Nearly two centuries later, in 2020, Fijian-born Lala Rolls directs the documentary Tupaia’s Endeavour, with artist Michel Tuffery who has ancestry from Sāmoa, Tahiti and the Cook Islands, and actor Kirk Torrance (Ngāti Kahungunu). In the documentary they visit Opoutama in the hope of seeing Tupaia’s rock drawings and speak to Anne Iranui McGuire, a local Te Aitanga-ā-Hauiti woman, who recalls seeing a drawing of a ship on a rock. It was ‘as a child would draw it,’ she explains, and had three masts and square sails. Maguire also remembers seeing drawings of something like sharks or whales.

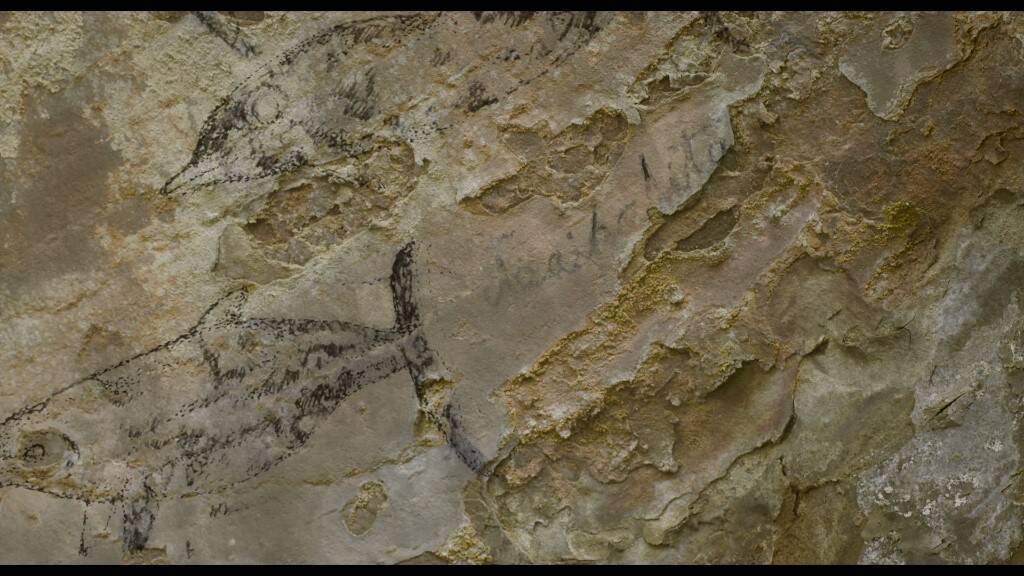

Tuffery and Torrance scan the surface of the rock but are disappointed to find only the merest hint of drawings on the rock. Almost at the point of giving up, one of the film crew sees something. It is part of a marine mammal’s tail and body, and a text. Rock art expert Nick Tupara visits the site and confirms the authenticity of the work as Tupaia’s, pointing to similarities with the watercolours he made, including the iconic image of a crayfish being traded with one of the Endeavour’s crew. Tupara reads out the letters from Tupaia’s writing: ‘a – i – h – e’ – aihe, the Māori word for dolphin.

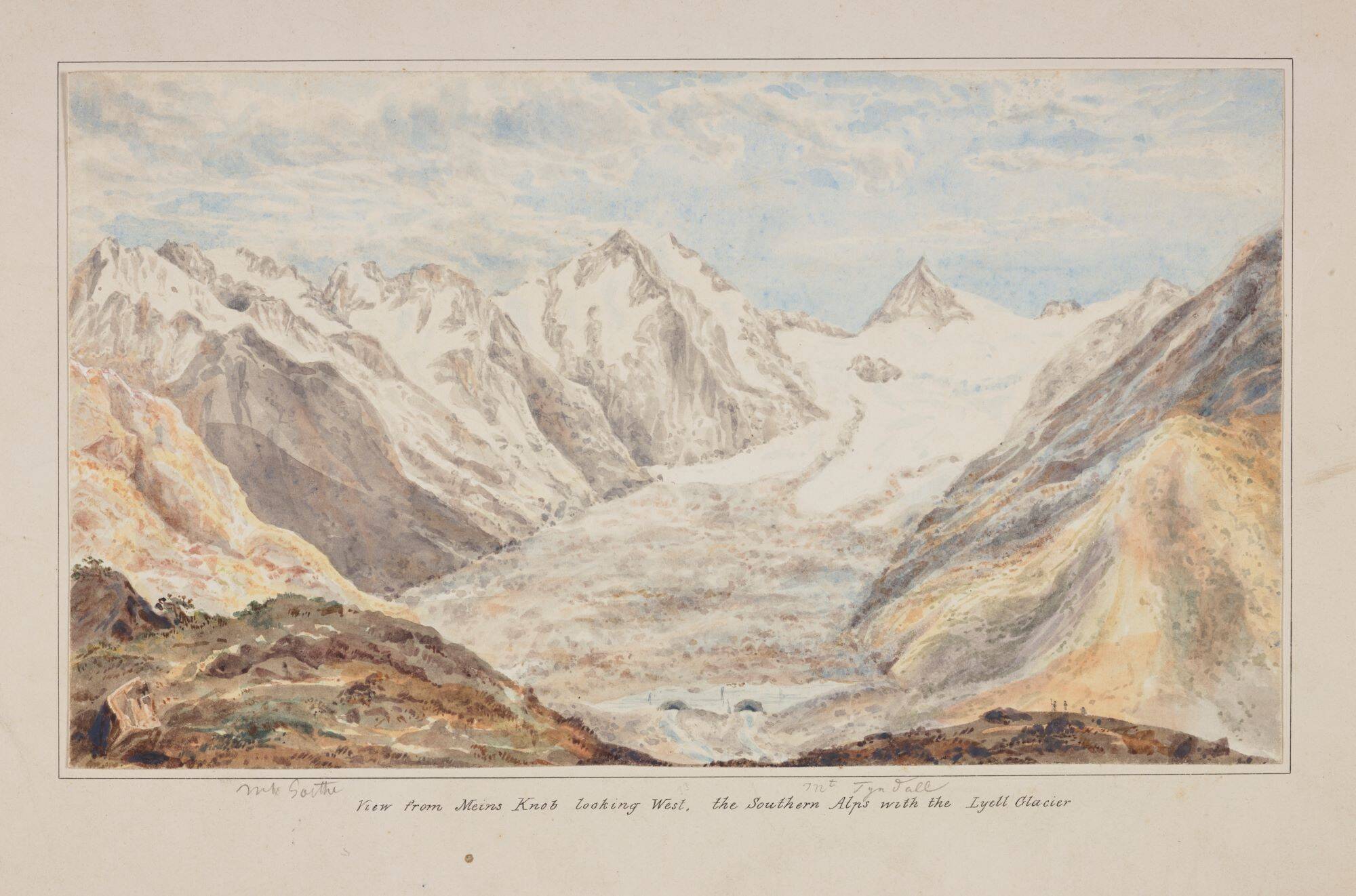

Having survived centuries, still visible in the living memory of Anne Iranui McGuire, Tupaia’s drawings have almost disappeared over recent decades. Rock art is a vulnerable art form, and even under overhangs like the Opoutama drawings the actions of the weather can be damaging. Environmental change is a pressing issue for rock drawings, including the hundreds of examples of rock art further south in Te Waipounamu, the South Island, some of which could be up to 1000 years old. Rock art is often made on porous surfaces, as on the limestone of the Te Waipounamu examples. Cautionary tales from Indonesia and Australia reveal the mounting effects of climate change on rock art.

Indonesia’s rock art has survived over 45,000 years, but in recent decades has been decaying. The images are flaking and blistering away from the rock surface, and scientific investigations have found that the reason is the growth of salt crystals, a process called haloclasty, in porous rocks like limestone. Salts are left behind on rocks after evaporation and swell and shrink with heating and cooling. The salts’ activity can cause the rock to crumble, or to create small columns between layers, essentially lifting the drawings away from the rock surface. The climate crisis is amplified in the tropics, where wetting and drying periods are intensifying, causing the salt crystal actions to become more devastating for rock art in this region. Humidity is increasing, because more water is being detained on land, allowing the salt crystals to keep swelling over longer time periods.

Across the Tasman, in Australia, it is fire that is damaging rock art. Extensive fires throughout Queensland, New South Wales and Victoria in 2020 destroyed millions of hectares of vegetation and unknown numbers of Aboriginal sites. The radiant heat from fires can directly damage the surface of rock and destroy drawings, and soot has also caused indirect damage to rock art. Even the measures put in place to protect rock art can become destructive when fire is involved. Recycled plastic walkways installed to protect rock art at Baloon Cave in Queensland’s Carnarvon Gorge exploded into fireballs when fires reached the site in 2018. The same thing had happened at the Keep River rock art site in the Northern Territory, where the heat from a burning plastic walkway was so intense that the rock crumbled, taking the artwork with it. It is believed that the hand-stencilled images could have survived the fires if not for the intense flames from the walkways, or the water damage from the steam released from their burning plastic boards.