Reprinted from Art Toi Magazine, November 2020

Twenty-twenty was a year of cacophonous crises which ruptured the patterns and structures of our lives. Yet in the middle of that upheaval – perhaps as a response – there was a quiet turning inwards here in Aotearoa New Zealand, a narrowing down of focus to the here and now, to the confines of our proximate parameters. Isolated from the rest of the world by travel restrictions, we became a ‘bubble’ defined by our border.

Some commentators said New Zealand had become excessively isolationist; others saw us as an attractive utopian refuge offering the hope of some semblance of calm and normalcy at a time of global uncertainty. President Trump’s bizarre criticism of New Zealand’s Covid-19 approach brought these two attitudes into collision: idyllic photographs of the New Zealand landscape shared across social media with the satirically mocking hashtag #NZHELLHOLE.

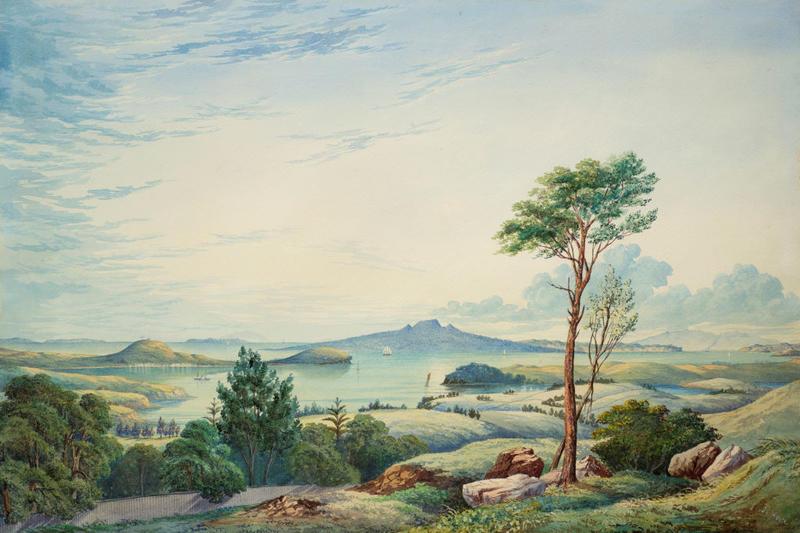

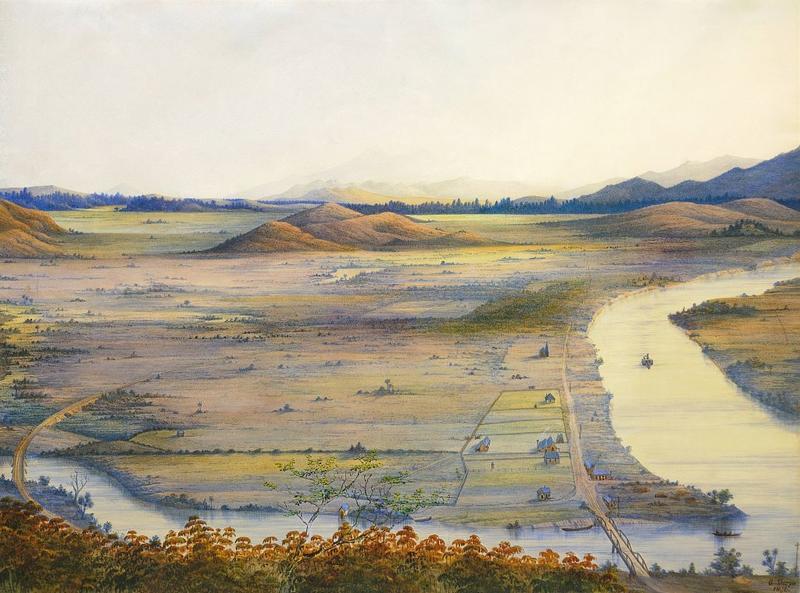

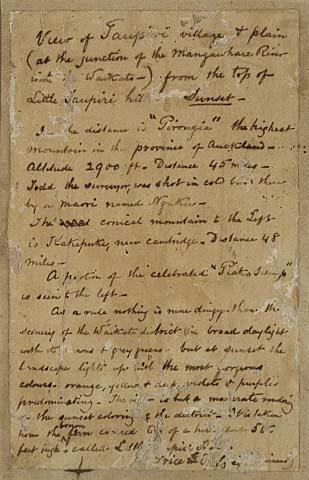

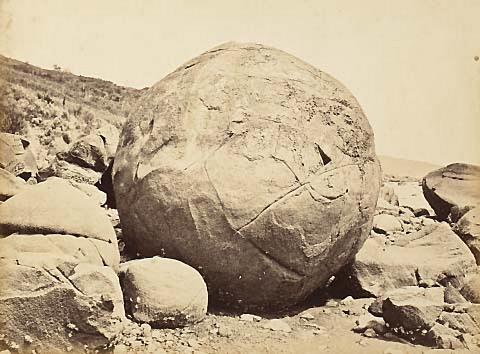

This pandemic, and its related presidential rebarbative rebranding, made me think about the early colonial perceptions and depictions of the New Zealand landscape. How did these depictions reflect and shape our national identity? What were the reasons for this? How do we work as active participants in interpreting, perpetuating and enacting these narratives?