Looking to the past can feel nostalgic, allowing us to revisit a simpler time in our lives. But it can also offer creative possibilities that bring a critical awareness to the present, and this is clear in the practice of John Pule. Born in 1962 in the village of Liku in Niue, Pule immigrated to New Zealand at the age of two and is now a leading artist, poet and novelist. Since 2017, Pule has been based in Niue, a locality that presents exciting opportunities to re-create stories and memories that are strengthened by connections with family in Liku.

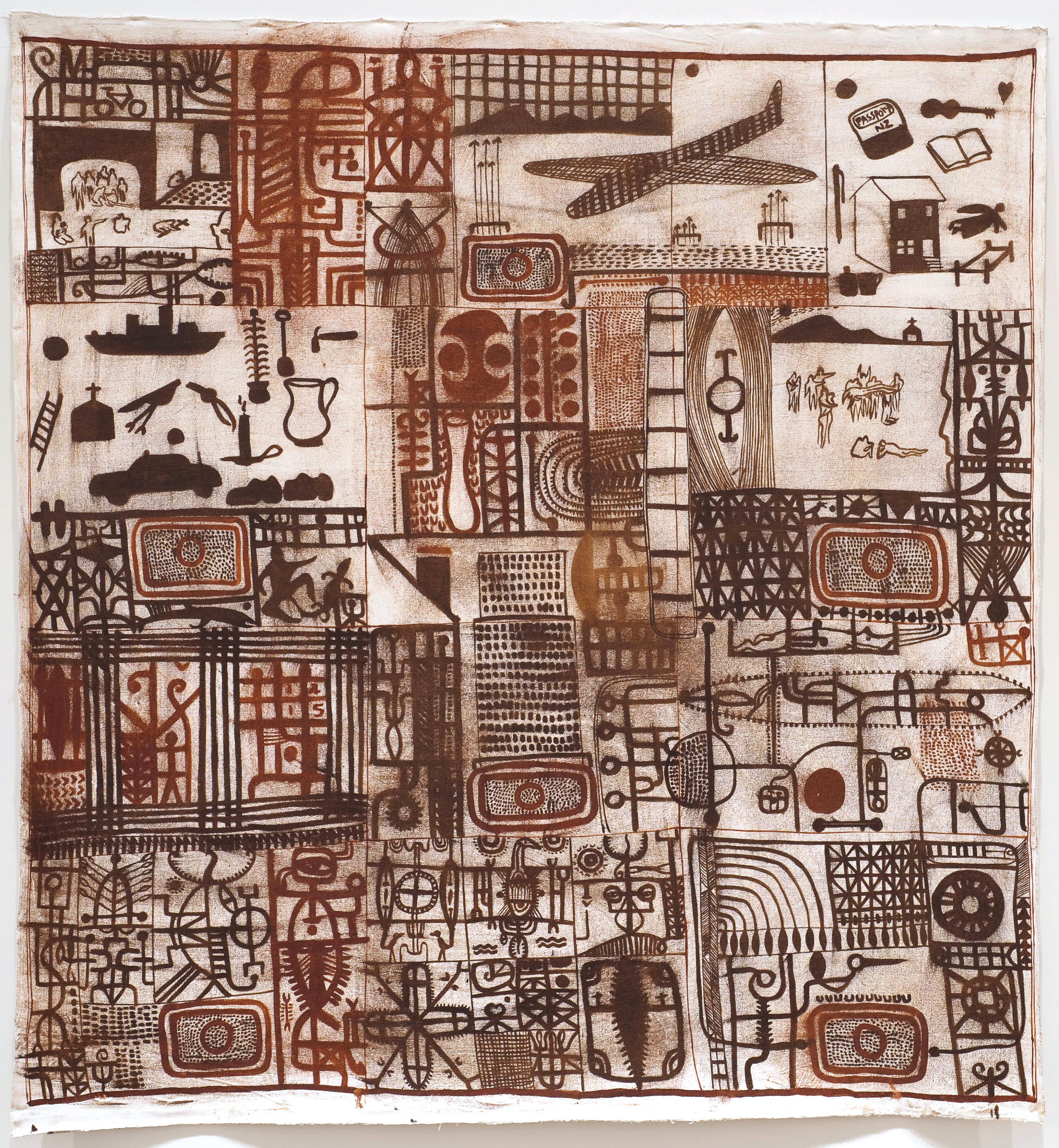

The Gallery has important examples of Pule’s earlier works from the 1990s, which are energised by his focus on hiapo (decorated Niuean tapa cloth) of 19th century through which he developed a unique pictorial language. Hiapo is characterised by a grid structure within a rectangular or circular format in which forms are meticulously handpainted. Motifs include abstract shapes, plant forms, men and women in Western dress, stars, fish or texts of personal names or places. All of these are painted in dark colours – often brown, burnt umber and black. Pule likened the structure of hiapo to architecture: [1]

‘When you look down on to the tapa, the patterns look like a plan of a village, or a plan of tracks going down to the ocean. . . I stretched the canvas, bought some paint – burnt umber, like the colours used on tapa – then I became an architect. I started remembering the roads and pathways and houses in the village I come from, and other rooms of our house, and I put all that down, and did images, birds, a lot of personal symbols, and now and then a triangle.’

His architecture combined aspects of hiapo with personal iconography in ways that politicised tapa. Thematically, his works reflected a type of fragility of life, relationships and kinships – further evoked by the poetic nature of the titles he gave his works which reference departures, returns and arrivals.

This is evidenced in Take these with you when you leave, 1998, where Pule mimicks the materiality of hiapo by painting onto a loose unstretched canvas. The composition is arranged in a rough grid structure and densely filled with symbols that are politically and emotionally charged. On the upper-left corner is a silhouette of the Maui Pomare, the ship that ferried Pacific Islanders, including Pule’s family, to New Zealand in the 1940s and 50s. There is also a two-storey state house where the artist grew up in Ōtara; a pen to write letters and stories with and his New Zealand passport, the stamp of his new National identity.[2] Connections to the homeland are represented in the young plant with its roots wrapped in a bundle of soil and reference Pule’s father’s vegetable garden that was replete with cabbages and other crops brought over from Niue. In the top-right-hand corner of the work is Pule’s father’s guitar with which the artist recalls ‘the old man sang sad songs of Niue’.[3] Below them is a jug the artist used to carry water back and forth to his dying uncle while tending the old man as a boy.[4]

This small sampling is part of a unique vernacular that asserted a political voice into the developing field of contemporary Pacific art. Lisa Taouma writes that recurring motifs in Pule’s practice ‘. . . like the shark, fish, bird and flower, normally associated with sunny renditions of a happy island people’s flora and fauna, is effectively turned around to become macabre dreamlike visions of devouring surreal creatures. Now the icon of the cross has supplanted other Pacific Island symbols.’[5]

While the work is unique to a Niuean migation story, it speaks to universal questions around what we take with us when we leave a homeland, places or people. In looking back to this work again, it seems that equally as important as the question of what we take with us when we leave is what we wish to leave behind for those to whom may follow. Take these with you with you leave does both, providing a map that patterns genealogies, journeys, stories and a way forward by looking to the past.

[1] Caroline Vercoe, ‘Art Niu Sila: Contemporary Pacific Art in New Zealand’ in Pacific art Niu Sila: The Pacific Dimension of Contemporary Art in New ZealandAarts, Te Papa Press, Wellington, 2002, p 202.

[2] Peter Brunt, ‘History and Imagination in the Art of John Pule’ in Hauaga: The Art of John Pule, Otago University Press in assocation with City Gallery Wellington, Dunedin and Wellington, 2010, p 83.

[3] As above.

[4] As above.

[5] Lisa Taouma, ‘John Pule: Living in the City Ain’t So bad’ in John Pule: Mamakava, Adam Art Gallery Te Pataka Adam Art Gallery Te Pātaka Toi, Wellington, circa 1999, np.