Producers of art history—whether curators, writers, or institutions—have a responsibility to rake over the past, thinking about what might have been missed or downplayed, and to actively foster the remembering of that which deserves to be more widely and deeply known than it already is. More familiar artists and narratives are more frequently presented, and more frequently presented artists and narratives become more familiar. When a grand new exhibition is mounted of work by Colin McCahon, new audiences meet him and his position in the canon is strengthened. Memory comes from iteration. This is clear. Just as clear, I hope, is the fact that a lack of iteration threatens memory. With limited exposure, artists like, say, Malcolm Harrison and Douglas MacDiarmid, stay niche.

There is a temptation to look at the present moment as a positive one for LGBTQ+ and takatāpui communities in Aotearoa. Our members are, no doubt, experiencing a relatively high degree of freedom and visibility, including in the art world. New Zealand’s next representative at the Venice Biennale, Yuki Kihara, is also our first non-binary representative. Established artists like Fiona Clark and Lonnie Hutchinson continue to grow in renown. Younger artists are making their mark with practices that speak about queerness or take it as a given: Owen Connors, Laura Duffy, Tanu Gago, Ayesha Green, Robbie Handcock, Ana Iti, Areez Katki, Sione Tuívailala Monū, Elisabeth Pointon, Cass Power, Pati Solomona Tyrell, Christopher Ulutupu, and Aliyah Winter, to name but a few.

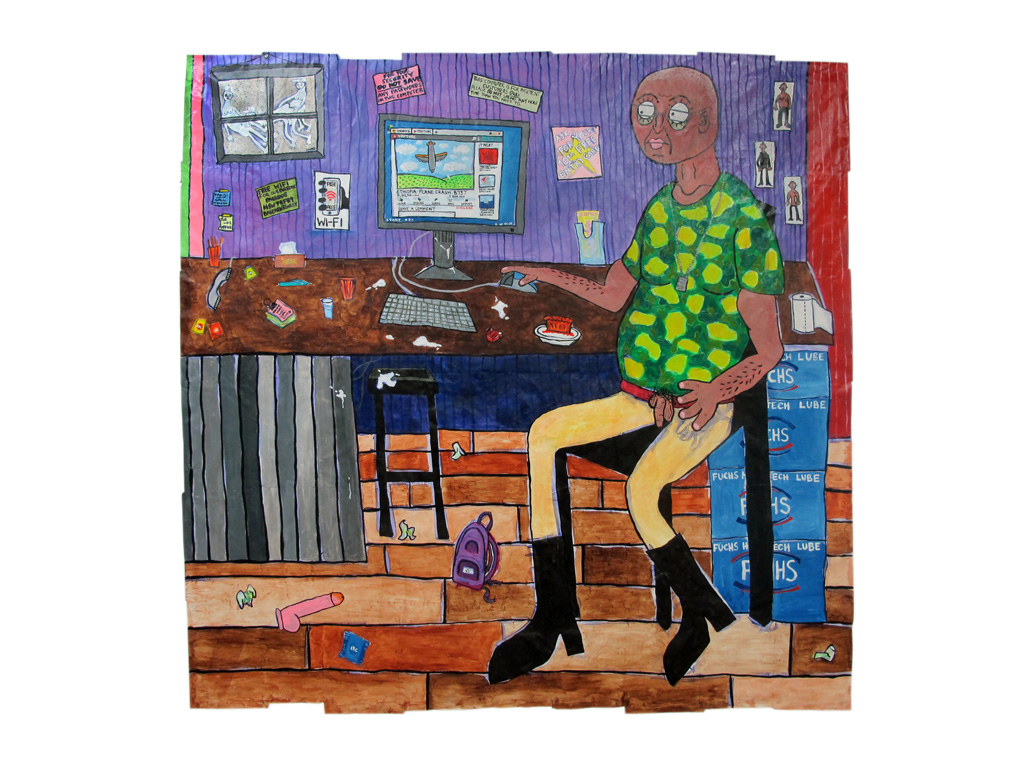

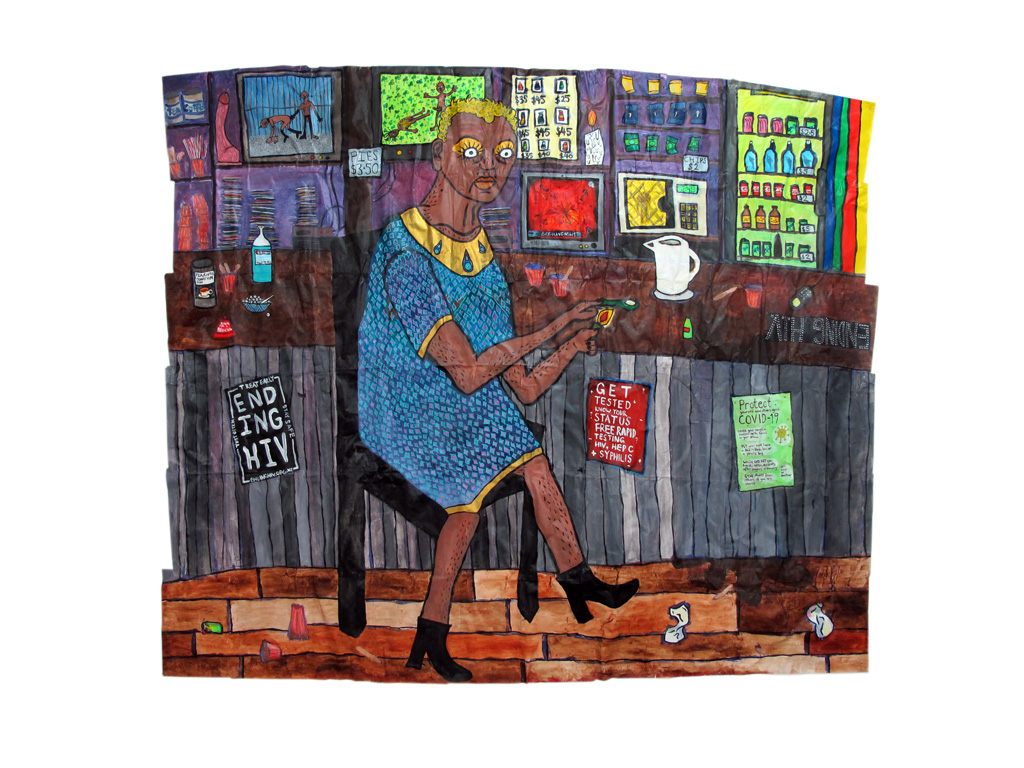

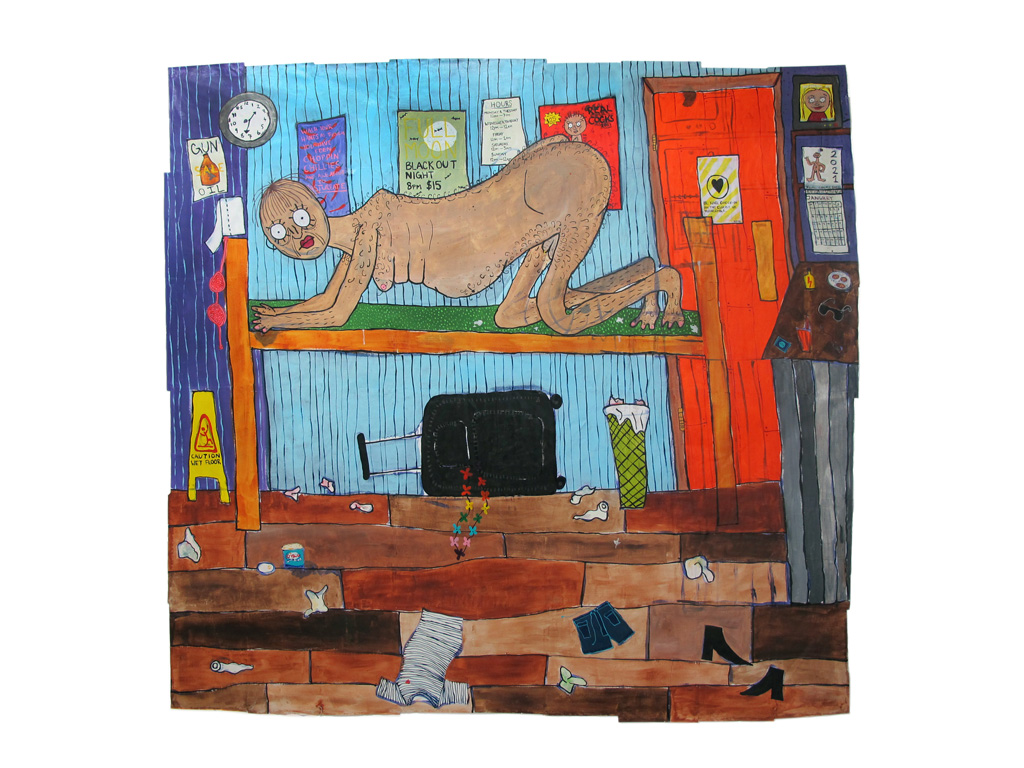

This state of affairs instils pride and, indeed, optimism. Nevertheless, I am circumspect. There remains a risk that celebrations of queer artists and artworks will be few, fitful, and on a relatively modest scale, that they will fall by the historical wayside more easily than that which derives from and shores up the mainstream. Visiting Thirsty Work and Urban Nothing, I felt not only excitement at seeing excellent works released into the world, but also a renewed sense that such works need to be shown again and again, widely, in institutional spaces big as well as small. They must not be slid into the racks and left there—products of a moment remembered only in that moment.