Wednesday 16 April 2014

Julia Waite

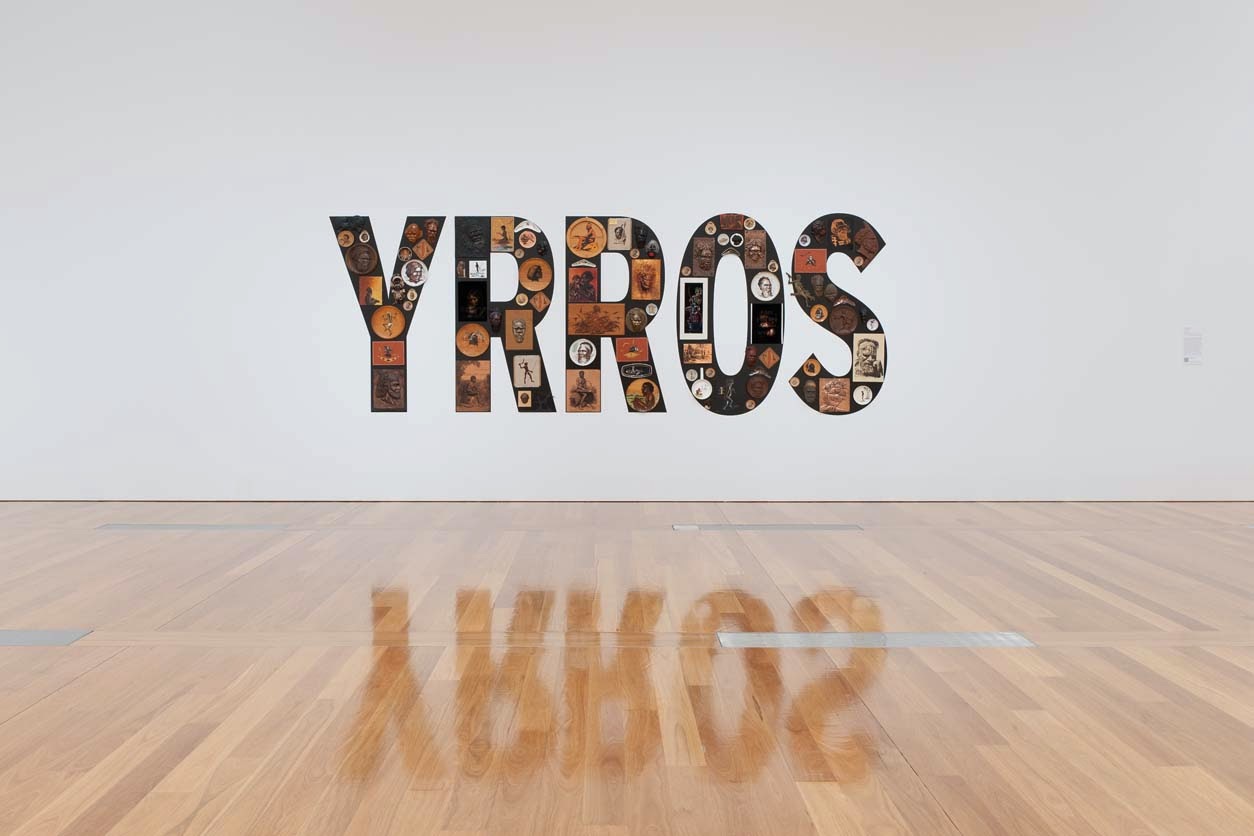

Tony Albert, Sorry 2008, Found kitsch objects applied to vinyl letters,

Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Image courtesy: QAGOMA

My Country includes artworks that directly comment on Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd’s 2008 Apology to members of the Stolen Generations and their families. Tony Albert’s Sorry, 2008, spells out the climax of Rudd’s speech in large black type, but reverses the word to read YRROS and in doing so calls into question the effect of the Apology. For Albert, ‘Sorry is just a word which means nothing if it is not backed up by real outcomes.’ The objects that decorate this text – ashtrays, plates and other pieces of Aboriginalia – were picked up by the artist in second-hand stores. They show a persistent representation of Aboriginal bodies in items of Australian home décor and tourist souvenirs. Male figures dominate – a figure holding boomerang and spear faces off against a kangaroo on a cork beer mat in one of many examples of that ethnographic stereotype, the ‘noble warrior’. Stereotypes such as this, authored by someone else, erase individuality. They do not reflect the realities for the Stolen Generations, or those before them. Covering arguably the most important word of Rudd’s Apology in the material which helped build a generalised and damaging perception of Aboriginal people offers uncomfortable visual evidence of why the Apology was necessary.

A group of works in the exhibition bring the realities of those generations and families affected by racist laws and practices to light, bridging the gap between collective and individual histories and emphasising the personal with artworks which embody specific familial stories and practices. Some of these works relate to the body, recalling objects that were worn or carried, and convey a sense of everyday realities – their physicality evokes the spirit of the individual and their daily struggles.

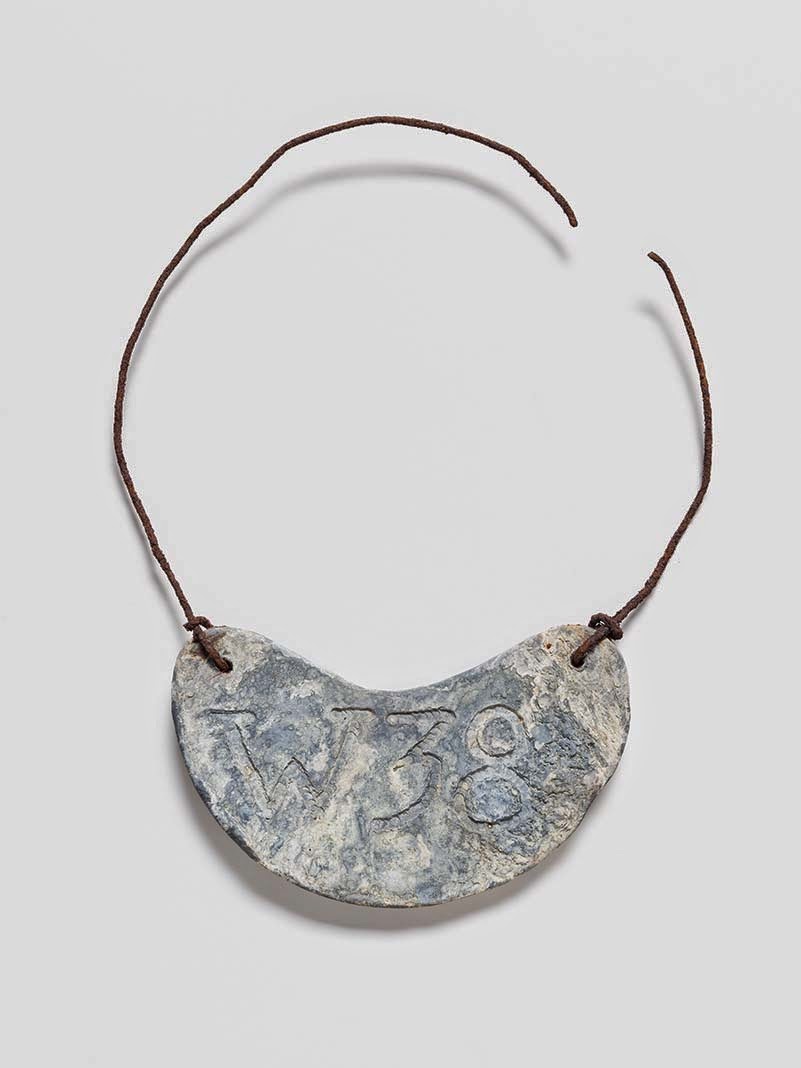

Dale Harding, Unnamed 2009, lead and steel wire

Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Image courtesy: QAGOMA

Dale Harding’s Unnamed, 2012, a lead breast plate inscribed with his grandmother’s new name – ‘W38’ – connotes the harsh treatments and the specific use of ‘king plates’ as a method of identification. The rust and weight of the object with its alphanumeric code symbolises the dehumanising process of classification and control; its decayed surface suggests a forgotten or buried history. Looking at the breastplate gives us a sense of connection with Harding’s grandmother, and we empathise with the indignity she would have felt being forced to hang the large, heavy plate around her neck and having her name replaced by a code.

Wilma Walker, Kakan (Baskets) 2002 (installation view)

Individual stories are powerfully communicated in works which convey a sense of the physical presence of the body. Wilma Walker’s Kakan (Baskets), 2002 recalls the baskets made by her mother. As a baby, Walker was hidden in baskets like these to avoid being forcibly removed from her family – to avoid becoming one of the Stolen Generations. Looking at the baskets’ bulbous forms we can easily imagine her tiny body curled up inside and covered by leaves.

Foreground Wilma Walker, Kakan (Baskets) 2002,

background Tony Albert, Sorry 2008 (installation view)

One of the most striking moments in the exhibition is the presentation of these baskets in front of Tony Albert’s Sorry. Here, the life of someone personally affected by a state policy in practise confronts Rudd’s Apology, as interpreted by Albert. Walker’s handmade baskets, infused with the memories of her early life and with the making traditions of her people, evoke a sense of intimacy and human frailty and contrast the brittleness of the mass-produced Aboriginalia in Sorry. Both works remind us of trauma suffered and together create a confronting reminder about the need to honestly face historical facts.

Bindi Cole, I forgive you 2012, Emu feathers on MDF board

Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Image courtesy: QAGOMA

In the exhibition’s final room Bindi Cole’s response to the 2008 Apology is writ large in emu feathers attached to letters. The sensual and protective qualities of I forgive you, 2012 – its layers of soft plumage – look capable of absorbing shock, which in forgiving one must do. Like Wilma Walker’s baskets, I forgive you was made by hand, each feather stuck down individually to create each word of the powerful sentence. In contrast to the critical position of Albert’s Sorry, and its seeming rejection of the Apology, Cole’s feathered forgiveness is empowering – reconciling differences and opening the door for future relations. According to Cole, ‘forgiveness is about taking your power back . . . no longer allowing that thing that hurt to live inside you.’

Image credits:

Tony Albert

Girramay people

QLD b.1981

Sorry 2008

Found kitsch objects applied to vinyl letters

99 objects: 200 x 510 x 10cm (installed)

The James C Sourris, AM, Collection

Purchased 2008 with funds from James C Sourris through the Queensland Art Gallery Foundation

Dale Harding

Bidjara and Ghungalu peoples

QLD b.1982

Unnamed 2009

Lead and steel wire

35 x 26 x 3cm

Gift of Julie Ewington through the Queensland Art Gallery Foundation 2013

Wilma Walker

Kuku Yalanji people

QLD b.1929 d.2008

Kakan (Baskets) 2002

Twined black palm (Normanbya normanbyi) fibre (basket), with lawyer cane (Calamus sp.) fibre (handle)

Three baskets: 93 x 37 x 36cm; 77 x 29 x 26cm; 68 x 32 x 31cm

Commissioned 2002 with funds from the Queensland Art Gallery Foundation Grant

Bindi Cole

Wathaurung people

VIC b.1975

I forgive you 2012

Emu feathers on MDF board 11 pieces: 100 x 800cm (installed, approx.)

Purchased 2012. Queensland Art Gallery Foundation