Friday 26 November 2010

Ron Brownson

In 1958, the Gallery’s then Director, Peter Tomory, prepared the important exhibition – A Private Collection of New Zealand Paintings - which sampled the collection of artworks that Charles Brasch and Rodney Kennedy had gathered over many years at Dunedin.

Here is a link to the exhibition’s catalogue held in the E.H.McCormick Research Library. This is one of the earliest catalogues to document a private art collection in New Zealand:

http://www.aucklandartgallery.com/media/166436/cat21.pdf

I thought that it is now time to profile Peter Tomory’s introductory remarks and re-present the excellent essay that the Gallery commissioned from Charles Brasch. He raises issues about contemporary art that are still being discussed.

Professor Paul Millar is currently preparing the official biography of Charles Brasch and Dr Peter Simpson has recently published a terrific account of the association that this esteemed poet, editor and collector had with Colin McCahon.

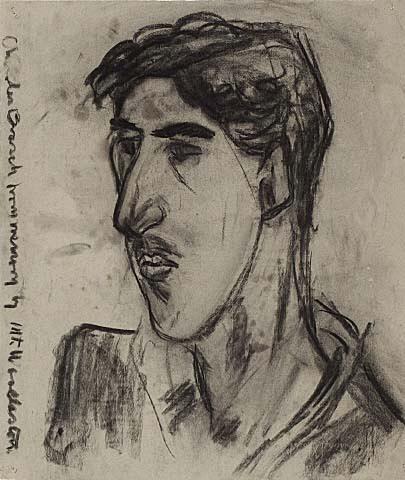

M T Woollaston, Charles Brasch from memory

1938, charcoal

Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, gift of Mr Colin McCahon, 1961

I am very grateful to Alan Roddick and to the Estate of Charles Brasch for permission to re-publish Brasch’s essay. They generously agreed with me in recognising that Charles’ essay needed to be more accessible.

FOREWORD

Charles Brasch and Rodney Kennedy have been acquiring pictures for many years so that now their collection is certainly the most extensive and carefully chosen in the Dominion. Like all private collections it exhibits the collectors' taste, but apart from this it is a matter of some gratification both to the artists and all those interested in the furtherance of serious art in New Zealand to find at least one collection which demonstrates both the judgement of its owners and the confidence they have in the painters of their own land. We are most grateful to Mr Brasch and Mr Kennedy for selecting the pictures and very generously lending them for this exhibition.

P. A. TOMORY

August 1958

INTRODUCTION

The first foreshadowings of what we may now venture to call the New Zealand imagination, although as yet we can only perceive it dimly, began to appear some thirty years ago. A century of European settlement had laid at least a foundation of history and experience in our small contained world; more than one generation had grown up accepting this foundation as their own, and thinking of life on these islands, poor though it might be in the amenities of civilization, as in no way unusual, but simply as life itself. On that foundation of the ordinary and everyday, New Zealanders at last began to build themselves a shelter for their as yet homeless imagination.

A country or a people does not properly exist until it has created its own imaginative world. Men need that world if they are to live fully and well in

the everyday world, for the everyday alone never satisfies them. They are impelled to seek, in the imagery of words, forms, colours, rhythms, a perfected

life more shapely and profound and intense than their outward daily lives, one in which they may discover recollections and prophecies, visions and fulfilments, of all that they think and feel and imagine, all that they hear and see, in those moments when their sense of life is at its deepest and keenest.

In the best New Zealand painting of today we may recognize some of the first works of imagination conceived in terms of the experience of life in New Zealand. They are not what we might have expected; but then works of imagination do not answer expectation — that is not their function; on the contrary, they habitually confound expectation; they are born to surprise and delight, to remake the common world instead of merely rehearsing it over and over again, to show us all we thought we knew in a wholly fresh light and with strange and moving significances; in short, to create, not to repeat.

The best contemporary painting (and literature, and music) is in fact creating New Zealand as a world of the imagination. This is a new development among us, which makes the present a particularly exciting and hopeful time to live in, because in these first stirrings of the native imagination an undiscovered world seems to be waking and opening before our eyes. In that world we may look for an expression of our spiritual identity as a people.

Earlier painting in New Zealand shows the country through the eyes of painters who saw the world as Europeans; their work forms what might be called our imaginative pre-history. Then come the painters who grew up in New Zealand yet painted like Europeans because they had been taught to approach painting as a European activity. It is only within the last thirty years or so that painters have taken for granted that painting is a New Zealand activity too, so that they interpret the world, literally everything they see, in New Zealand terms.

The pictures in this show include work of all three phases, but most of them belong to the last. They were not got together on a particular plan, with the idea of forming a collection; we bought such work as happened to come our way, and that interested us because it seemed to possess a certain imaginative quality; much of it was the work of our friends, which we were best able to follow. The show is thus in no way a representative one, and it includes no drawings; several of the best New Zealand painters of today (not to mention the past) are not represented in it, because we have not been lucky enough to come across good examples of their work.

Charles Brasch

It is useful to keep in mind what Charles Brasch wrote nearly eight years earlier about Colin McCahon’s landscapes of the immediate postwar years:

Their harshness, their frequent crudity, may seem shocking at first; but if we are honest with ourselves we have to admit that these qualities reflect with painful accuracy a rawness and harshness in New Zealand life which are too easily passed by or glossed over; a parallel may be found here with some of Frank Sargeson’s stories – and not his alone. There is a bitter and unpalatable truth in these paintings: they tell us something about ourselves which had not been made plain before.(Charles Brasch, ‘A note on the Work of Colin McCahon’, Landfall, volume 4, number 4, December 1950, page 338.)