Wednesday 3 Novemer 2010

Ron Brownson

I have already secured two Ben Cauchi photographs for the Gallery’s collection. The Chartwell Trust have acquired three examples of his beguiling art. Looking at these images again, I realised I should invite Ben to comment on his work. Ben sensibly noted that artist’s statements have a “habit of becoming definitive.” So, these are not final words on his images, just some recent words to mix with mine.

Certain photographs remain within you long after they are seen before your eyes. Peter Ireland has alluded to this fact on a number of occasions in his telling writings about the image-driven impact that results from photography's presence.

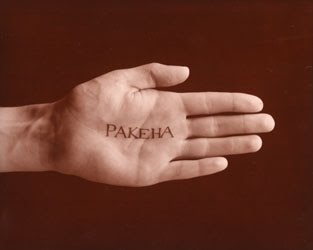

For me, Ben’s images have an hypnagogic intensity – once seen, never forgotten. The quality I call wall power! They are gifts to place in one’s imaginative picture library. I look at Ben Cauchi’s Loaded Palm in this way. The photograph has a palpable and votive presence; it resonates just like sentences written by Samuel Beckett:

“Memories are killing. So you must not think of certain things, of those that are dear to you, or rather you must think of them, for if you don’t there is the danger of finding them, in your mind, little by little.”

Samuel Beckett, The Expelled, 1946

One is offered the man’s palm not in a gesture of greeting but as visual evidence of a branding with text. Ethnic branding. Instead of pain, here is a tender declaration of the well-known word that carries so much meaning here in Aotearoa New Zealand – it is our word - PAKEHA.

I recall the first recorded written usage of Pakeha occurred in a letter written by William Hall to the Church Missionary Society on the 15 June 1814 -“They…expressed their joy by saying ‘Nuee nuee rangateeda pakeha – a very great Gentleman white man’.”

The sepia tone of Loaded Palm lets the work feel antique, like a visual relic from the 19th century. The photograph is imbued with another period by the hand being silhouetted against its seamless background. The hand’s action puts this hand's action in active conversation with the past.

“Loaded Palm was one of a suite of 10 photographs I made shortly after deciding to leave tertiary study and attempt an existence doing what I wanted to do. I called the suite, none too subtlety, Building the Empire. It wasn’t just an exuberant attempt at positive visualisation; I was referring more specifically to various histories, both real and constructed, and trying to draw links between them. With this one, I was particularly interested in branded identity - both in terms of local historical traditions and also thinking of the well known Southworth and Hawes daguerreotype of a branded hand (something I revisited a few years later with a tintype called The Photographer's Hand). The left hand is significant as it afforded the right to print neatly.”

Ben Cauchi

Loaded Palm is doubly 'loaded' because of its dialogue with Southworth and Hawes sixth-plate daguerreotype of Captain Jonathan Walker’s branded hand of August 1845 (the hand is branded with SS, for ‘slave saviour’ or ‘slave steeler’ as Walker had helped 7 African American men to gain their ‘Life, Liberty and Happiness’). Ben's aspect of referencing a backstory, a parallel narrative, is what singles his work out for visual exchange. Loaded Palm is both a potent indictment and an affirmation, evidence and recognition. A palimpsest expressed by the action of an open hand.

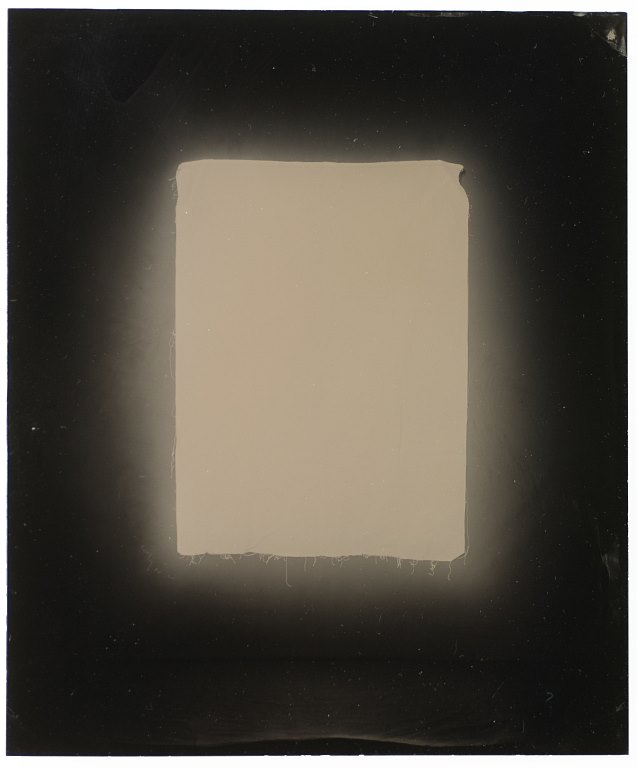

Loose Canvas has an exquisite ambiguity. Are we looking at a miniature textile radiant with light? Or is it a larger weaving that is acting like a lamp, a veil of illumination. The canvas looks back lit, is this canvas hung against a window within a room shadowed by its own darkness? The canvas needs the surrounding murkiness to be what it is, a draped bright sentinel. Always the question remains, what is behind this light?

Light, as a subject and an effect, are always put to terrific use in Ben’s photographs. Never more eloquently than in Loose Canvas. Like the veil of Saint Veronica, this textile acts like a rectangular oriole and sacred nimbus. It reminds me of the meteorological effect known as the ‘occluded front’, where you are physically close to something but cannot ascertain the nature of its reality.

“Loose Canvas is not about any one thing in particular – and more specifically, isn’t really about what it says it is. The object in the photograph has it’s own qualities, which is fine. Generally, though, what I am more interested in is how something works symbolically. With this one in particular, the main focus for me was Light as a subject in it’s own right. That and the lack of anything else.”

Ben Cauchi

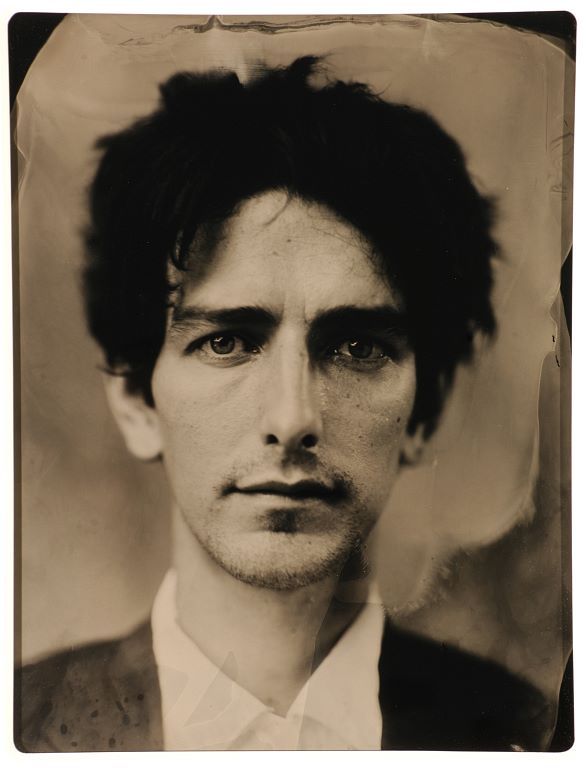

It took me some years to find Ben’s Self-portrait. Not any self-portrait, as I have seen quite a few of them, but the one that had to be 'captured' for Auckland Art Gallery. The perfectly suited public instance of visual memory living on as a self-encounter. The Gallery has not collected many self-portraits and very few by artists who are living now.

I wanted one of Ben’s self-portrait’s that had the equivocation and enigma that I so admire in his images of himself. They appear to echo the compositional rules of a mug shot – close-up, somewhat confrontational, and physiognomic in their remit to record appearance before personality. Yet, there is plenty of personality in this self-portrait, because it is near to a meeting with the artist’s own doppelganger. Knowing the Self-portrait before I met the artist I surprised myself by not recognising Ben in real life. I thought "you are not your self portrait."

“In terms of the Self-portrait, it was one of two plates I made that day. I was in the middle of an 8-month residency in Whanganui. It was going well, although I think the temporary nature of that environment can play on one’s mind slightly (not that that's necessarily a bad thing). At the time, I was thinking of Salvator Rosa’s Self-portrait held in the National Gallery in London. I particularly like the inscription in the bottom corner of the painting Aut tace aut loquere meliora silentio which roughly translates as either be silent or speak better than silence, in other words, shut up or say something useful. It's a good motto. The sentiment eventually grew into this tintype Say nothing (2008), an alternative approach.”

Ben Cauchi

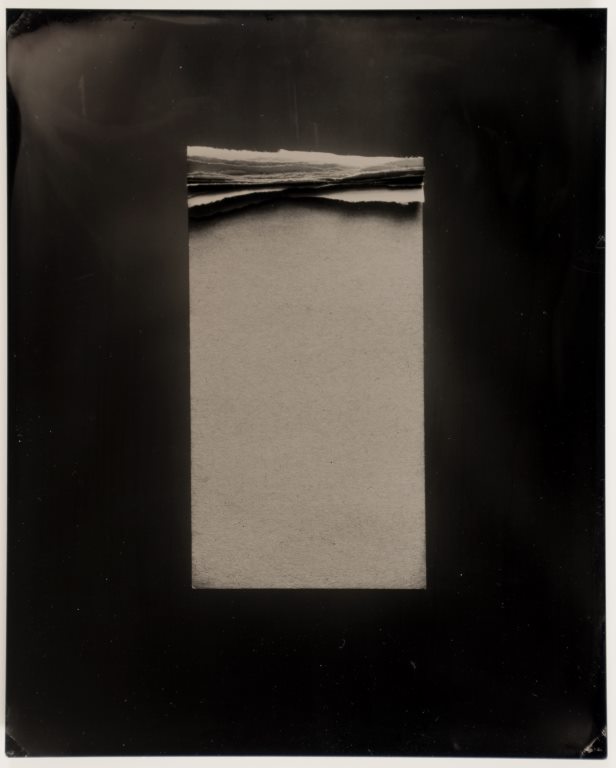

A Remnant, from 2009, shows, Ben tells me, "the cardboard base for a notepad." It seems old and fragmentary. A noble ruin in its most modest incarnation; here we encounter the remains of what has once been written on. As with all his photography, time pervades the image as if it is both weighted and weightless. This top-lit detritus has mysterious import. Why keep it other than to photograph it as cast-off residue? Of what?

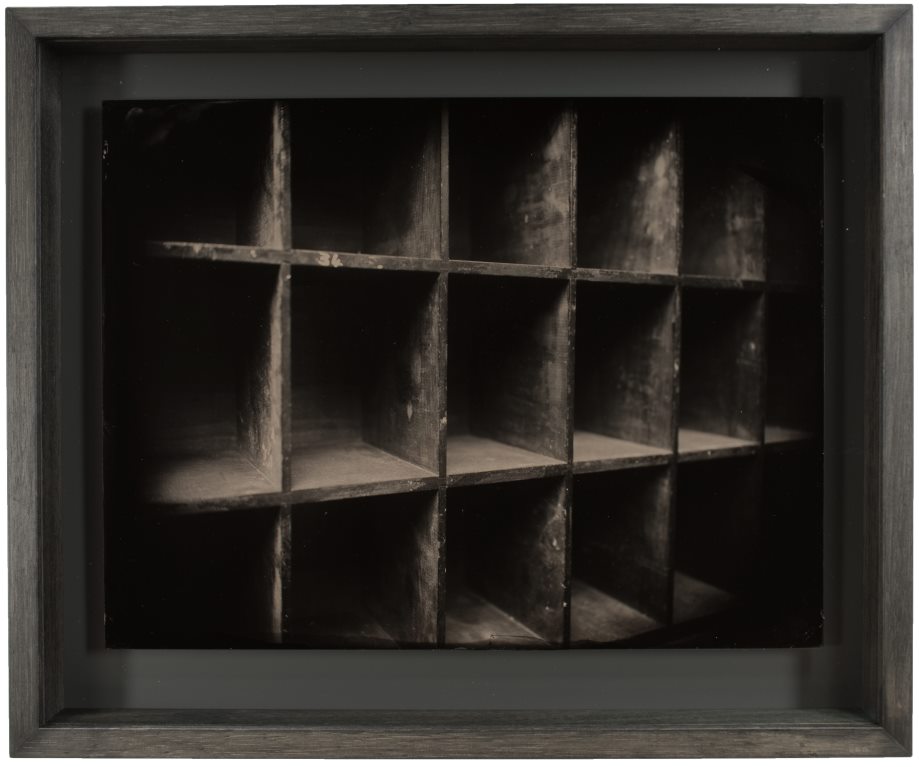

The Way of All Things is suffused with what I call the melancholy of lost storage. My home is filled with such age, patina and sculptural presence which is always more important to me than mere function and daily practicality. Yet, these old cubbyholes have been useful to many people but have not seen any letters or messages for years. They wait like ‘saints and martyrs’, to gloss T.S. Eliot.

Ben’s point of view is always as potent as his presentation – here boxes self-repeat themselves within a box frame. It is a theatrical trope, as is much of his work, but this image is theatrical because it is not fabricated to be photographed, as some of his other photographs are. That old phrase "the dead letter" office comes to mind. Second from the left at top, one of these niches is inscribed with the number 34; none of the other units is numbered. What has have been the uses of cubbyhole 34?

I noted earlier the parallels I feel between Ben's photographs and the writings of Samuel Beckett. Sam is frequently misperceived as an absurdist but is, actually a realist infected with three interwoven creative strains, all of which are devoid of sentimentality: melancholy, nostalgia, memory.

It seems to me that Ben Cauchi’s wonderful images inhabit a parallel territory grasping life and bringing a mirror to its surface to declare imitatio vitae, speculum consuetudinis, imago veritatis. The drama within these images is a mirror of human behavior, an image of human truth.

Samuel Beckett put this visual affirmation of encounter another way, but it is equally convincing: “Enough. Sudden enough. Sudden all far. No move and sudden all far. All least. Three pins. One pinhole. In dimmost dim. Vasts apart. At bounds of boundless void. Whence no farther. Best worse no farther. Nohow less. Nohow worse. Nohow naught. Nohow on.”

Samuel Beckett, Worstward Ho, 1983

Ben Cauchi makes photographs that I never ignore. They are already some of the key photographs made in Aotearoa.

Captions

Loaded Palm 2002-2006

gold toned printing out paper print

200 x 250mm

Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki

purchased 2006

2006/21/2

Loose Canvas 2007

tintype

240 x 200mm

Chartwell Collection, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki

purchased 2009

C2009/1/1

Self-portrait 2005

ambrotype

350 x 270mm

Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki

purchased 2006

2006/21/1

A Remnant 2009

wet collodion on acrylic

510 x 425mm

Chartwell Collection, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki

purchased 2010

C2010/1/29/2

The Way of All Things 2010

wet collodion on acrylic

274 x 360mm

Chartwell Collection, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki

purchased 2010

C2010/1/29/1