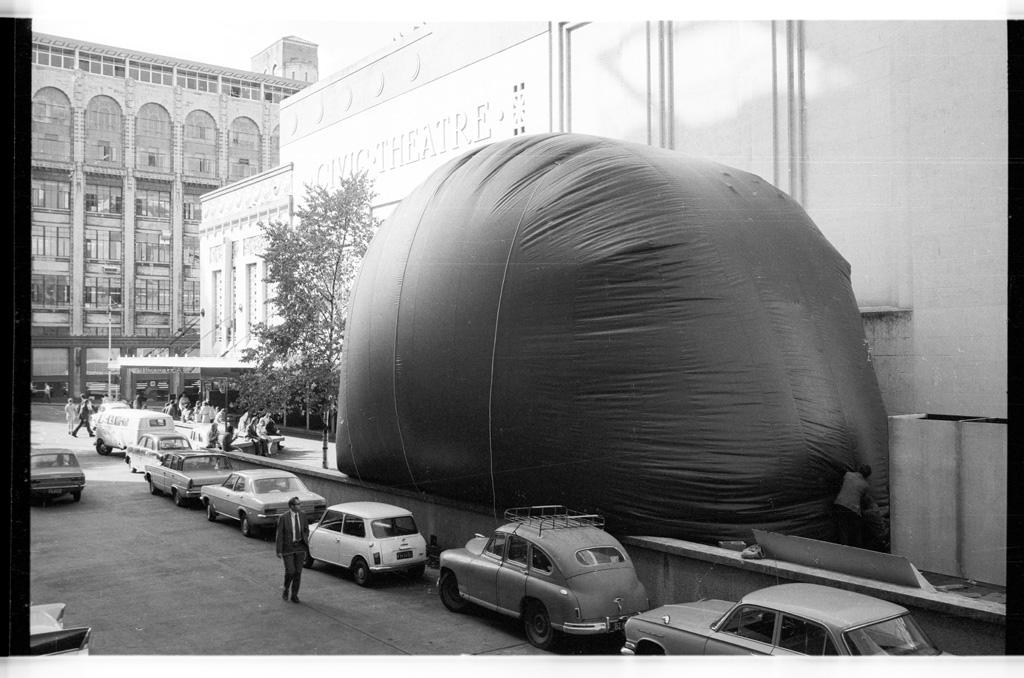

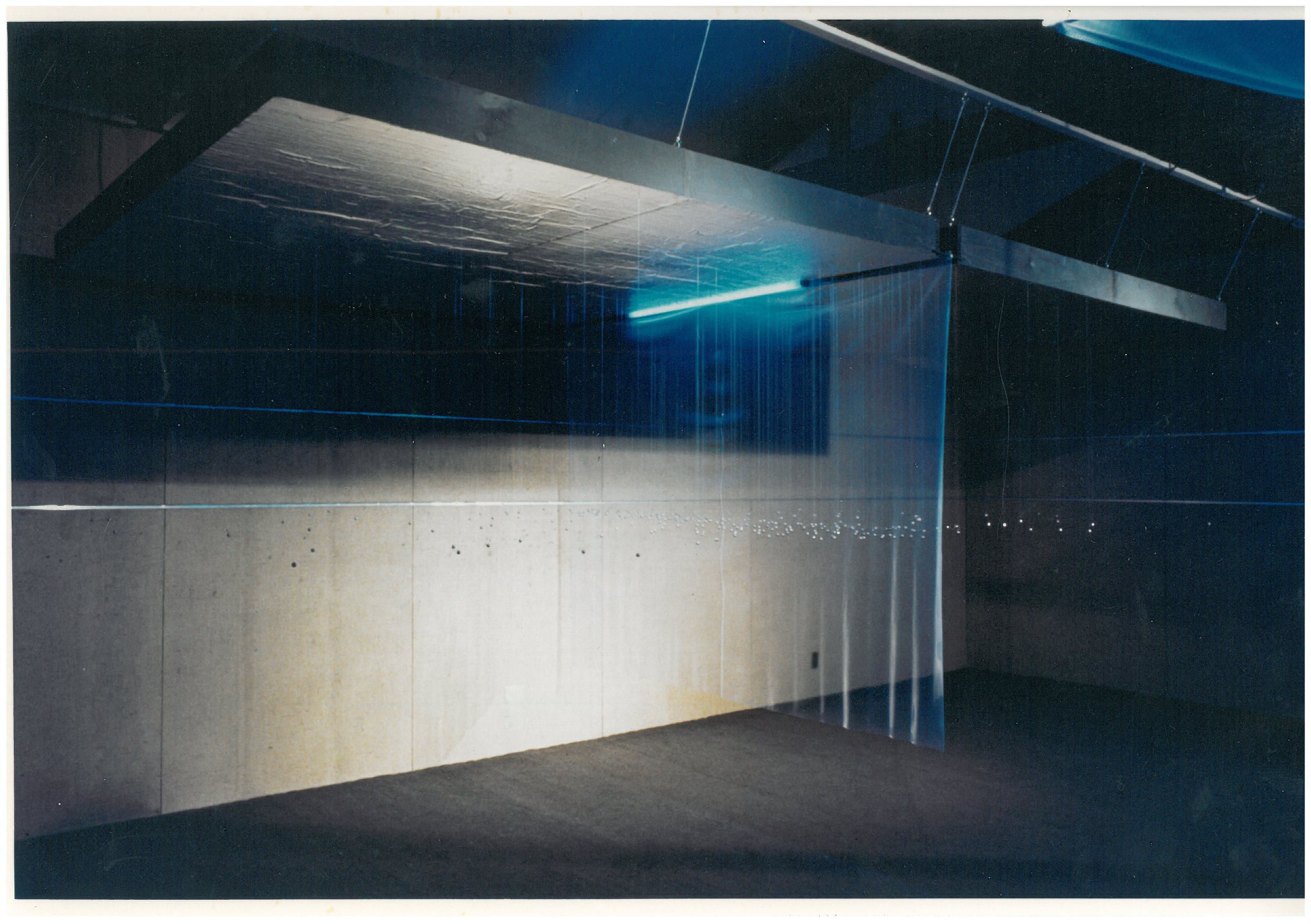

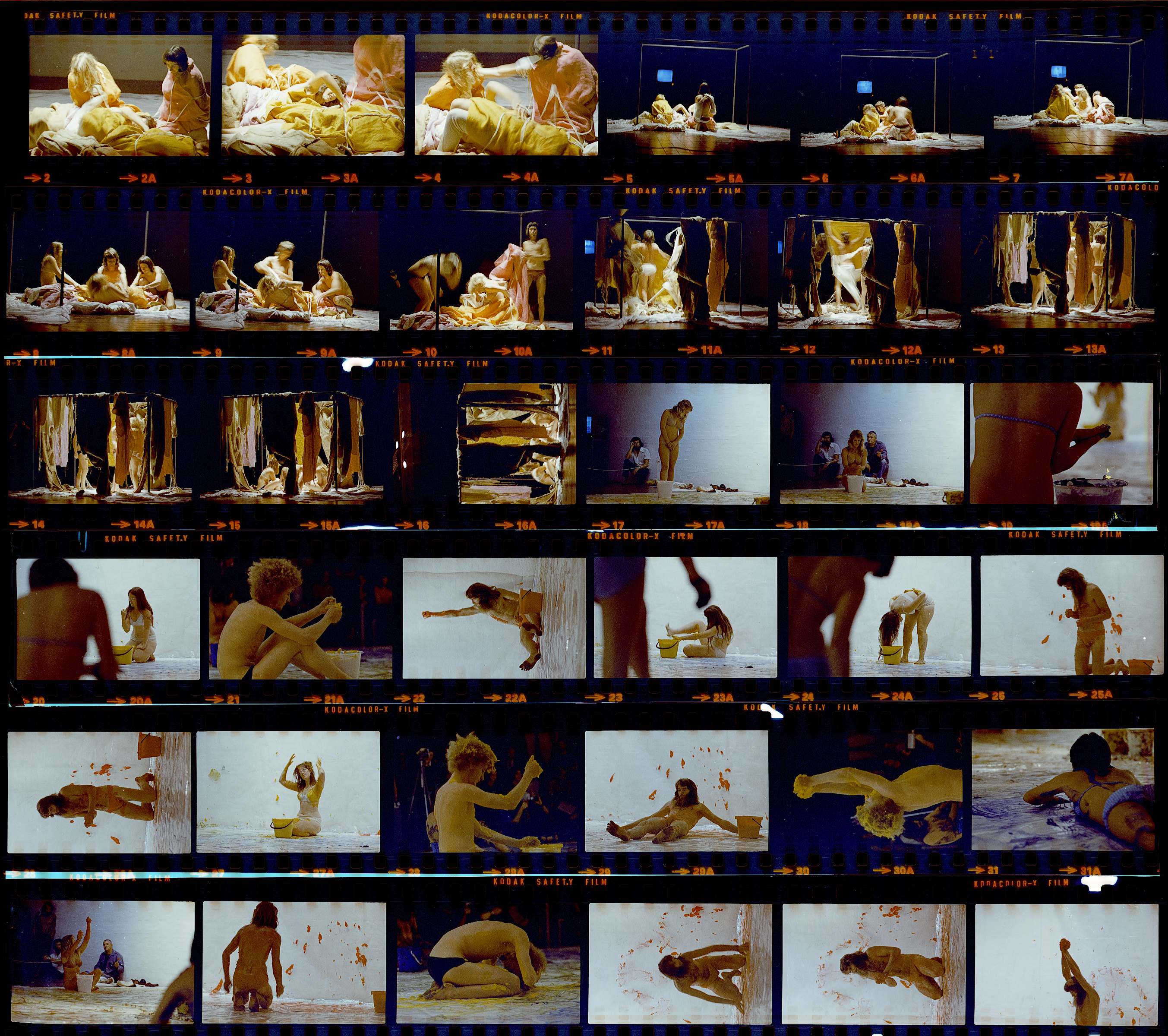

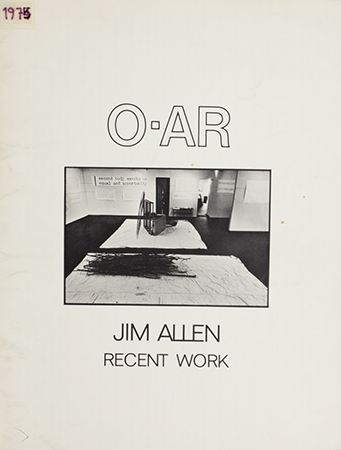

In the opening years of the 1970s, a very different kind of art became visible in Auckland City and its surrounds. These changes were emerging from students of sculpture, under the leadership of artist and teacher Jim Allen. From the moment of his 1960 arrival at Elam School of Fine Arts until his departure to Sydney in 1976, Jim Allen was a new kind of teacher of a new kind of sculpture. His presence was felt in the city as an artist, an educator and an organiser of a striking range of art and activities. In particular, during the period of 1969–76 Allen pushed the activity and thinking of this new generation of artists outside the art school and into urban and natural surrounds. Allen’s leadership drove experimentation and opportunities for large-scale encounters with art. Traditional sculptural form evolved into demonstrations of Conceptual art, performance, events, video and new technologies. Perhaps for the first time these advances were occurring on a par with global revolutions in art. In the work of this era, we see work with an intense engagement with the body, the concept of ‘earth’ before the internet age, and an often comic response to life of the time.

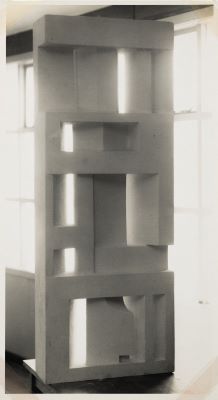

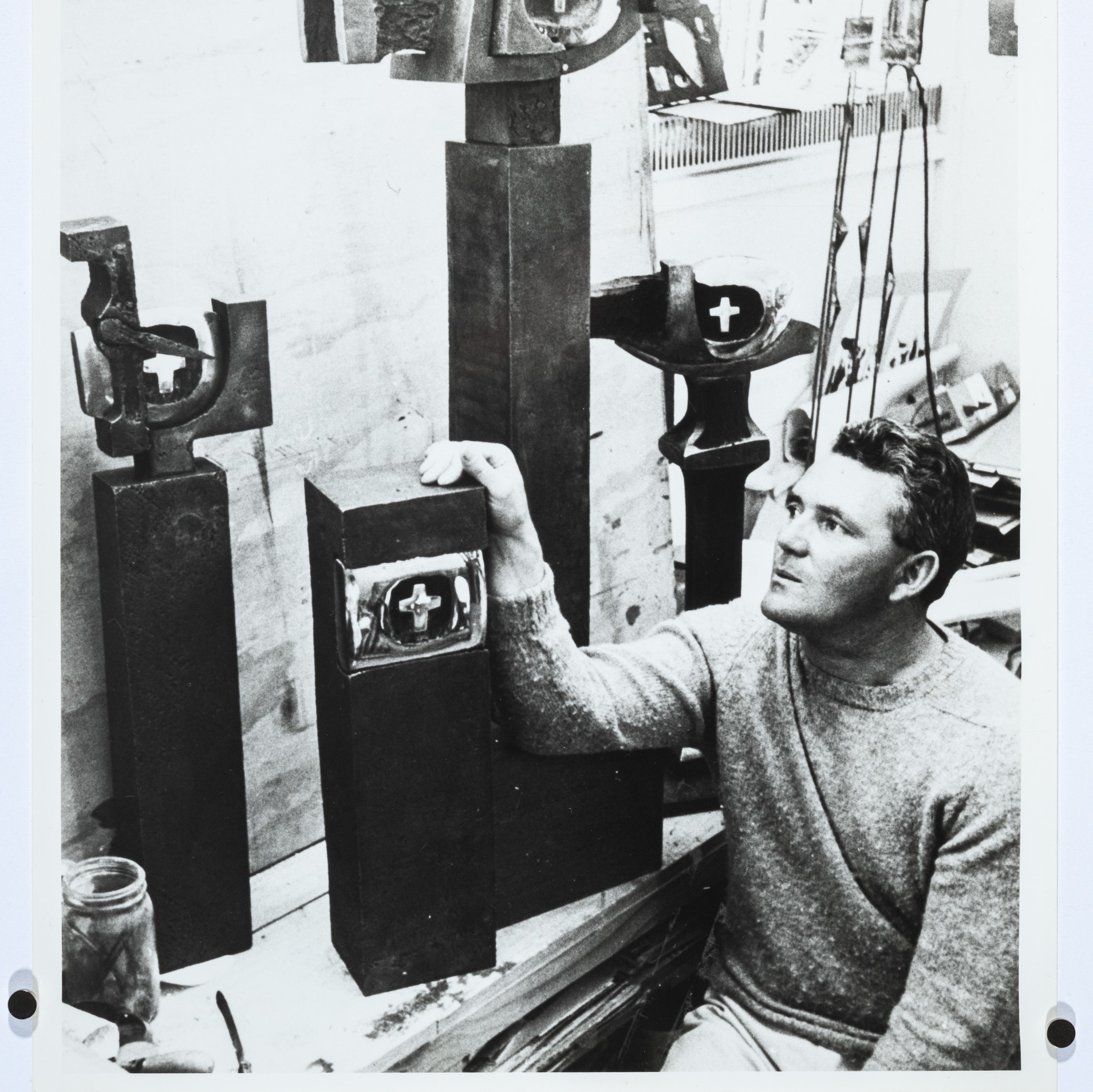

The depth of thought underpinning Allen’s own works is still largely unknown, despite valiant attempts to research and regain what was largely a decade of ephemeral practice. This month Jim Allen turns 100, and what better moment to reflect on the achievements of his lifetime. In 1969 Allen was already 47 years old when he returned to Elam after a long year of sabbatical travelling to the United Kingdom, Europe, United States of America and Mexico, a trip which was a catalyst for reflection on global changes happening in art practice and education. By 1969 he had an established and notable career as a sculptor, with several public works across New Zealand – Light Modulator, 1959 at Auckland City Art Gallery as well as commissions in the Bay of Plenty (Wairaka, 1961) and at John Scott’s Futuna Chapel in Wellington, 1962.

Nonetheless ever the pragmatist, Allen knew by 1969 that things had to change substantively and radically if art was to connect with life. He had prior experience of this kind of self-reflexivity. After serving as a machine gunner in the war (1942–46) Allen resolved to train as an artist, eventually heading to the Royal College, London. Upon his return to New Zealand in 1952 he was guided by Gordon Tovey to work as a teacher in the Far North, where he spent much of the 1950s, influenced by educator Elwyn Richardson. An untrained teacher, Allen has said that, ‘It was only after my time at the Royal College, London, and visiting major art galleries and museums in Europe, that I came to realise that “teaching” could lead to gross inhibition and distort natural aptitudes’. Instead, he channeled imaginative play and free energy into the classroom, with much hands-on making. He remarked that ‘people have said I didn’t seem to teach anything, and this always pleases me. My effort went into creating a supportive environment, encouraging experiment and exploration, insisting that people find their own answer rather than providing them with one. I guess it was backdoor teaching, not leading from the front.’ However this modesty belies his activity behind the scenes working to enable visibility for artists even at their earliest stage, including, in 1954, bringing a truckload of sandstone and pumice sculptures by students from Kaitaia College down to Auckland City Art Gallery for exhibition during the directorate of Eric Westbrook.