Wednesday 14 September 2011

Ron Brownson

I invited Richard Wolfe to contribute a eulogy for Dennis Turner for the Gallery’s blog. Dennis’s painting Main Street 1939-45 is currently on exhibition.

Ron Brownson

“Wanganui-born artist and illustrator Dennis Turner recently died in London. His drawing ability was apparent at a young age, and a lifelong interest in Maori art began when he visited the homes of school friends at Wanganui’s Putiki Pa. By 1942 Turner had moved to Wellington and met photographer Tom Hutchins (later photography lecturer at the Elam School of Fine Arts, Auckland), who introduced him to artists Gordon Walters and Theo Schoon. All three had a profound effect on the young Turner, and shared his interest in non-European art. Schoon was about to investigate early Maori rock art sites in the South Island, and his records would inspire Turner’s own ‘Oceanic’ images. When first exhibited in 1951 these were described as ‘the link between the past and future that New Zealand painting has been needing.’

In 1942, the 18-year-old Turner became liable for military service. As a conscientious objector, he attempted to evade the call-up by changing his middle name from Keith to Knight, which he used as his signature. An abhorrence of war was expressed in his chilling image of dead bodies piled up in a blitzed cityscape, Main Street 1939-45. This painting is included in one of the opening exhibitions in the refurbished Auckland Art Gallery, which may be the first time it has been seen publicly for 63 years, since Turner’s first one-man show at the Auckland Society of Arts in 1948.

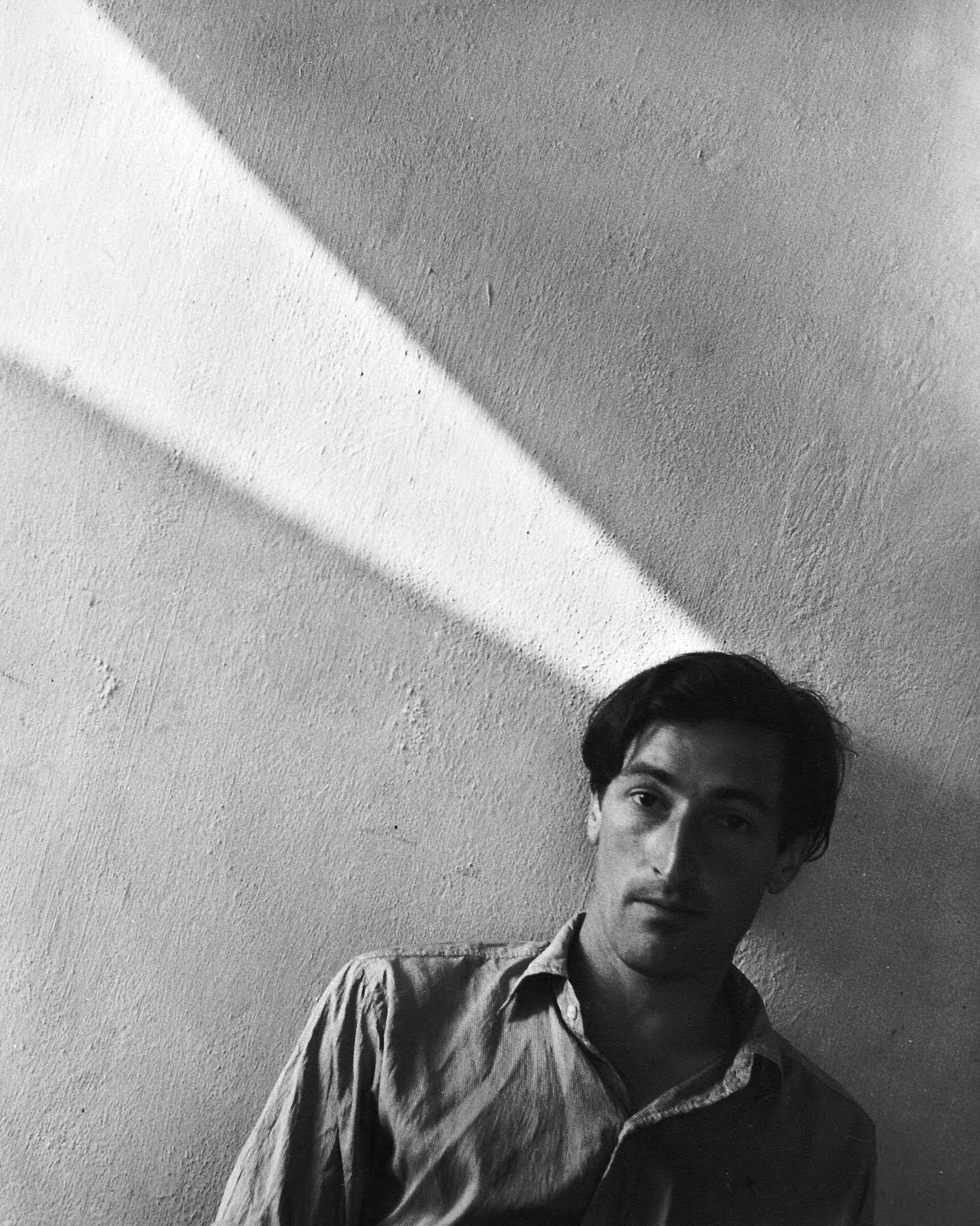

Turner was adept at capturing a quick likeness, and produced a large number of portraits. Among these were members of Auckland’s artistic community; writers R.A.K. Mason, Frank Sargeson and D’Arcy Cresswell, cultural historian Eric McCormick, architect Vernon Brown, photographer Clifton Firth and fellow painter Keith Patterson. Turner also provided illustrations for a wide range of publications, and in 1951 his mural for a Karangahape Road motorcycle shop became a cause célèbre. The artist fell victim to the draconian laws of the day, and he was prosecuted for working in public view on a Sunday.

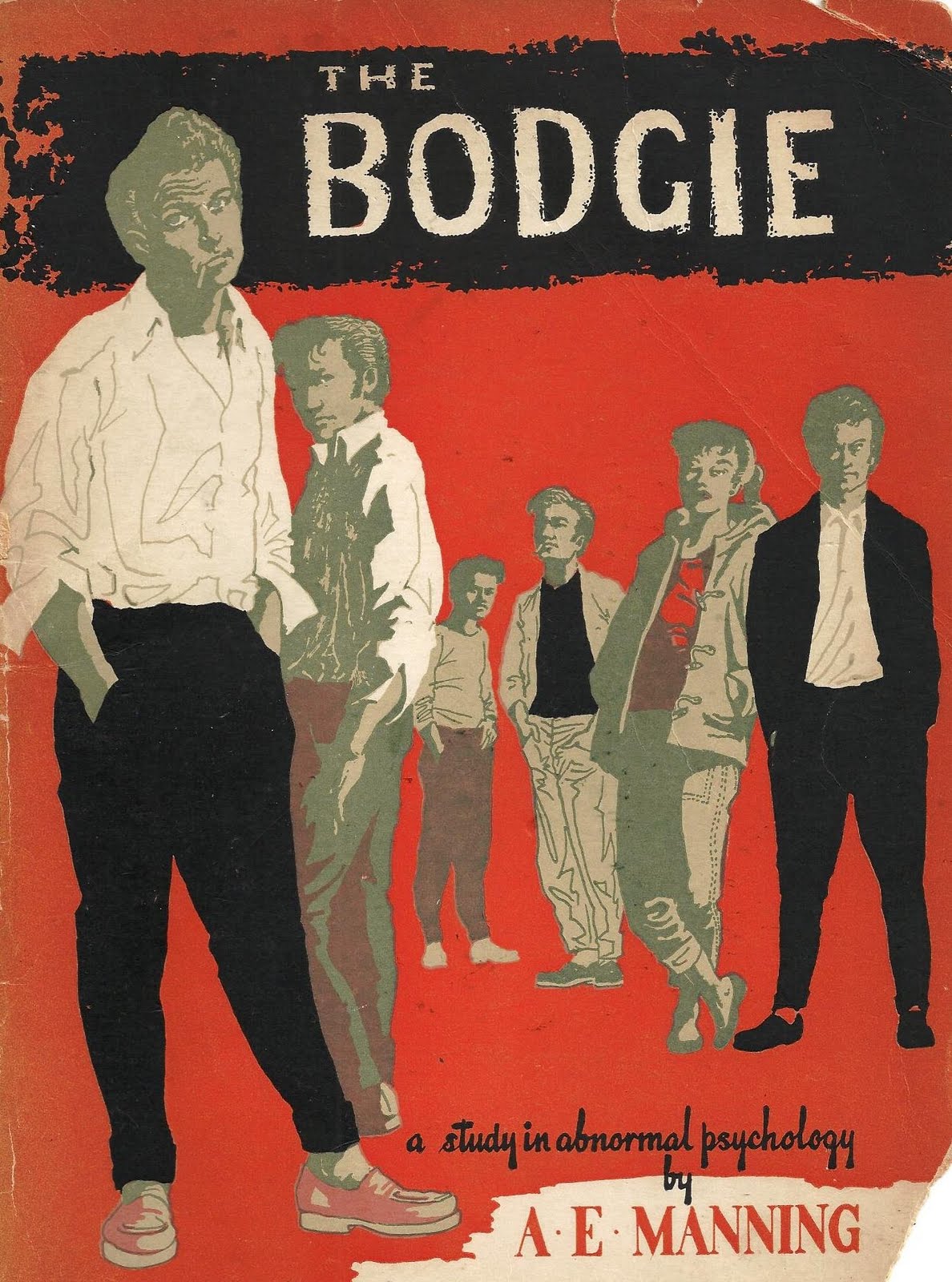

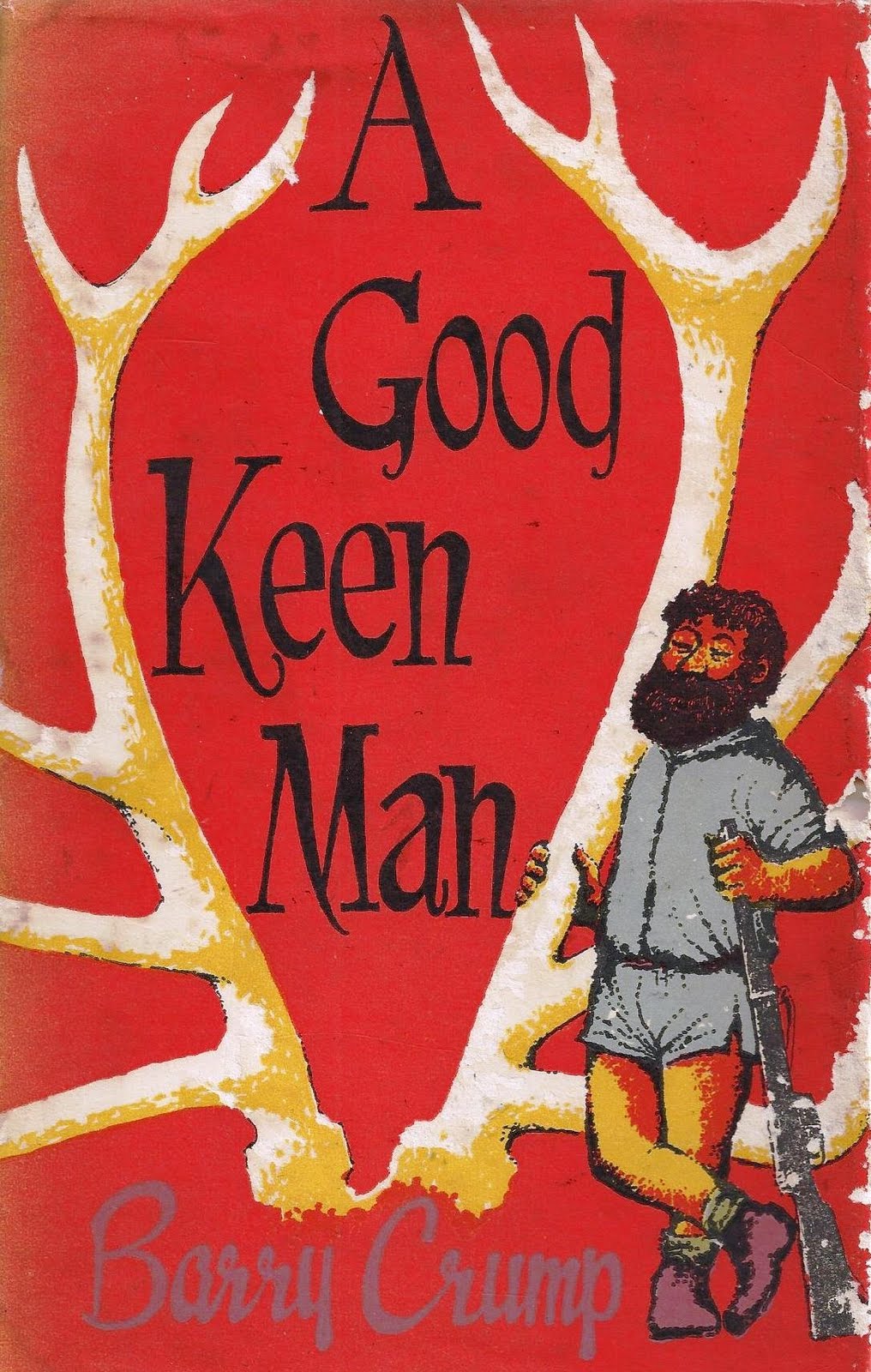

Around 1952 Turner left Auckland to work as a guide at the Waitomo Caves. Whilst there he met Ray Richards, of publishers A.H. & A.W. Reed, who later approached him to illustrate James McNeish’s book on pubs, Tavern in the Town (1957). This was the first of many such commissions, which included the first four novels by Barry Crump. Turner’s mastery of the medium and ability to capture human emotions and activities was also showcased in The Bodgie (1958) and the landmark Tangi (1963), an unprecedented sequence of images without text.

At Waitomo Turner painted his first landscapes. He avoided the picturesque for the otherwise overlooked New Zealand, of gorse, cabbage trees, burnt hills and cream cans. By 1956 he had returned north and was about to be labeled ‘Auckland’s most versatile artist’. In all he had some 25 one-man shows, and was included in six group and survey exhibitions at the Auckland Art Gallery. One of those was ‘New Zealand Caves’, a three-person show in 1959 that also included his old friend Theo Schoon. In 1962 Turner offered another rural perspective with his Sheep and Shearers series, followed by Hone Heke attacking the flagpole at Kororareka in 1845. Then, disappointed at the lack of response to his 1963 Landscape Headsexhibition, he sailed for England. However, the London scene had now been overtaken by the arrival of Pop Art. Unable to interest dealer galleries in his paintings, Turner resorted to commercial work to earn a living.

Turner felt New Zealand did not appreciate its artists, and made what Kevin Ireland described as ‘quite a noisy exit’ from the country. He only came back once, in 1992, for the Tylee Cottage residency administered by the Sarjeant Gallery in his home town of Wanganui. Whilst there he continued his engagement with Maori art and exhibited his Tiki series, which were met with accusations of cultural appropriation. Nevertheless, Turner’s search for universal symbolism continued, leading to what would be his final series, the Signs. In 1992 he was also included in two major survey exhibitions; the touring Headlands: Thinking Through New Zealand Art, and the Auckland Art Gallery’s 1950s Show.

Against all odds, the indefatigable and self-taught Dennis Turner was determined to make a living as a serious painter in New Zealand. In the process he produced a large number of original and insightful images into the national character, his subjects ranging from dying tree ferns and milk bar cowboys to black-singleted shearers and a renegade Ngapuhi chief.”

Richard Wolfe