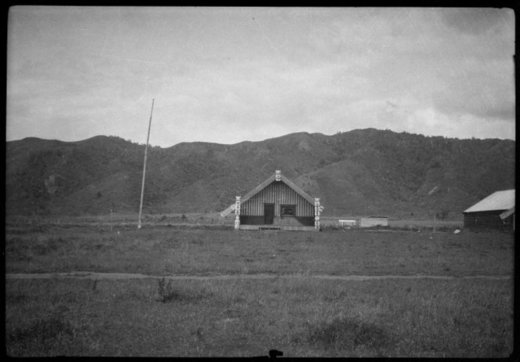

Kuramihirangi meeting house, Te Rewarewa Marae, Ruatoki, Date unknown

Reference Number: 1/4-002747-F. Taken by an unidentified photographer. Date unknown. National Library of New Zealand

Arnold Manaaki Wilson was born and died in the Year of the Dragon. He would say he had a good life, and he did, as great taniwha do. He iti na Tūhoe, e kata te po.[1]

Arnold lived outside of his Tūhoe homeland for 65-plus years and built extensive relationships with individuals, whanau, hapu, communities and iwi who loved him. The kōrero and knowledge of Arnold’s achievements reside with the people of these places and with his wife Rangitinia and their whanau. Arnold’s early life, however, is not widely known outside intimate circles. His early childhood gives insights into the type of life training he obtained from his people, and by whanau accounts, many handbooks could be written on how this taniwha was trained.

Arnold’s final return home to Te Rewarewa Marae in Ruatoki was greeted with the elders recounting that Arnold left home aged 11 years under sad circumstances to rise above the difficulties and the realities of the time. They paid tribute to a son who became a vital and important figure in the arts and arts education in Aotearoa New Zealand. As he lay in state between the twin meeting houses Kuramihirangi and Te Rangimoaho (as depicted in the accompanying photo) I was warmed by the accuracy of elders and stunned but not surprised by the length of time Arnold had spent living away from his turangawaewae. It too quickly brought home to me, the years I have spent away from the same valley and what that says about contemporary times.

This is a summary of the early part of Arnold’s story to give some indication of the extraordinary life he lived. Arnold was born 11 December 1928 and raised by an exceptional cast of whanau members. He was the youngest member in a family of five children. His mother was Taiha Ngakewhi Te Wakaunua and his father Fredrick George Wilson. His siblings were Te Waiarangi, Hoki, Fredrick and Thomas.

Arnold’s mother's father, Heteraka Te Wakaunua, was a charismatic political visionary leader for Te Mahurehure and Ngāti Rongo hapu – indeed for all Tūhoe. Like other tribal leaders, Te Wakaunua placed a high value on whanaungatanga (kinship), manaakitanga (respect & kindness), aroha ki te tangata (care for people), matemateāone (yearning) and the social and political wellbeing of his people. Arnoldmaintained these values throughout his life as we can see this in the way he titled some of his sculptures.[2] A carved pou of his grandfather Te Wakaunua holds a prominent position on the poho (porch) of Te Rangimoaho wharenui.

Arnold’s childhood patterns changed with the death of his mother during the great flu epidemic of the 1930s, when he was aged five. His paternal grandmother took charge of his care and life. To keep the memory of his mother alive and the legacy of his grandfather as a touchstone in his life, Arnold would be addressed as Te Wakaunua, as if he were his grandfather. His grandmother Mariana Creek-Wilson passed away when he was 11 years old and from then Arnold became a whāngai, whereby the wider Wilson whānau assumed responsibility for him. Mariana Creek-Wilson was from the Tokopa whānau of Ngāti Tarawhai. Arnold’s paternal grandmother was Tuihi Tokapa.

Arnold’s early schooling at Ruatoki Native School focused on the three R’s – reading, writing and arithmetic – and spoken Māori was forbidden in the classroom and playground. All year round school uniforms for boys were gumboots and long pant dungarees or what Arnold and his schoolmates called ‘kumfoot and tungaree’ Spinning potaka[3] with flax and playing marbles were favourite playground activities for boys as was eeling in the river. The schoolmaster and senior boys were the local barbers for students in the community. The students grew most of the eucalyptus, pine and lawsonianas planted in the community, which they tended from seedlings. Childhood playmates were whanau and became life-long friends.

Arnold’s childhood was similar to many whānau in rural communities in the 1930s. When a major project needed attending to the whārua (entire community) rallied. Planting willow trees on the banks of the Ohinemataroa was one of those community efforts to keep the river from taking the land. Arnold played his part planting the banks with willow nearby Te Rewarewa with his father. This planting also protected the favourite swimming hole of the children located under the RuatokiBridge.

Arnold’s whānau were hard working and community-minded people. The Wilsonsowned and operated the local bakery-come-grocery store, the bowling green, billiard hall and the Ruatoki tennis courts. These amenities became important meeting places in the community and served to familiarise the population to the world beyond Ruatoki. Opposite the Wilsons shop was a larger trading post, named for the family who owned and operated the business. It was called the Middlemas shop and it housed the Post Office. Another smaller, no less important trading concern was owned and operated by my great grandfather, Wiremu Tereina from Ruatahuna, who married my great grandmother Pihitahi Wharetuna. His store was a favourite place for children for the range of boiled lollies he would stock. Wiremu went on to start the first a bus service for the Ruatoki community and his bus was named Te Kauru.

Arnold was a star student at Ruatoki Native School and his artistic abilities were recognised by head teacher Mr Hans Hauesler. During the tangi, Aunty Anituatua Black recalled how she and younger cousins admired Arnold’s drawing abilities. He would draw using pencil or chalk and copy images sourced from postcards and visual material supplied by Mr Hauesler. Often these images were of things he had not yet seen in real life including images of English garden flowers such as hollyhocks in snow scenes. Another mentor from Ruatoki School was Mr Arthur Boswell who was very gentlemanly and a stickler for getting things right. WhenArnold was not drawing, he would could be found working in the family garden, milking cows or attending the orchard. His personhood and worldview was shaped by many relationships inside Ruatoki and by individuals, extended family and the wider Tūhoe community.

These are among my favourite memories and conversations I shared with Arnold. He was a great storyteller, supporter and beloved uncle who always saw the positive in all things and all people. As an auspicious full moon watched over the tangi proceedings and followed the bereaved whanau back to Auckland I felt I was witness to ancestral wisdom through the saying, Kua tae koe ki Paerau te huinga o te kahurangi’ – You have arrived at the great meeting place of the ancestors.

[1] He iti na Tūhoe e kata te po - A few Tūhoe and the underworld laughs. This means a few Tūhoe are the equal of many from another tribe.

[2] He Tangata He Tangata, Tane Mahuta, Te Tu a Te Wahine etc

[3] A potaka is a spinning top either carved from totara or kauri, or fashioned from pinecones.