Reprinted from Art Toi Magazine, November 2021

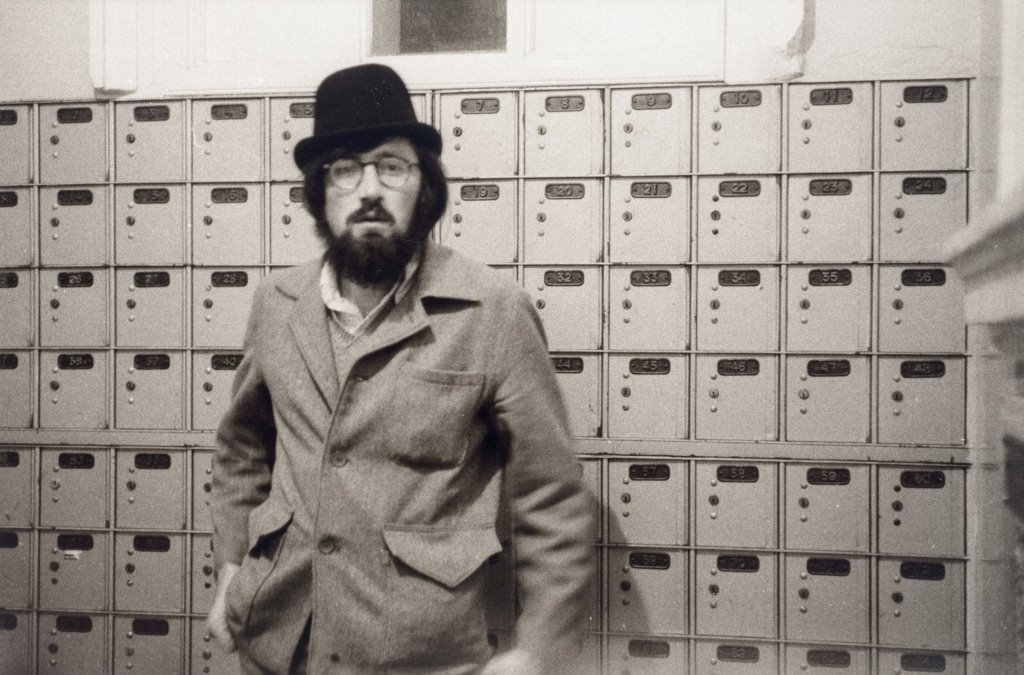

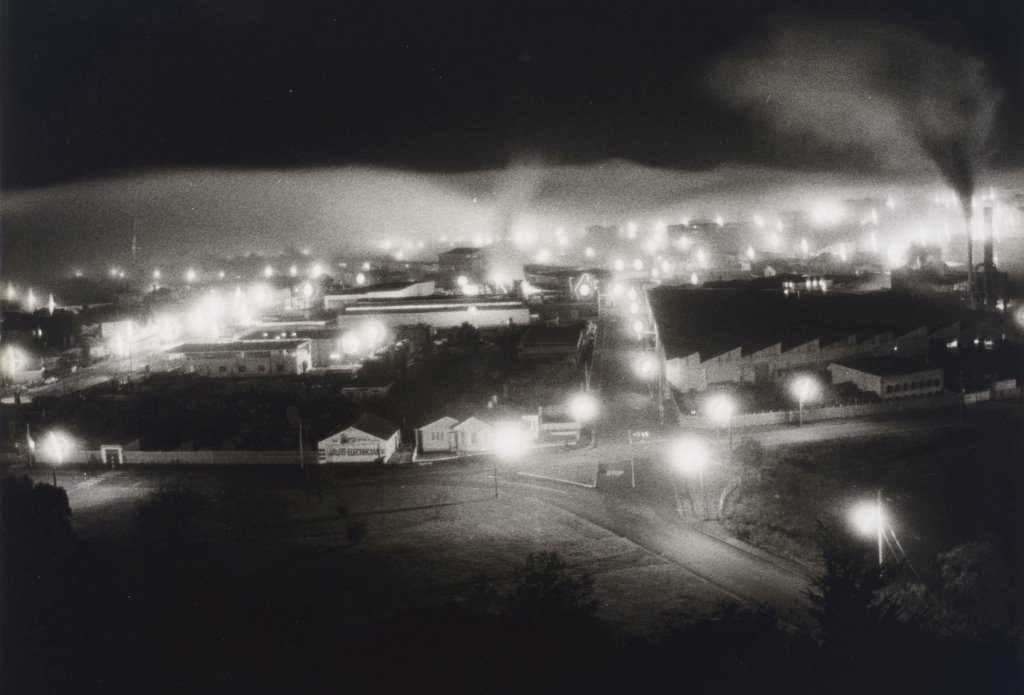

Ron Brownson: In 1975 I was living right next to Snaps, Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland’s first photographic gallery. Established by Glenn Busch and Alan Leatherby, Snaps’s inaugural exhibition profiled Swiss-born Max Oettli’s photographs. I worked as a gallery volunteer, which meant I could look closely at and spend extended time with Oettli’s black and white images. They proved an eye-opener to me: Oettli was committed to capturing inner-city street life with grit and humour while using the opposing light perspectives of night and day.

A number of the rare vintage photographs presented at the 1975 Snaps show are included in this selection, which the artist and I have written short comments on. These join more than 50 other photographs in the Gallery’s exhibition, Max Oettli: Visible Evidence – a strong representation of his practice during the 10-year period which also includes work from the 2018 gift Oettli made to the Gallery of his Auckland photographs.

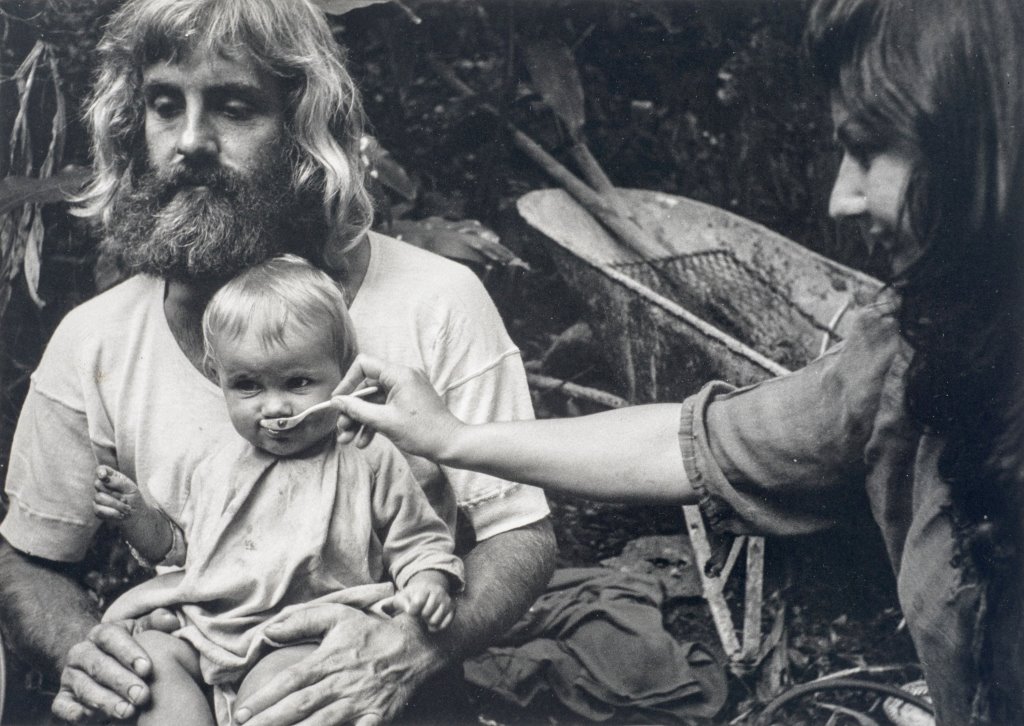

The decade Oettli was active in Auckland coincided with the time when photography began to enter our art scene. The use of miniature 35mm cameras was widespread, providing photographers with technical versatility to match the varieties of imported film and stocks of photographic paper that were becoming available. Even in 1975, photography exhibitions were infrequently encountered in local galleries, but this did not discourage Oettli. An innovative artist, his vocation was independent of the marketplace – he chose when, what and where he photographed, working outside commercial constraints. Being spontaneous and intuitive, he approached his subject matter like a visual diarist, adroitly using a candid ‘shoot-from-the-hip’ technique influenced by French humanist photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson.

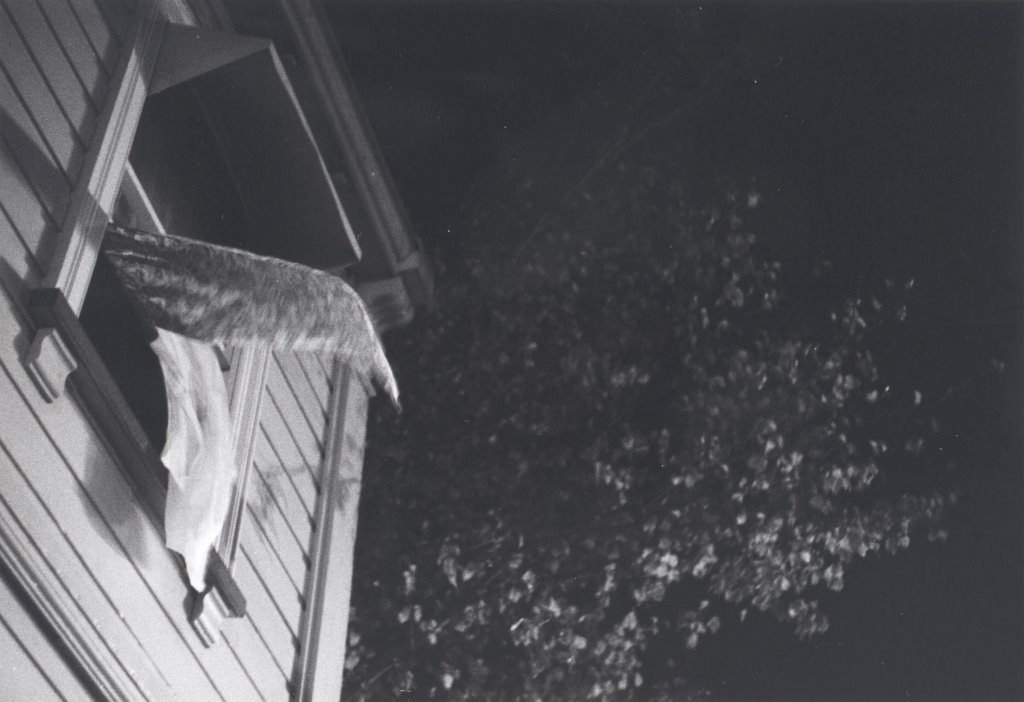

Unlike local camera club artists, Oettli avoided the tradition of ‘fine art’ exhibition prints, relishing instead the contrast of dark versus light. His images vary spatial depth, experiment with light and do not favour balanced exposures or pre-determined compositions. This imaginative confidence gives his photographs emotional vitality and expressive momentum.

Immediacy, rapid response and quirkiness are central to Oettli’s photographic practice. His images oppose notions of following a preconceived or correct photographic mode, and by concentrating on graphic intensity rather than conventional pictorial finesse, Oettli has helped redefine the relevance of street photography. Using his camera not merely as a functional extension of his curious eye, but instead an apparatus reflecting a discerning mindfulness, Oettli captures reality in a spontaneous, unrehearsed and intuitive way.

As a fellow immigrant from continental Europe, Oettli’s photographs share affinities with the work of Marti Friedlander and Ans Westra. Like them, he observes this country from a forward-looking urban perspective with a photographic agenda to seek out how people in New Zealand live. Oettli was also close to other New Zealand camera artists, including John Fields, John B Turner, Tom Hutchins and Laurence Shustak, who worked as professional photographers while maintaining their own personal artistic vocation.

Over the course of a decade Oettli emerged as one of New Zealand’s ground-breaking photographers. Dedicating himself to independent picture making – and avoiding editorial direction – the distinctive images he has created offer a live, subjective view of a time of immense change when New Zealand was opening up to the world and engaging in the cultural, political and social exchanges that would set the course on which we now find ourselves.