This idea was tested in late April at the Auckland Philharmonia Orchestra’s concert, Gallery of Sound, which occurred in collaboration with Auckland Art Gallery. It featured Ravel’s orchestration of Mussorgky’s Pictures at an Exhibition and five new works by New Zealand composers Chris Adams, Sarah Ballard, Linda Dallimore, Glen Downie, Reuben Jelleyman, inspired, respectively, by artworks on display at Auckland Art Gallery – Petrus Van Der Velden’s Otira Gorge, 1912, James Chapman Taylor’s The Wing in a Frolic, circa 1945, Gretchen Albrecht’s Aotearoa – Cloud, 2002, Jean Horsley’s Hot Coals, 1988, and Gretchen Albrecht’s Golden Cloud, 1973. The composers took the form of the art into consideration when transcribing what they experienced or saw into music: mixed visual elements transformed into dark-sounding and innovative percussive instruments, motion and dualism transformed into a mixture of orchestral control and improvised intuitive solo singing, up and down brushstrokes transformed into glissandos, rhythmic brushstrokes transformed into erratic rhythms, and washed and filtered colours transformed into cyclic musical phrases and overlaying textures. The dialogue transported the audience into the artwork themselves where they could ‘hear’ every brushstroke. Gardiner would call this the ‘shared structures in sentient, aesthetic, data management’, meaning that where music composes ‘data’ in time, the visual arts compose ‘data’ in space. Both complement each other in their operation.

The 2017 Chartwell Show Shout Whisper Wail! at Auckland Art Gallery (20 May – 15 October 2017) addresses the relationships between voice or sound, image, space and time. Curated by Natasha Conland, the exhibitions calls on its audience or viewers to respond to the artists’ initiation of communication. Whether or not an artist is successful in holding our attention is determined by our willingness to open up, engage with their art or express ourselves in the environment they create.

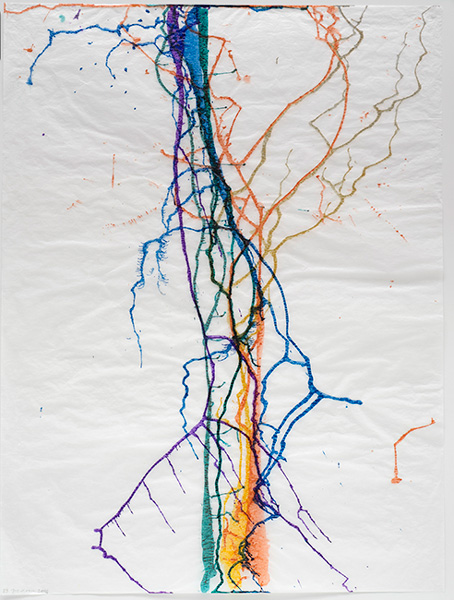

In the first exhibition room of Shout Whisper Wail!, a collaboration between art collective et al. and composer Samuel Holloway fills a square gallery space. Pasted onto the walls are Holloway’s music scores, which resemble the dynamic interactions between composer and artist. In the centre of the room, among other sculptural elements, stands the 2013 et al. work, Upright Piano. Conland explained that ‘et al.’s long history of work with sound and voice within installation practice makes their work particularly relevant’ in this exhibition. Pages from the annotated score perch on the music stand, ready to be played. Concentric circles are taped onto the floor around the piano, as if they were stage markings, and a single light hangs above the piano adding intimacy to an otherwise ‘working’ environment. Nearby a bucket with a speaker on top every so often spurts out chaotic piano melodies, as if there is a pianist hidden nearby working on a composition. This working environment is disrupted further by a scattering of stools that wait for the musician’s audience to take their seats for a concert. People are invited to sit down at the piano and play the score, which has been overlaid with additional mark-making that disrupts the reading of specific notes on the fine musical ledger lines. The interpretation of these marks is left to the piano player, and in this way Holloway and et al. initiate an open dialogue between artist, composer and performers.

Confusion inevitably occurs when audiences are invited to interact with an object. This is not restricted to art galleries – interactive museum exhibits face a similar problem. When society has conditioned us for years to ‘look and don’t touch’, the onus turns to the artist to find a way to break down this conditioned barrier if they want us to engage physically with their art. Conland explained that Holloway ‘led the response here as from his point of view, caretaking the score, he was keen to ensure that members of the public didn’t use the piano without making an “attempt” to read the score, including the marks.’ Positioning gallery assistants in the room helps bridge what could be a blurred understanding of interaction. Gallery Assistant Madeleine Morton echoed Conland and Holloway’s specifications regarding interaction with the exhibit:

‘At first it was decided people could sit and play whatever they wanted, because no one would likely be game enough to play the marked score. Then they added the condition that we could ask people not to play if they were playing Chopsticks. Then Chopsticks was considered a real enough danger for the final call to be no playing encouraged at all, barring people wandering through and playing a few notes.’

Making such a call on audience interaction with an artwork highlights the difficulties artists and curators currently face. But restricting an audience from playing an artwork that was purposively created for interaction seems unusual. Of the times she’s been in the space, Morton says no one’s attempted to play more than a few notes. ‘Maybe because the chair in front of the piano has no seat. People sheepishly play a key or two, look bemused at the score and move on.’

But what happens when people do choose to interact with it? ‘The most visceral reaction comes when people round the corner having heard a few notes, expecting to see someone at the piano and no one is close enough to have played,’ explained Morton. ‘That quirk of the exhibition’s soundscape caught out a fair few [Gallery Assistants] as well. And every other security guard.’ Over time, she’s found that she’s been more enthusiastic about encouraging the audience to participate and letting them know they can ask her questions about it. Nonetheless, she admits ‘most seem disconcerted by any overt enthusiasm in the contemporary art space.’ Conland highlighted the positive response this work has had in the exhibition: ‘In particular, it is well known that audiences for contemporary art enjoy immersive experiences which engage multiple senses.’

Upright Piano will be ‘activated’ with four scheduled performances over the course of the exhibition. ‘It was always the artists’ intentions,’ Conland explained, ‘that the work would have “redactions” or performances of a highly varied nature from professional pianists and/or improvisational [pianists] taking into account both the score itself, the visual markings and the form of the altered piano itself.’