This article appears in Art Toi Magazine, November 2020

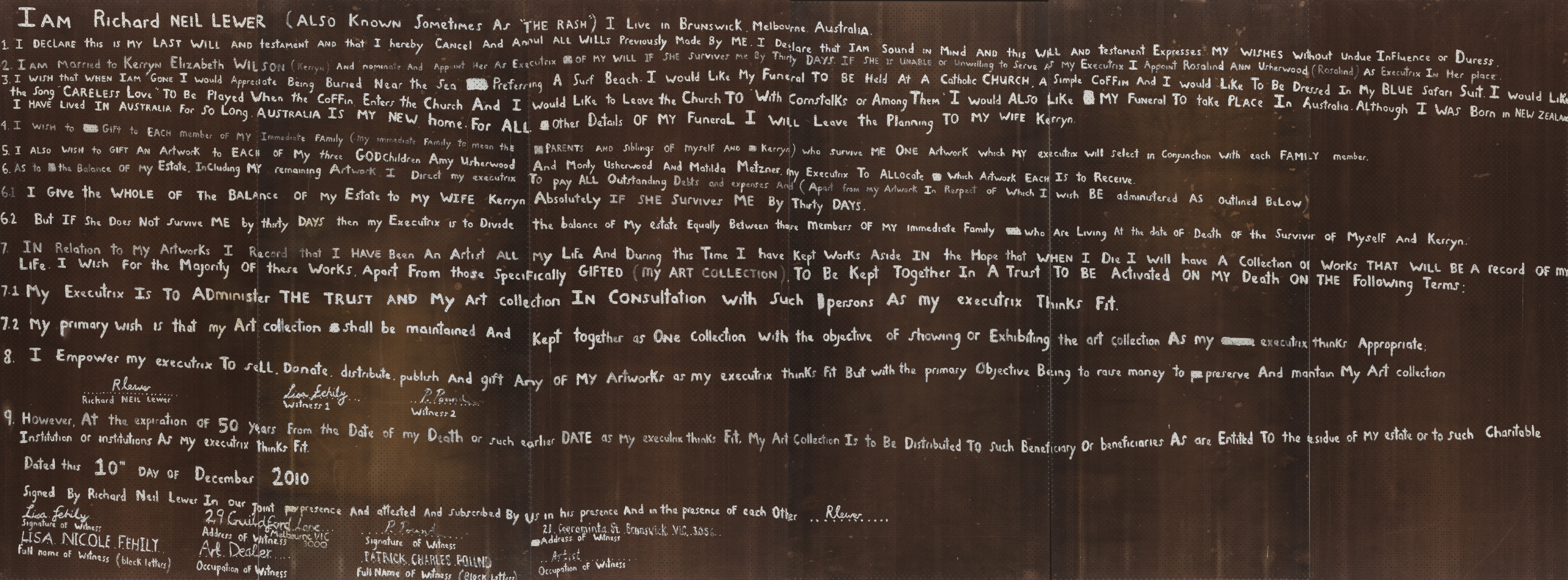

Richard Lewer’s prolific practice has been an exercise in exposure. How much do we show and of what? In a world of coded practices, what glimmer of self do we expose to the world’s prying eyes? Throughout his 30-year career Lewer has dwelt, without judgement, in the dark and often morally complex domain of human nature, dealing with topics spanning sadness, violence, sadism, corruption and embarrassment. In these spaces how do we decide, on a sliding scale of exposure, what is revealed, and what is not? How much is given?

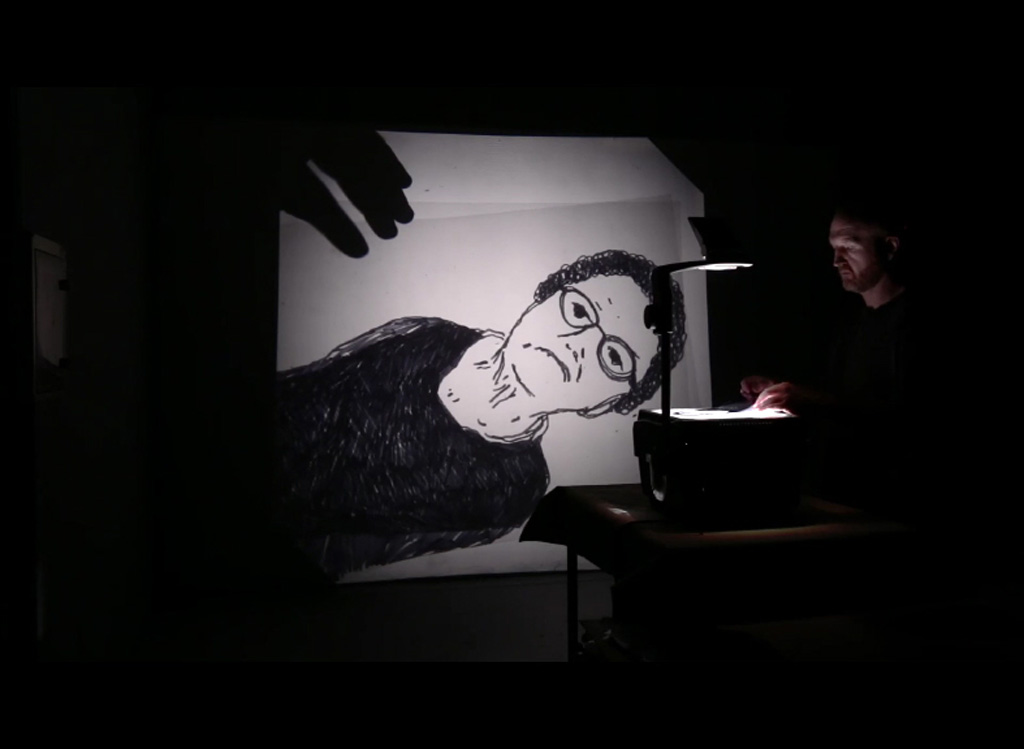

Early in the Melbourne-based New Zealand artist’s practice he began etching into and corroding texture onto brittle metallic painted surfaces. Rendering form painfully, it was as if he was seeking a kind of transmission between his own broken eczema-prone skin and the tormented surfaces of his paintings. Lewer’s work has, then, always revealed an oscillation in focus between his own self and his subject, with varying degrees of self-exposure offered across each series.

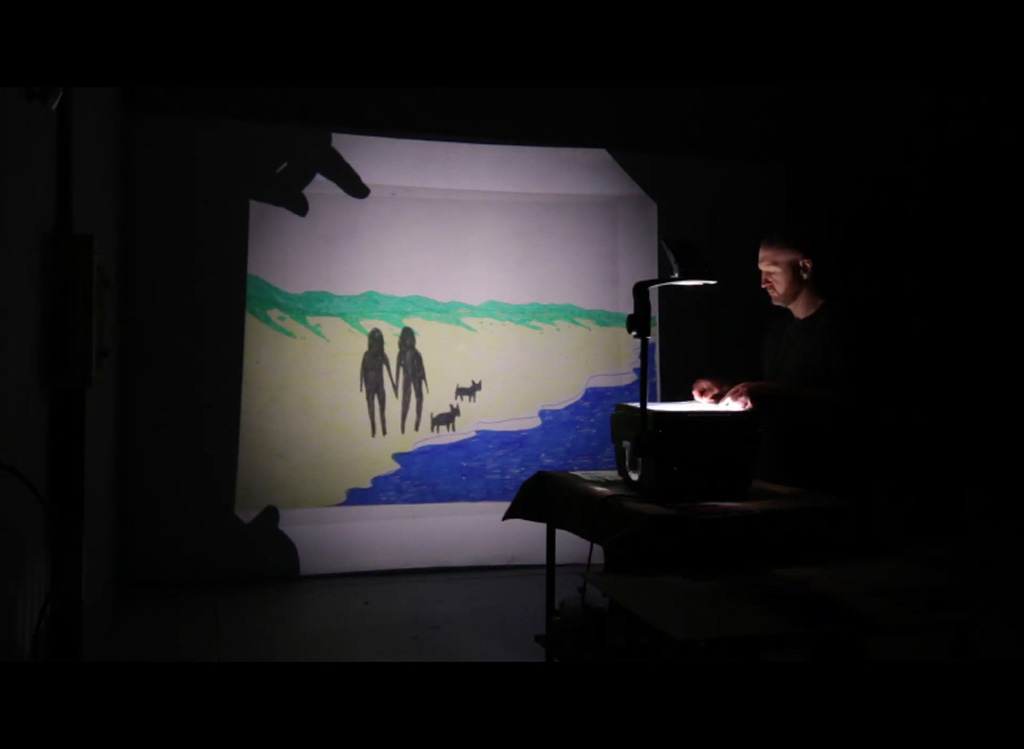

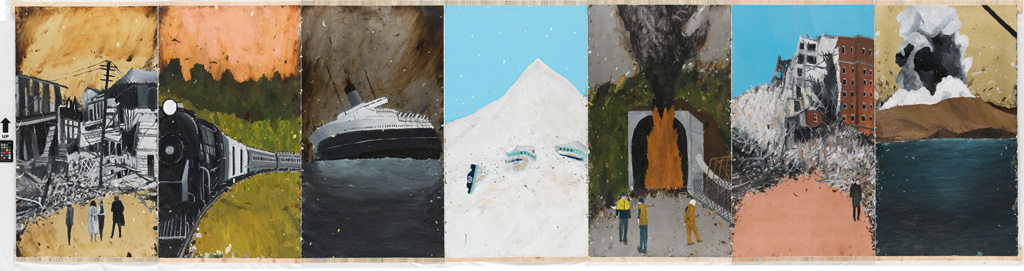

While the early steel works were a direct expression of a fraught inner world, he later turned to the turbulent lives of others, finding in their stories parables for human experience. Over the past 15 years Lewer’s works have seen him become embedded in the personal lives of serial killers, Melbourne’s infamously staunch Federated Ship Painters and Dockers Union, exorcist priests, gangsters, and even the haunting undead. It’s as if he is seeking in this subject matter a darkness that gives shape to form, with his practice becoming a kind of conceptual chiaroscuro rendering of the human condition. We are being drawn into being, our evils, our fears and our embarrassments laid bare.