Thursday 23 May 2013

Matthew Norman

Albrecht Dürer, The Virgin and Child with a Monkey, c1498, engraving, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, purchased 2013

In my previous post I introduced our recent acquisition, a splendid early impression of Albrecht Dürer’s engraving The Virgin and Child with a Monkey, c1498 (state: Meder a). I now want to explore the remarkable provenance (history) of this object.

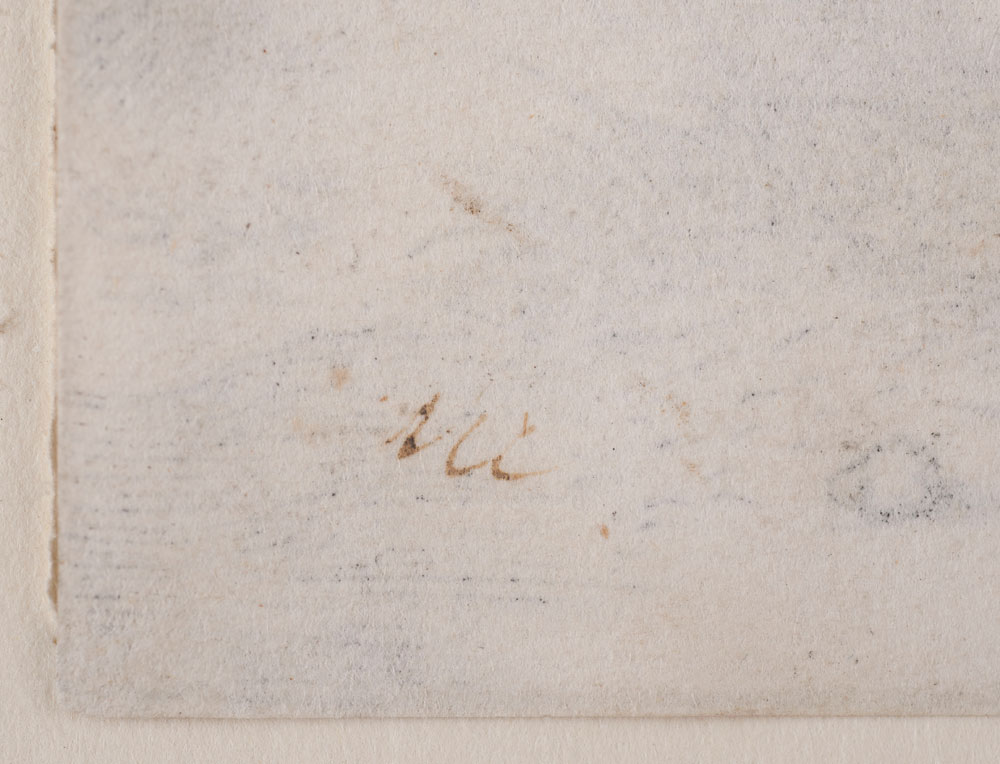

After leaving Dürer’s studio, this impression of The Virgin and Child with a Monkey circulated among collectors and the art market for upwards of 300 years before being acquired by the London-based collector the Reverand Clayton Mordaunt Cracherode (1730-99). Cracherode combined private wealth with a discerning eye and established a collection of several parts, notable among which was a large number of fine prints. Our print carries Cracherode’s mark on the verso (back) at lower left:

Only the finest or most significant of Cracherode’s prints were marked with his initials and the print scholar Antony Griffiths has suggested that he reserved his mark ‘as a sign of special approval or attachment.’ As we know that Cracherode only had a small number of northern prints from the period (compared to his extensive holdings of 16th-century Italian prints, for example), we can be confident that our print was highly prized by the famous collector.

Having served as a Trustee of the British Museum since 1784, Cracherode left his several collections to the Museum on his death. But in 1806 it was discovered that over the course of a year or more, the caricaturist and amateur art dealer Robert Dighton (c1752–1814) had stolen a large number of Cracherode’s prints from the Museum. The scandal was soon picked up by the newspapers and the Trustees struck a deal with Dighton to recover as many as possible of the prints in return for not bringing a prosecution against him.

Recent research by An van Camp (Curator of Dutch and Flemish Drawings and Prints at the British Museum) has revealed the lengths Dighton went to in order to obscure the provenance of his stolen prints. The stamps and inscriptions of previous owners were scratched out and bleached as well as being obscured with false marks invented by Dighton. By obliterating the legitimate provenance of these prints (recognisable through the various marks of previous collectors) and falsifying new histories for his ill-gotten wares, Dighton hoped to sell them without raising suspicion.

Our print shows Dighton’s owner’s mark on the recto (front) at lower right:

This stamp is a tell-tale sign of Dighton’s theft. Combined with the trace of Cracherode’s own mark on the verso we can identify our print as one of those stolen from the British Museum by Dighton and not subsequently recovered. (The British Museum no longer pursues the prints that Dighton stole, and the Gallery has acquired good title to this important work.)

Our print no doubt circulated among private collectors in the years after 1806 before appearing in a commercial exhibition in London at P & D Colnaghi & Co Ltd in 1971, marking the 500th anniversary of Dürer’s birth. A private collector purchased the print from that exhibition for £2000.

In July 2012 our print resurfaced during the filming of the popular television programme Antiques Roadshow during its visit to Stowe School in Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom. While the owner realised that her late father had acquired the print at Colnaghi’s in 1971 she was keen to learn more. London-based dealer Philip Mould examined the print and it became one of the highlights of the day’s visit to Stowe. The print features in episode 13 of series 35 of the Antiques Roadshow (Stowe House) which screened in the United Kingdom in January of this year.

In addition to being an important and beautiful work of art, our print has a most extraordinary story to tell. We hope that Aucklanders will enjoy this delightful addition to their collection.

Further reading:

- An Van Camp, ‘Robert Dighton and his spurious collectors’ marks on Rembrandt prints in the British Museum, London’, in The Burlington Magazine, 155, 2013, pp88–94.

- Antony Griffiths (ed.), Landmarks in Print Collecting: Connoisseurs and Donors at the British Museum since 1753, The British Museum Press, London, the Parnassus Foundation, Ridgewood, NJ, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Texas, 1996, pp43–51.