously simulating a messy playground of consumerist excess: a veritable feast of cigarette smoke and junk food and their nasty after/side effects. This installation feels like a comeback piece, drawing together Robinson's earliest sculptural pieces with his ongoing examination of the insidious ways in which society is structured: to exclude and prohibit but also to seduce and compel, using the visceral qualities of his materials to get right under our skin.

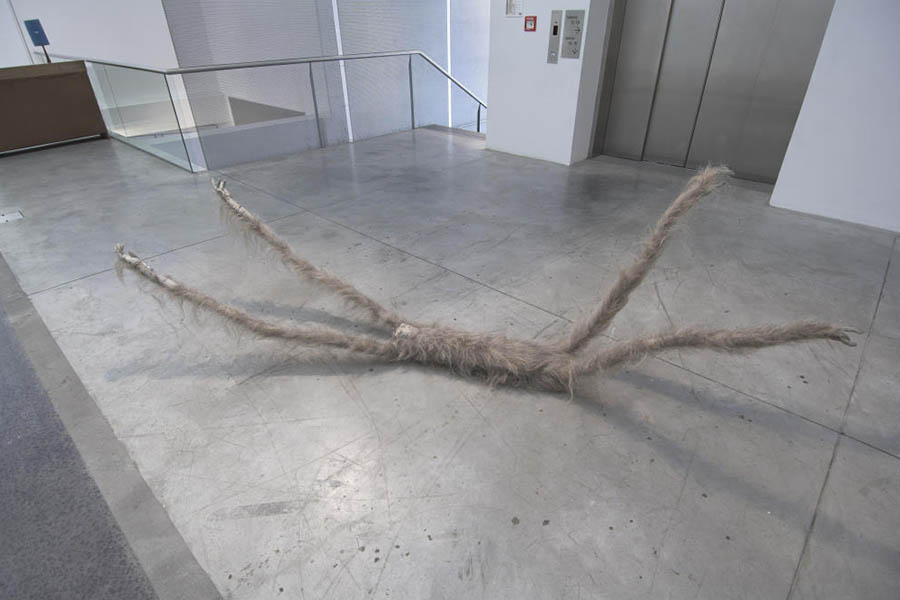

Francis Upritchard is an emerging artist making waves in London (where she lives), New York, and New Zealand, with her twisted view of her particular world and her peculiar take on history. Doomed, Doomed, All Doomed, her 2005 Artspace exhibition, is a case in point. While the title of this mini-survey evokes an apocalyptic gloom perfectly pitched to the tenuousness of our historical moment, its contents speak of the past as she creatively re-imagines it. Upritchard combines desiccated votives and tatty remains with gummy models, half-baked trinkets and museum vitrines, challenging distinctions between sacred and profane, hobbyist and artisan, bric-a-brac and artefact. By compiling this patently fake past with its strangely pathetic cultural inheritance, Upritchard reminds her audiences of what was and is invested in all efforts to hold on to history. She shows how 'our' desires to catalogue and contain are probably driven, too, by a thoroughly primitive fear of annihilation from which none of us are entirely free, not even at this very minute.

Sponsors

Founding benefactors and Principal donors:

Erika and Robin Congreve and Jenny Gibbs

Major donor:

Dayle Mace

Founding sponsor:

Saatchi & Saatchi

Principal sponsor:

Ernst & Young

Major sponsor:

Simpson Grierson

Coordinating curator

The Coordinating curator for the Walters Prize 2006 was Natasha Conland.

Publication

Read the Walters Prize 2006 publication free online via ISSUU

- Date

- —

- Curated by

- Natasha Conland

- Location

- NEW Gallery, lower level

- Cost

- Free entry

Related Content

Related Artworks

Jealous Saboteurs

hockey sticks, plastic, modelling materials

Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, gift of the Patrons of the Auckland Art Gallery, 2006

The Shop

rug, recycled fur, leather, tennis racket, modelling clay

Chartwell Collection, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, 2004

Echo-Logo

single channel video, standard definition (SD), 4:3, colour, stereo sound

Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, gift of the Patrons of the Auckland Art Gallery, 2005

Aerial Farm

single channel video, standard definition (SD), 4:3, colour, stereo sound

Chartwell Collection, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, 2004

Untitled

oil on canvas

Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, gift of the Patrons of the Auckland Art Gallery, 1994

Untitled

wood, ceramic, metal, electrical wiring, glass

Chartwell Collection, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, 2007