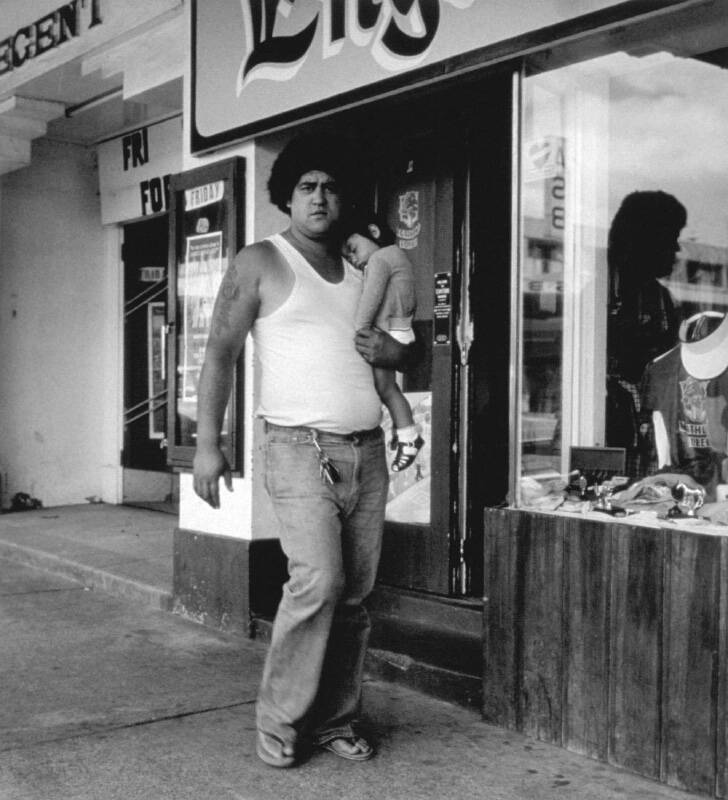

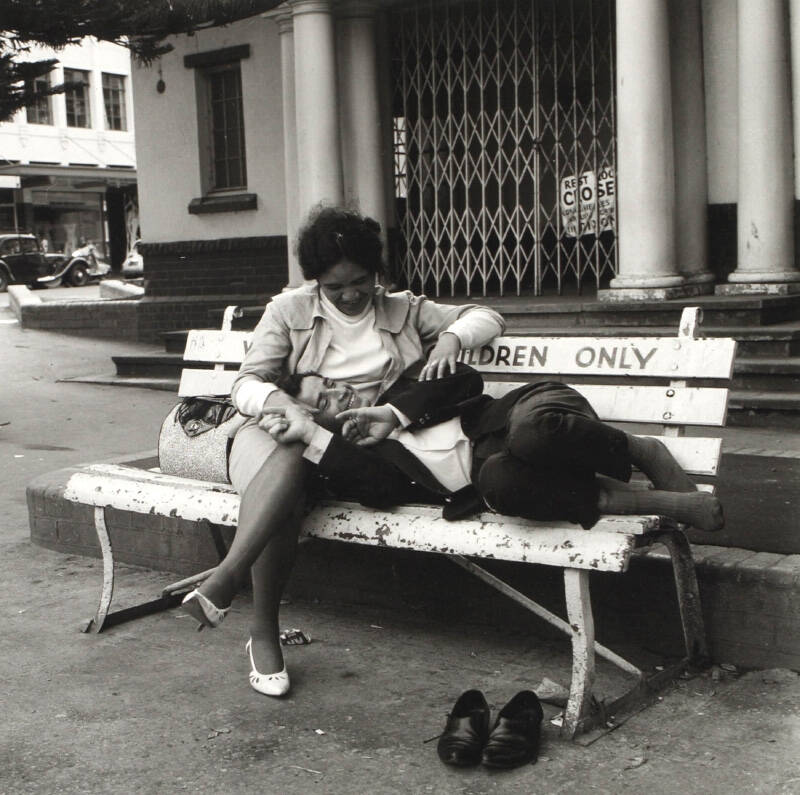

Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki was saddened to learn of the recent passing of New Zealand photographer Ans Westra (1936–2023). The Gallery has 59 of her photographs in its collection; the earliest. from 1960, shows a couple snuggling on a street bench in Wellington. Westra belonged to a generation of social documentary photographers – including figures like Gil Hanly, John Miller (Ngāpuhi), Robin Morrison, and John B Turner – who introduced new ways of seeing New Zealand in the 1960s and 70s and in doing so elevated photography to the realm of fine art. In the suburbs, at protests, or on the road, the documentarians were interested in peoples’ everyday lives and in recording social change. This emergent mode of practice was nurtured by PhotoForum Inc., an organisation which supported artists to develop more personal photographic sensibilities through the ethos of ‘learning how to see’.

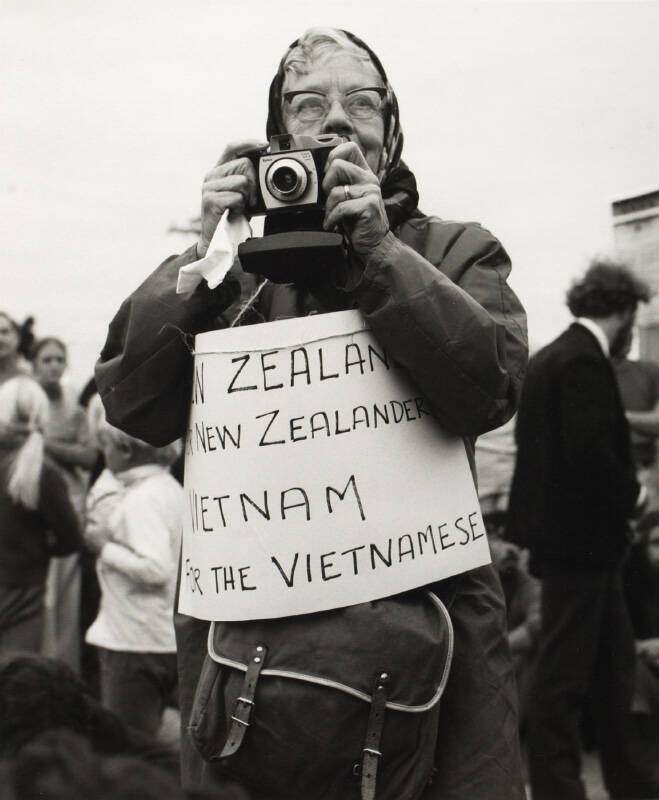

Westra’s work was included in the groundbreaking The Active Eye (1975), one of the first exhibitions to critically engage with this new photography and which toured to art galleries throughout New Zealand. Three of her images were reproduced in the exhibition catalogue: a photograph of young men in Albert Park, people relaxing over pints at the Trentham Racecourse, and a man surveying stock at a saleyard in Invercargill. These images reflected Westra’s eagerness to travel the length and breadth of the country to get to know it. She spoke of photography as her visual diary, but her approach was also shaped by post-war humanist photography, like that celebrated in New York’s controversial Museum of Modern Art exhibition, The Family of Man, which Westra saw when it toured to the Stedelijk Museum in 1956.