—

exhibition Details

Emerging in America in the 1960s, Minimalist Art took in the sculptures of Carl Andre, Dan Flavin, Donald Judd, Robert Morris, Richard Serra and Tony Smith; and the paintings of Frank Stella, Ellsworth Kelly and others. The Minimalists banished abstract expressionist gesturalism - the hand of the artist - in favour of non-hierarchical, mathematically regular, grid-based forms, and literal, impersonal, even industrial surfaces. Minimalism was aligned with phenomenology: its simple, serial structures served to emphasise subtle changes in perception as the spectator's viewpoint shifted in time and space. In America, Minimalism arrived in almost the same breath as Pop Art, also reacting against heroic Abstract Expressionism. But, while Pop countered AbEx by plunging into the everyday, minimalism went the other way, absenting itself further, obliterating external references, becoming more rarefied. At least that's how the story went.

In recent years Minimalism has been positioned by key American museums, particularly the Guggenheim and the DIA Foundation, as the most important American postwar art movement. Consequently it no longer seems like a reaction to a prevailing idea of how art should be; it has become the prevailing idea, art's new commonsense. Minimalism has deeply effected contemporary taste, our expectation of how art should be. And yet these days we approach Minimalism quite differently, less phenomenologically, more semiologically. Although in the 1960s Minimalism aimed to suppress associations, in the postmodern 1980s we were instructed to rethink even the most abstract work as text. Today we recognise minimalist art as a covert form of representation, referencing the abstract logic of the modern world, ironically making it akin to Pop. This idea makes sense of the famous epiphany the Minimalist sculptor Tony Smith reported experiencing. During a nighttime ride on the unfinished New Jersey turnpike in the early 1950s, Smith was blown away by its power and mystery, realising such new artificial landscapes embodied an experience art had yet to capture.

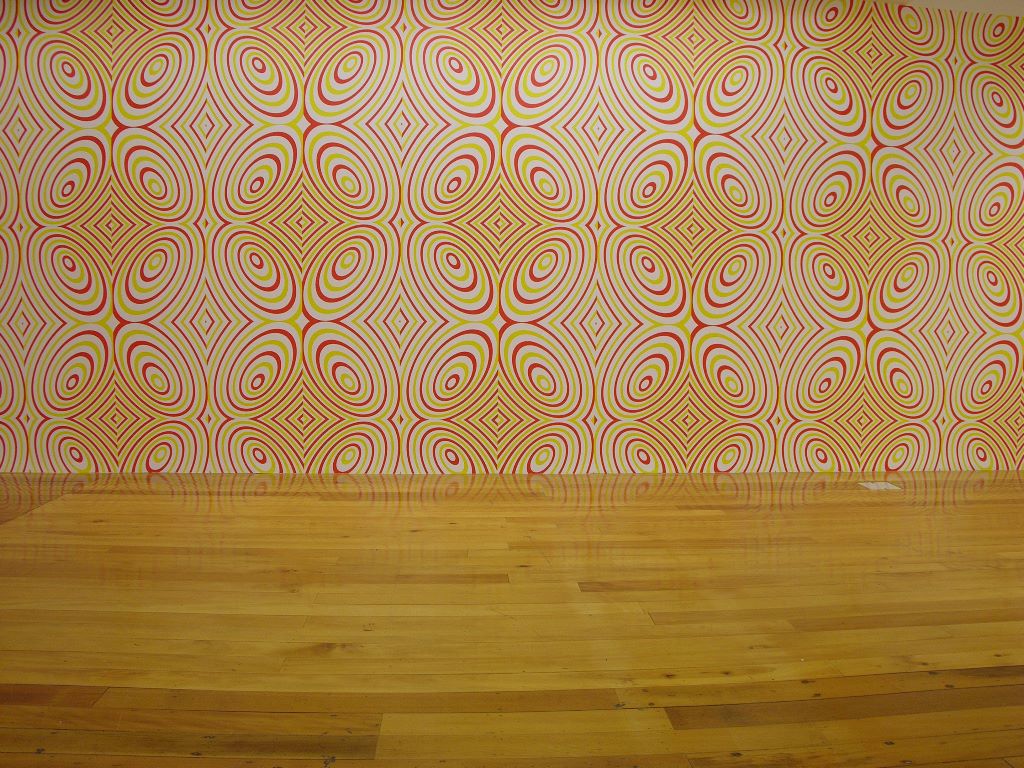

Since the 1970s many artists have reprised Minimalist art, lacing it with all sorts of references. In New Zealand this idea is well represented by the Auckland artist Jim Speers, and his odd infusion of Pop and Minimalism. Speers muddies the space between pedigreed modern art (which we look at closely) and things that surround us everyday (which we don't give a second glance). He has described the lightboxes he's been making since the mid-1990s as "neither ordinary objects passing themselves off as art, nor works of art passing themselves off as everyday things." At first glance his Honeywell (1998) - a recent acquisition - could be a found object. It looks like exterior signage for the computer company. Slightly disarticulated, but fired up, the three lightboxes rest on the floor, as though about to be installed, or freshly deposed. The brandname - a one word haiku - suggests utopian abundance. In Everyday Minimal, Honeywell is accompanied by other works that draw on a minimalist aesthetic, but pollute or complicate it with everyday references. Alongside Speers, will be works by John Armleder, Hany Armanious, Mladen Bizumic, Stella Brennan, Julian Dashper, Mikala Dwyer, Rosalie Gascoigne, Richard Hamilton, Gavin Hipkins, John Nixon, John Reynolds, Ed Ruscha and Ian Scott.

- Date

- —

- Location

- Main Gallery

- Cost

- Free entry

Related Artworks

I.O.U.

coloured acrylic sheeting, synthetic rug, television

Chartwell Collection, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, 2001

Honeywell

vinyl on Perspex, fluorescent light tubes

Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, purchased 2003

Untitled

acrylic on canvas

Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, gift of the Patrons of the Auckland Art Gallery, 1996

The Gulf (Teen)

20 C-type prints (unique set)

Chartwell Collection, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, 2002

Big Yellow

roadwork reflector signs on plywood

Chartwell Collection, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, 1988

Five Tyres remoulded (portfolio)

relief cast, screenprints in black on mylar, sheet of text

Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, purchased, 1984

Various Small Fires

paper

Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, transferred from the E H McCormick Research Library, gift of the artist, 1978

Some Los Angeles Apartments

paper

Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, transferred from the E H McCormick Research Library, gift of the artist, 1978

Real Estate Opportunities

paper

Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, transferred from the E H McCormick Research Library, gift of the artist, 1978

Nine Swimming Pools

paper

Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, transferred from the E H McCormick Research Library, gift of the artist, 1978

Twentysix Gasoline Stations

paper

Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, transferred from the E H McCormick Research Library, gift of the artist, 1978

Thirtyfour Parking Lots

paper

Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, transferred from the E H McCormick Research Library, gift of the artist, 1978

Hauturu Doc (with soundtrack 'Adagio Under My Thumb' by the Rolling Stones)

computer animation transferred to video, single channel, standard definition (SD), 4:3, black and white, stereo sound

Chartwell Collection, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, 2003